(Images: Spin Seattle)

Is there room for another bike share system in Portland?

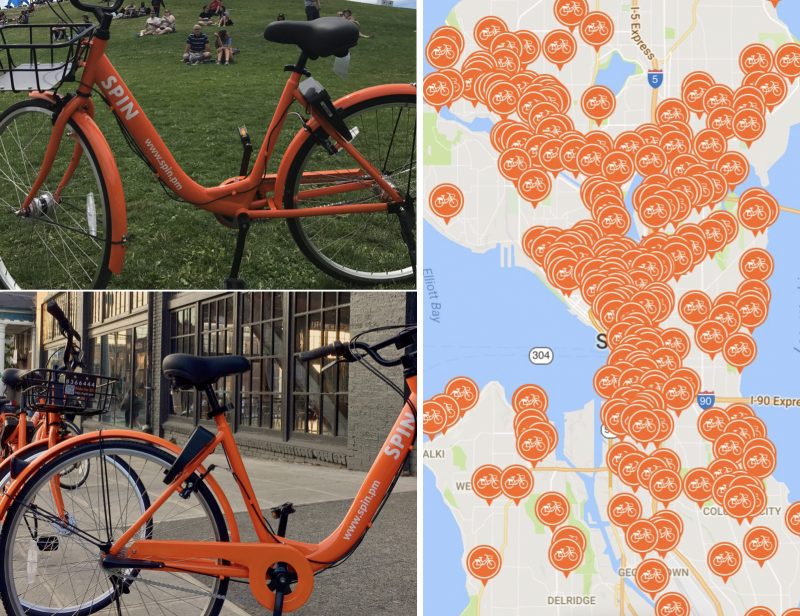

A company called Spin that just launched in Seattle thinks so. Spin is a start-up fueled by venture capitalists and founded by Derrick Ko, a former product manager at Lyft who’s now Spin’s CEO.

In his first major play, Ko plopped 500 bikes on Seattle streets last week. So far the results have exceeded expectations. Seattle Bike Blog reports that people took over 5,000 trips on the bikes in the first week and rave reviews are pouring in on social media.

With bad memories from their failed first attempt fading quickly, Seattleites have embraced the latest bike share trend: a stationless (a.k.a. dockless) system run by a private company that offers cheap rides and a citywide service area with no strings attached. All it takes to unlock a Spin bike (or a LimeBike, which also just launched in Seattle) is an app and a buck. There are no pricing plans, no memberships, and no stations to find. Just find a bike, tap a few buttons on your phone, and get rolling. When you’re done just close the rear lock and leave the bike wherever you want. Spin charges $1 for every half hour you’re in the saddle (Biketown’s cheapest fare is $2.50).

Tom Fucoloro with Seattle Bike Blog likes what he sees. “If these companies succeed how they think they will,” Fucoloro wrote Tuesday, “we’re on the verge of a major non-motorized transportation revolution in our city.” He also issued a warning to other cities: “Any traditional bike share system that hasn’t built out a very dense network of stations should be working hard right now to figure out how to compete. Outside maybe a few extremely dense and tourist-heavy cities like New York, that old… pass pricing model is going to get crushed by $1 rides. Maybe even giants like NYC’s CitiBike are vulnerable.”

Is Biketown vulnerable to the stationless revolution?

Unlike New York City’s CitiBike system, Biketown uses “smart bikes” that have all their technology on-board instead of in large expensive stations. This gives Biketown distinct advantages over kiosk-dependent systems, primarily because the bikes and stations are cheaper and easier to move around. It’s a decentralized model that Biketown Program Manager Steve Hoyt-McBeth says should give stationless bike share companies like Spin pause.

At a PBOT bike advisory committee meeting in May, Hoyt-McBeth acknowledged stationless systems are likely on their way but said Biketown’s use of smart bikes, “makes our market a little less attractive to those competitors.”

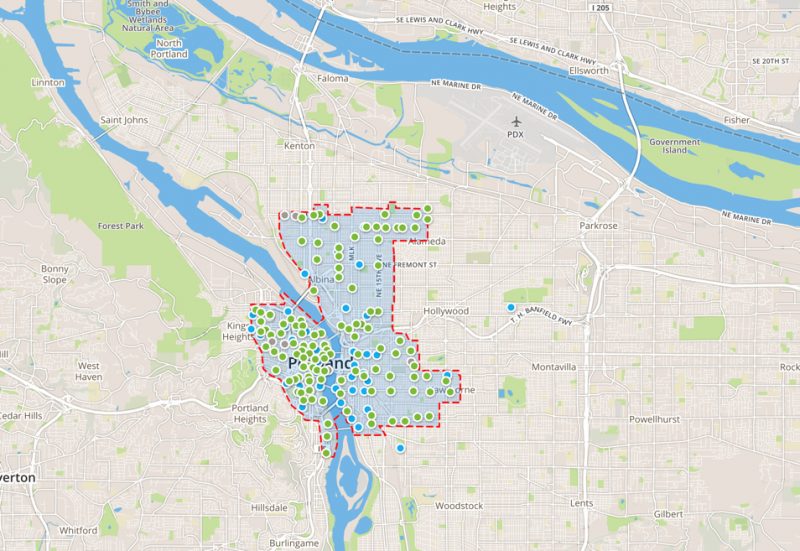

But “those competitors” have distinct advantages of their own. Beyond its less expensive $1 rides, Biketown doesn’t offer quite as much freedom and convenience to users as the leave-it-anywhere-you-want model does. Biketown bikes must be returned to a station or to a designated bike rack to avoid a $2 fee. Park a Biketown bike outside the service area — which still comes nowhere near reaching the entire city — and you’ll be charged $20.

