Part of NW Portland Week.

Portland’s “huge population boom” and “explosive growth” have driven such a painful housing shortage that it’s not uncommon these days to hear Portlanders wish the city would stop creating so many jobs.

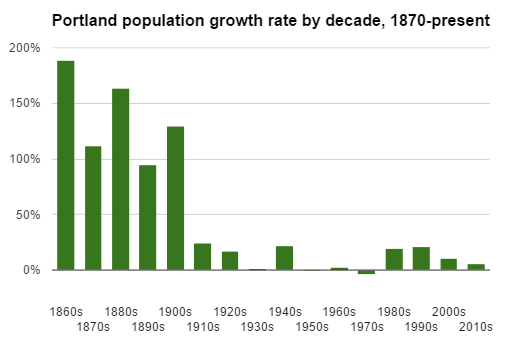

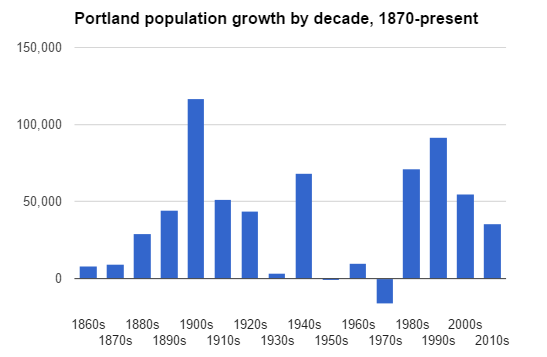

Since 2008, the city’s population growth rate has been about 9,000 net new residents per year, or 1.5 percent.

But when many of the buildings that continue to define northwest Portland were built, Portland’s population was growing by 7 percent every year for years on end. In the decade of the 1900s, the city that started at 90,000 residents added 11,679 new ones every year on average.

How could it happen? With so many migrants pouring into the aftermath of northwest Portland’s hugely successful Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in 1905, how could the city have possibly kept housing costs low enough to keep wages manageable for the host of new employers popping up? How did the city avoid cultural collapse?

Portland’s situation wasn’t unique. Seattle grew even faster in the same decade, and Los Angeles faster still. San Francisco’s similar boom came in the 1870s. For St. Louis it was the 1850s; for Philadelphia the 1860s; for Chicago the 1890s; for Detroit the 1910s.

How did cities survive population booms four or five times larger than Portland is going through today?

And why, somewhere around 1920, did U.S. cities never see population booms again — even in an age of deep geographic inequality that is watching smaller cities like Urbana, Illinois continue to shed jobs while some bigger ones, including Portland, add them hand over fist?

You can see the answer any time you ride a bike through northwest Portland. Growing cities built and built and built — because until 1920 or so, there were no laws that said you couldn’t.

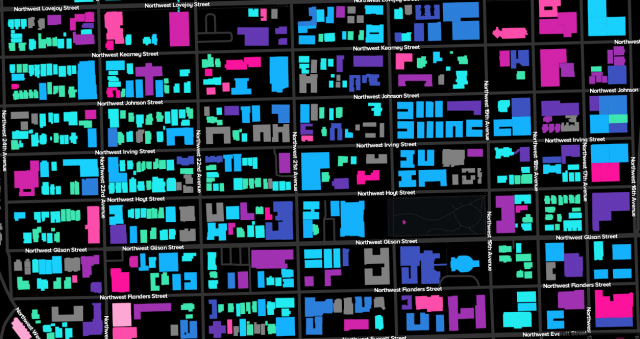

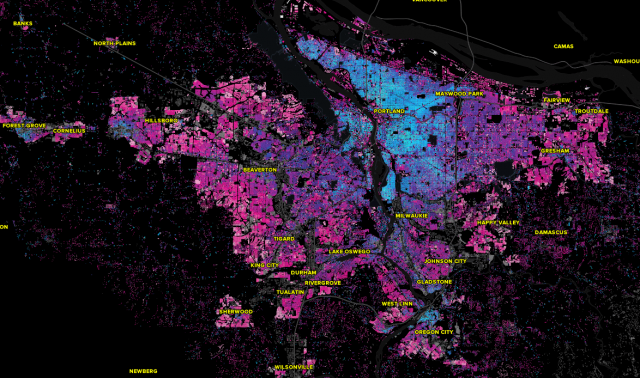

There’s no single image that explains Portland’s history at a glance better than Justin Palmer’s amazing Age of a City map, which color-codes almost every building on the Oregon side of the metro area by the decade of its construction.

