(Photos: Travel Oregon)

Something big is about to happen for off-road cycling in Oregon.

On March 23rd the nonprofit Oregon Timber Trail Association will do a soft-release of their Oregon Timber Trail, an experience its creators promise will be, “North America’s premiere long-distance mountain biking route” and a “world-class bikepacking destination.”

That might sound boastful, but once you learn more about this project and the people behind it, it’s easy to see why they’re so confident.

“There’s a big difference between us drawing a line on a map and having the Forest Service draw a line on their map.”

— Harry Dalgaard, Travel Oregon

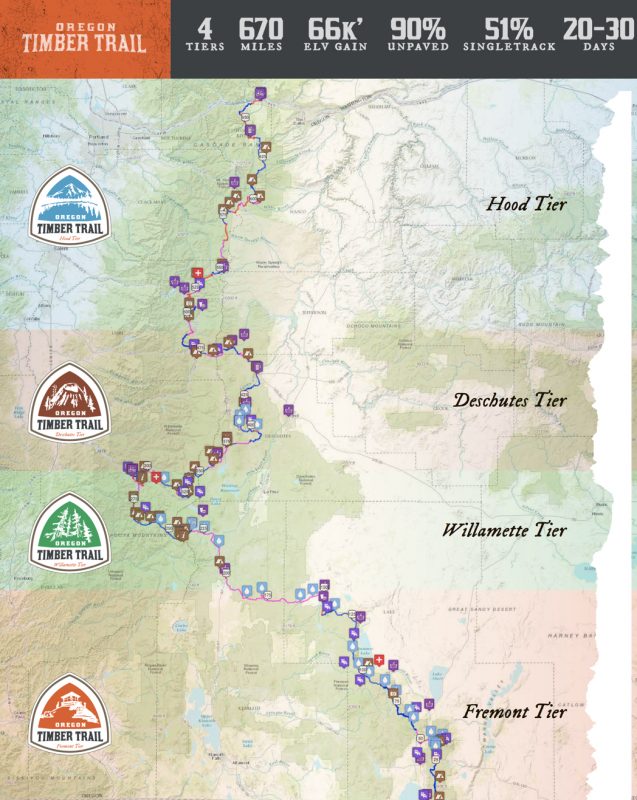

Inspired by Pacific Crest Trail, the Oregon Timber Trail (OTT) winds 670 miles from the California border to the Columbia River Gorge. Its lucky riders will roll through pristine forests (without clear-cuts!), old wagon roads, volcanic deposits, remote hot springs, high deserts and roaring rivers.

What makes the OTT special isn’t just that bikes are allowed to ride on it (unlike the Pacific Crest Trail), but that it was created specifically for cycling. 90 percent of the route is unpaved and a whopping 55 percent — around 340 miles — is singletrack.

Development of the trail began in 2015 when Travel Oregon hired a trail planning expert to create the alignment and concept. Harry Dalgaard, a tourism program manager with Travel Oregon, shared with me during an interview in October that his agency launched the project in response to feedback from the Oregon Bicycle Tourism Partnership, a stakeholder group made up of business owners, land managers, and advocates. “They told us loud and clear that Oregon needed more ‘world-class’ cycling experiences.”

What makes something “world-class”? Think of a trail that will garner international media coverage and entice people from all over the world to spend precious vacation time just to give it a try.

(Graphic: Limberlost via Oregon Timber Trail report (PDF))