Advertisement

Asked how Biketown would compete with stationless systems, PBOT Communications Director John Brady said, “We feel Biketown provides the best of both worlds. Our 100-plus stations make finding a bike throughout the service area reliable and easy, while Biketown’s smart-bike technology makes it convenient to park at any of our 4,000 bike racks.” Brady also stood up for Biketown’s supplier Social Bicycles (SoBi), which he called, “North America’s original dockless bike share system.” “We began talking with SoBi in 2012 and utilizing their technology has been on our plans long before dockless bike share emerged,” he said.

Brady pointed to PBOT’s recent creation of “super hub zones” (areas where you can park at any rack without incurring the $2 fee) and expansion into north and northeast Portland by using existing bike parking and without adding more bikes or stations to the system as, “examples of how flexibility and the potential for innovation are built into the very DNA of our system.”

We got a clue about how PBOT will respond to stationless bike share two years ago when Spinlister threatened to launch a system here. Hoyt-McBeth told us at the time that his concern would be that PBOT would end up maintaining the fleet. “If you’re going to operate a bike share system in the public realm, then we want to make sure those bikes are cared for,” he said. “We don’t want to be in a situation where we’re the de-facto rebalancing instrument through our abandoned bike [telephone] line… We just want to know how they’re going to make sure their bikes don’t get abandoned.”

PBOT and Motivate (Biketown’s operator) could make their bikes even more flexible by allowing them to be parked anywhere, but so far that’s not in the plans. Highly visible stations serve a purpose for Biketown that transcends utility. Because the system is reliant on sponsorship dollars, stations are important marketing tools. It’s unlikely Nike would have put $10 million on the table without also getting 100 shoe-box colored pieces of prime urban real estate. Stations also educate users while providing a strong visual cue that assuages doubts about how the system works.

Given the strengths and weaknesses of both systems, perhaps they can coexist.

A complement? Or a competitor?

“Station-based systems are great… But we look at them like the bus or the train in a city… We are more of a taxi.”

— Derrick Ko, Spin CEO

In an interview yesterday, Spin’s Ko told me he sees his system more as a complement to Biketown, not a competitor.

He gave kudos to our “fantastic system” and said Social Bicycles “did a great job.” But Ko also pointed out that Biketown’s primary use-case is still centered around kiosks. That lack of freedom to place bikes wherever users want leads to less coverage and ultimately fewer rides. “We’ve seen over 5,000 in one week… We’re reaching neighborhoods Pronto didn’t cover,” Ko said, “That’s really what stationless gives you. That coverage to provide a new transportation option to people in all neighborhoods.”

By comparison, Biketown averaged about 14,500 rides per week when it launched. But that was with twice as many bikes (1,000 versus Spin’s 500) and after years of planning.

Portland spent over nine years trying to make bike share happen before Biketown finally launched in 2016. The road that led to Nike’s $10 million sponsorship deal began in 2013. In stark contrast, Ko told us he started talks with the City of Seattle in April of this year. Four months later he had 500 bikes on the ground and another 500 are coming next week.

The quick launch and adoption by users reminds me of when Uber and Lyft drivers first hit the streets. That’s how Ko sees it too. “Station-based systems are great, they’ve helped form the foundation by changing a lot of attitudes about bikes being a legitimate public transportation option. But we look at them like the bus or the train in a city. They get you to drop-off points. We are more of a taxi, or like Uber or Lyft getting you from point-to-point.”

“Both systems are coexisting in the vehicular world and there’s no reason two systems can’t exist in the world of alternative transportation,” he added.

Room for more?

Even if it made sense from a practical standpoint to have more than one bike share system at the same time, the arrangement would have to get the blessing of the City of Portland. Unlike Uber — or the aggressive stationless systems flooding China like Ofo and Mobike — Ko says Spin prefers to work closely with local governments before launching. The City of Seattle and Spin hashed out a permit agreement before any bikes hit the streets. The same would have to happen in Portland.

PBOT’s Brady said a private bike share company would have to follow existing regulations for operating in the right-of-way. And, he added, “Dockless bike share systems would require additional regulations to be developed.”

And Nike’s presence could also make life more difficult for a company like Spin. While only the title sponsor of Biketown, Nike will want to protect its investment and PBOT would be loathe to ruffle their feathers by welcoming another bike share provider (especially one that uses orange bikes!).

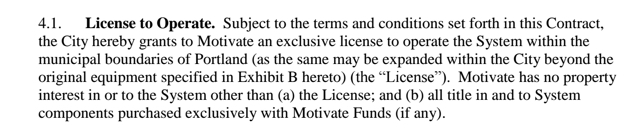

As for exclusivity, PBOT’s contract doesn’t appear to give Motivate Inc. (Biketown’s operator) an exclusive right to operate bike rental systems in Portland. According to our interpretation, the contract only gives them the exclusive license to operate Biketown. And while PBOT says they aren’t looking for any more bike share partners at the moment, they’re also not dismissing the idea.

What would PBOT say if Spin were to inquire? “Without seeing a specific proposal,” Brady said via email when I asked him that question yesterday, “it’s really too soon to say. As with any new transportation option, we would consider whether a proposed system met our larger policy goals…”

Then Brady followed up that email with a phone call to add this. “We’re very happy with Biketown. We’re not actively considering another system.”

So far Spin hasn’t made any formal inquiries. Ko says, “We are still looking at it and trying to figure out how best we can fit into the Portland scene.” “We’d love to come to Portland,” he added, “I think it’d be an amazing fit.”

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

BikePortland is supported by the community (that means you!). Please become a subscriber or an advertiser today.