(Image: Justin Palmer)

Zoom into northwest Portland and you can see the history, block by block, of how Portland survived its explosive 1900s:

Portland approved its first zoning laws in 1918 and expanded them by popular vote in 1924, limiting basic construction to four stories and maximum height to 15 stories; it was approximately the same year that local streetcar usage started its long decline. In 1945, lawns and driveways became mandatory in most of the city as minimum lot sizes were set at 5,000 square feet for single-family zones; in 1959, duplexes and internal home divisions were banned from single-family zones.

Nobody seems to be sure when mandatory garages and other minimum parking requirements arrived; Tony Jordan of Portland Shoupistas said city staff told him it was probably the 1950s.

Advertisement

None of this is to say that Portland’s boom decades were a golden age. The city had as many or more problems then. And it is not to say that market-priced housing can ever address the separate and huge problem of poverty. It can’t.

But the 1900s are proof positive that market-priced housing, if there’s enough of it, can be perfectly capable of controlling housing costs for those of us who aren’t currently poor.

And today, spending time in the neighborhoods Portlanders built in the 1900s, like much of northwest Portland, doesn’t just mean seeing buildings that were needed to prevent spiraling rents or enable job growth. It means enjoying yourself. It means spending time in a place that is quite nice.

Last year, former Metro councilor and former northwest Portlander Robert Liberty wrote a love letter to Nob Hill called “My Illegal Neighborhood.”

Typical city zoning makes it illegal to build or operate a warehouse or a light industrial use next to homes and a grocery store. The separation of industrial and commercial uses from residential uses was the very foundation of zoning a century ago.

It is illegal in most cities to build apartment buildings without providing one or more parking spaces for every apartment. The same would be true of grocery stores or office buildings. The neighborhood’s grocery store has fewer than 20 parking spaces.

The street in my old neighborhood does not meet more current design requirements, because it is considered inappropriate to design a street so that car cannot pass each other at any time or location. The street is 27 feet wide, curb to curb. That includes parallel parking on both sides, leaving a travel lane about 12 feet wide. That violates the standards for a local road recommended by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

In most cities, you cannot operate a business out of your home if you have employees or customers arriving from other locations.

In too many places, it is effectively illegal to build subsidized housing for families of modest means. Even when it might be legal, local officials can interpret nebulous phrases like “preserve neighborhood character” or complex regulations in way that such housing is never approved.

A senior center, even though it is not a business, would be treated like a commercial use that cannot be allowed next to single family homes.

The elementary school would probably be illegal too because the school property would be too small to meet many states’ standards. The school is located on about 9.8 acres but many of those acres are occupied by a park open to the public at all times. The school, which has 685 students, would require a site of 11.85 acres in California, Texas and Connecticut, 15 acres in New Mexico and 18-20 acres in suburban Pennsylvania.

And then there is the absence of parking places; according to Virginia’s 2010 school design standards, the school should provide parking for all the staff, visitors and about a third of the students. (Apparently the legal driving age in Virginia is much younger than in Oregon.) …

Does that mean do away with all regulations? No. But it does mean that we need to stop assuming that everyone wants to, or can afford to, live in a big house on a big lot in a residential-only neighborhood. We shouldn’t be making it illegal to build the kind of neighborhoods, like mine, that are increasingly popular and in short supply.

Portland is in the middle of an election season in which no subject is hotter than the upward spiral of market-rate rents. The problem has the city in a constant roil. Policy wonks are scouring the planet for cities with tools that can prevent rapid population growth from becoming a disaster for market-rate housing.

Northwest Portlanders are lucky. The model everyone is searching for is their own history, and it’s standing right in front of them.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today..