In 2013, when the Portland City Council began requiring most new apartment buildings of 30 or more units to include on-site parking garages, housing watchdogs warned that this would drive up the prices of newly built apartments.

Because the city still lets anyone park for free on public streets, they predicted, landlords wouldn’t be able to charge car owners for the actual cost of building parking spaces, which can come to $100 to $200 per month. So the cost of the garages would be built into the price of every new bedroom instead, further skewing new construction toward luxury units.

Three years later, rough data suggests that this could be exactly what happened.

To be sure, this would be only one factor in many that have driven up Portland housing costs. Rents have been rising faster among old units than new ones. But as the city council nears what looks like a tight vote on whether to impose similar mandatory-parking rules in Northwest Portland, affordable-density advocates warn that the story could repeat itself.

Portland affordability advocate Brian Cefola got in touch with us last month to share the numbers he’d crunched using local building permit data published by the U.S. Census.

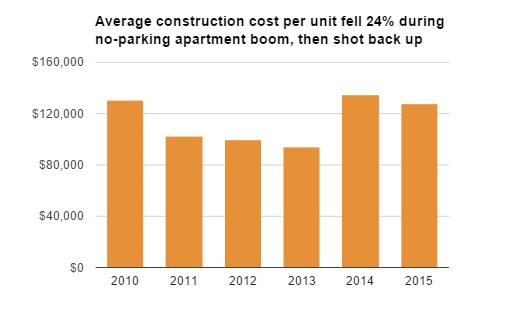

It turned out, Cefola discovered, that the average cost of building a home in a Portland multi-family building dropped 24 percent between 2011, when Portland’s first wave of no-parking apartments began to open, and 2013, when the new city rule took effect.

At that point, the average price returned to its previous levels.

The housing boom and collapse surely play a role in this data, though the exact role isn’t obvious. The international recession and subsequent job collapse began in late 2008; job losses peaked in January 2009. By 2010 — before the price drop Cefola identified — Portland’s economy had become relatively stronger than the national economy, and migration to Portland was accelerating further.

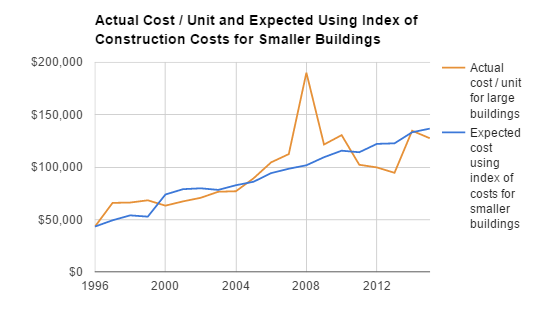

In an effort to correct for changes in labor and other construction costs, Cefola (an insurance analyst in his day job) also crunched the numbers further. Using the cost of building homes in small buildings (one to four units), he created an index of what you’d “expect” units in large buildings to cost if the rules for large buildings hadn’t changed.

That adjusted measure revealed a large, brief spike in per-unit construction costs in 2008, when the recession hit.

Something else it revealed: during the 2011-2013 no-parking boom, the average new Portland apartment cost 17 percent less to build than would have been “expected.” Then it returned to normal.

Data too noisy to draw firm conclusions from, experts agree

Even local experts who oppose parking minimums cautioned that Cefola’s numbers aren’t precise enough to draw solid conclusions from.

“I think it’s really, really hard to draw any strong inferences about the role of parking requirements on building costs based on such aggregate data,” said Joe Cortright, a Portland-based economist who often writes for City Observatory about the unintended costs of overbuilding parking. “The average per unit costs are highly sensitive to what we call composition effects: sometimes developers build expensive stuff in the Pearl (larger units, nicer finishes) and sometimes its spartan studios. So the per unit cost can fluctuate depending on the mix (composition) of the units being built in any particular year. I think that’s clearly what’s going on in 2008–where you see a big spike in the average cost per unit. When the market went south, the only thing that was moving forward, apparently, was pretty high end stuff.”

“This is, alas, only circumstantial evidence,” Cortright wrote.

Chris Smith, a Northwest Portland resident who this month led a successful vote by the Planning and Sustainability Commission against new parking minimums, agreed.

“I would guess that a variety of construction cost factors rising would make it hard to point to parking specifically as a cost driver in the data set we have,” he said.

Advertisement

Cefola doesn’t argue otherwise.

“It’s an indication, and I think indications can be wrong,” he said.

But Cefola, who serves as president of the Grant Park Neighborhood Association in his spare time, said the data lines up with logic.

“Many people warned that it would have an impact on affordability and the kind of construction that would be put up,” Cefola said. “It added this fixed cost per unit. I think people, myself included, warned that it would incentivize larger units, higher-end units.”

(Image: TVA Architects)

There might be no better test case in the city than a project (still unfinished) called Overlook Park Apartments. That project was designed with no parking before the code change, then redesigned with parking after the code change.

The second plan for the building had 17 parking spaces, fewer housing units and higher target rents.

Cefola said he thinks his circumstantial evidence is enough reason for professionals at the city to dig deeper.

“I think there’s this question out there that the city really ought to be answering,” Cefola said. “Given the fact that they say there’s a state of emergency on housing, how come they haven’t made any attempt to assess the parking policy they put in four years ago?”

Interested in parking reform? Come to BikePortland’s wonk night Tuesday to help smarter parking rules build a better low-car city.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without subscribers. It’s just $10 per month and you can sign up in a few minutes.

The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here.