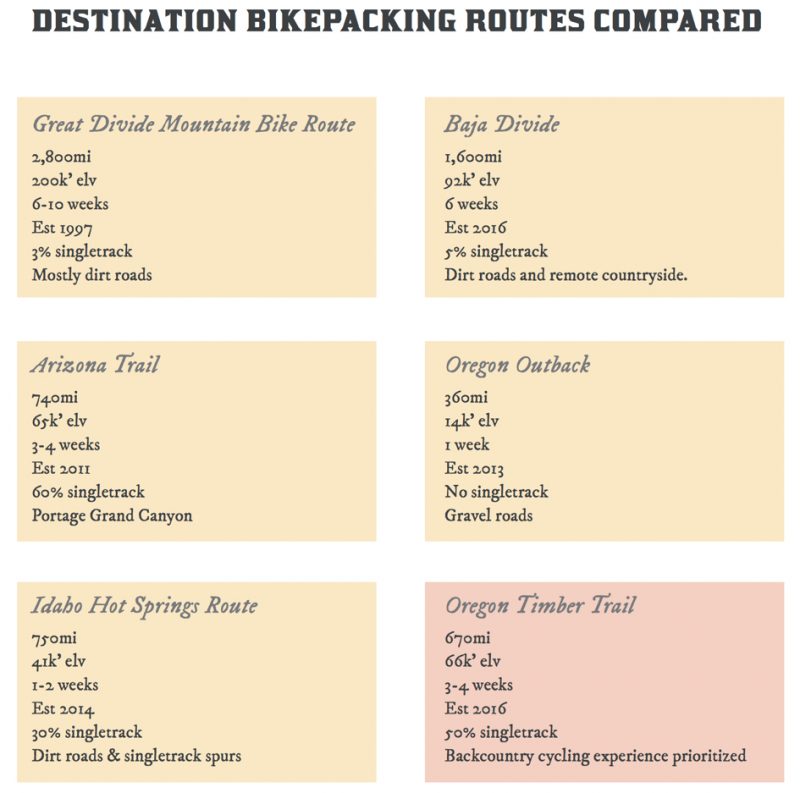

To make it a reality, Travel Oregon enlisted the expertise of Chris Bernhardt in spring of 2015. Bernhardt is a renown trail planner who previously worked for the International Mountain Bicycling Association and Alta Planning and Design and is now a private consultant. As a starting point Dalgaard and Bernhardt looked at trail systems in the Swiss Alps and New Zealand, existing bikepacking destination trails across North America, and hut-to-hut systems like the San Juan Huts in Colorado.

The goal was ambitious: Create a Pacific Crest Trail-like mountain biking experience that would display the splendor of Oregon’s natural wonders, boost Oregon’s $400 million annual bicycle tourism economy, and be accessible by a wide range of riders.

As Bernhardt hammered out trail alignment details (and came up with the name, a nod to Oregon’s heritage), Dalgaard added another key player to the team: Gabriel Tiller. Tiller is the graphic artist and adventure journalist who founded Limberlost, an off-road exploration and touring company. Tiller helped shape the visual narrative of the trail and he served as first lieutenant with Dalgaard to make the project a reality.

Tiller and Dalgaard say they both committed to “the long game” early in the planning process. Instead of simply plotting a route with an online mapping tool and then publicizing it through standard channels — they wanted to enshrine the trail at the highest levels of legitimacy.

“It’s easy to release a route,” Tiller said, “But we don’t want this to be like the Oregon Outback and fizzle out after two years.” Tiller’s reference’s was to the unsanctioned off-road ride and route through central Oregon that got so popular its second year it attracted a bit of unfortunate controversy.

Advertisement

Once Bernhardt analyzed the route and hammered out an alignment, Dalgaard took the concept to the United States Forest Service office in Portland. They encouraged him to run the idea by local trail user groups and land managers along the route. Since 95 percent of the route’s mileage is on USFS land, Dalgaard took the advice to heart.

(Photo: Travel Oregon)

Tiller and Dalgaard embarked on an 11-month outreach mission, traveling to towns large and small along the alignment in an effort to solicit feedback and — hopefully — support. They met with over 40 trail user groups, made 16 presentations and held eight, two-day planning charrettes.

The alignment goes through existing trails, roads and other public right-of-way where bicycles are already legally permitted. Even so, clear benefits would come from the hard work of asking for endorsements from the USFS and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) staff in each of the four National Forests the trail passes through.

“To have the Forest Service integrate this into their management plans gives the trail more institutionalization,” Dalgaard said, “There’s a big difference between us drawing a line on a map and having the Forest Service draw a line on their map.”

In addition to institutional support, local land managers and trail users gave Dalgaard and Tiller valuable insights about the route itself. The outreach effort proved to be a key step for another important reason: it gave the Travel Oregon team a chance to educate people about bikepacking, a relatively new activity many current trail users and forest stakeholders might not have experience with. To many people, “mountain biking” conjures images of full-faced helmets and aggressive, high-speed riding — while bikepacking is more akin to hiking with wheels.

The ability to explore Oregon’s history while on the trail is one of the key attractions of the route. At an explorers pace, you should be able to complete the entire route in just over two weeks (less than 40 miles a day). But Tiller and Dalgaard don’t expect everyone to attempt the full trail in one bite. They’ve split the route into four distinct “tiers” ranging from 130 to 200 miles — each one with a distinctive character based on its natural features.

And for those who want a bit more luxury, trail backers want to refurbish existing USFS structures into overnight shelters and coordinate with existing private cabin and lodge owners in order to offer a true “hut-to-hut” option. The newly opened Suttle Lodge near Sisters, for instance, is already planning a bike wash station and repair shop.

There are more plans for the future. That’s where new nonprofit Oregon Timber Trail Association will step in to complete the project’s next phases. Those include work on the overnight shelters, creation of a printed map and guidebook, new signage along the route, educational kiosks, trailheads, and building new segments of singletrack.

With the support from land managers and Travel Oregon, and the branding flair/street-cred Tiller brings to the project, the Oregon Timber Trail could become the most iconic cycling attraction in the state — or maybe even the entire continent.

Time to start making plans for summer.

Oregon Timber Trail Launch Party

March 23rd, 6-9:00 pm at Base Camp Brewing (930 SE Oak St)

“We’ll talk about where it came from, where it’s going, and what it’s like now. Meet the Oregon Timber Trail Association and find out how you can get involved and make Oregon trails better for everyone.”

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

BikePortland is supported by the community (that means you!). Please become a subscriber or make a donation today.