(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

It’s 8:10 a.m. on Friday morning and the most controversial man in the Richmond neighborhood has just finished reading the funnies.

The doors of the shops he passes open directly onto the sidewalk. They have to; that’s what it says in the code that Klotz helped the city write.

“They still print it every day, they just refuse to deliver it,” Doug Klotz says.

He says it in the same way he says a lot of things: amused, annoyed and apropos of nothing.

Then he folds shut The Oregonian’s living section, eats the last bite of his sausage and brushes aside his flop of gray hair.

In five minutes Klotz, 64, will be rolling his bike down the driveway of the creaky 1905 house that he and his wife, Marsha Hanchrow, live in and have been very gradually renovating since 1999. He’ll pass his green 1952 Chevy, its battery hooked to a trickle charger to stop it from going dead between uses. Then he’ll head to work.

On the way, he’ll pass the three-story building at Hawthorne and 34th that would almost certainly be a McDonald’s drive-through today if the plan to build it hadn’t run into trouble with the Richmond Neighborhood Association, whose land use committee Klotz was chairing back in 2001.

Today, the row of mixed-use storefronts and condos the developer finally agreed to build instead is full of boutique clothing shops, the western anchor of a commercial district that runs east to 50th Avenue.

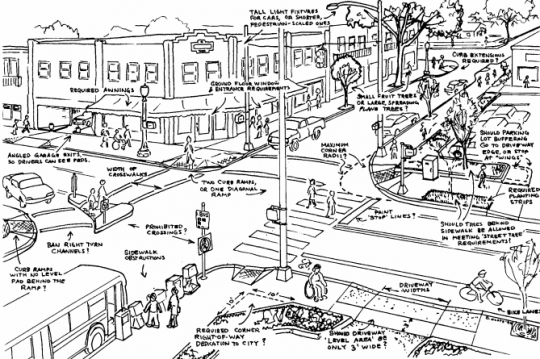

Like almost every Portland storefront built facing a transit line since 1991, the doors of the clothing shops open directly onto the sidewalk, not a parking garage or surface lot. They have to; that’s what it says in the code that Klotz helped the city write, a project that at one point featured a sketch by Klotz on its cover.

Klotz’s commute takes him west down Madison. It’s been his route to work since 2003, when he switched from bus to bike to save money.

Madison’s sidewalks, built around 1905 with grassy buffers between them and the curb, look a lot like sidewalks in new subdivisions across the country. That’s because the 1998 Portland Pedestrian Design Guide that Klotz helped create, which ended up being a model for many U.S. cities, specified that instead of running right along the curb, every new sidewalk should have a buffer of at least two feet.

“Like the ones in the older neighborhoods,” Klotz says.

Klotz crosses Grand Avenue and passes into the Central Eastside Industrial District.

“I’ll need to change clothes,” he mentions. “Into my uniform.”

Then Klotz pulls up to Wink’s Hardware, rolls his bike inside, and starts his work day.

Change agent with a day job

How did Doug Klotz get into this pickle?

How did a hardware store clerk with a film degree become the subject of duelling mass email campaigns that rallied 252 people to a Sept. 14 vote over whether to recall him from the board of the neighborhood association where he’s served since 1993 — and how did Klotz, despite more than 150 people who showed up entirely to vote him out, remain in office by a single vote?

Officially, the issue is that Klotz violated the Richmond Neighborhood Association’s code of ethics when he described several board members in an email to biking advocates as “less than bike friendly.”

It’s very likely true that this was a violation of the RNA’s rules, which forbid RNA board members from making “public statements representing the views of the organization” without permission from the board. That was the conclusion last month of a special investigative committee.

But the truth is that hundreds of people did not pack a meeting to vote for or against Klotz because he was trash-talking other neighborhood board members.

They showed up because Klotz is so good at advocating for his beliefs that his decades of volunteer work have, gradually, added up to actual changes.

Big changes.

‘Things were not getting built’

When Michele Wong was growing up off Division Street, friends who lived west of the Willamette River told her they were scared to visit the east side.

“It wasn’t that nice of a neighborhood,” said Wong, whose parents had bought land along Division in the 1960s.

People called her father a “slumlord,” she said in an interview Thursday. When she started getting into retail development, some people thought she was “a front for him.”

That was what happened when Wong first showed up at the Richmond Neighborhood Association in the late 1990s, asking for permission to redevelop a corner lot at Division and 30th to a ground-floor cafe with two apartments above.

“Things were not getting built and the impediment seemed to be the parking requirements.”

— Doug Klotz

The city approved her plan on the condition that she rent two off-street parking spaces from someone else nearby. But nobody would lease them to her.

“They thought I was putting in a strip bar for some reason,” Wong said. “We kind of abandoned the project. … And ended up doing a vacant lot for a long time.”

Vacant lots weren’t what Klotz and other members of the Richmond Neighborhood Association were hoping for, either. They were eager for nice places to eat and socialize nearby.

“Things were not getting built and the impediment seemed to be the parking requirements,” Klotz said.

So the RNA supported a city request to get rid of minimum parking requirements within 500 feet of a frequent bus line.

In 2005, Wong tried her plan again. This time, it went through.

“They changed the whole parking issue, so we didn’t need parking any more,” she said.

Caffe Pallino opened there in 2007, the first of a series of new retail shops on the block that now faces the Bollywood Theater restaurant and a painfully quirky mixed-use remodel called D Street Village. The shop recently changed hands and now houses American Local, one of Division Street’s latest award-winning restaurants.

A transforming city

Like most people who’ve owned houses near Hawthorne and Division for more than a few years, Klotz and Hanchrow don’t make enough money to buy into their neighborhood today.

Is that because of the new buildings that Klotz helped make possible?

Klotz said Richmond was already getting expensive before people like Wong (who sold Caffe Pallino and now runs Old School Coffee on 82nd Avenue) started building shops and opening restaurants.

“The price has gone way up because people want to live in the inner city,” Klotz says. “We’re not allowing the type of building that would solve that problem.”

If the city focused less on saving room for cars, Klotz argues, more projects could be built, and Portland’s housing supply could better keep pace with the 10,000 or so net new residents that have shown up almost every year since 1987 — which also happens to be the year Klotz arrived.

But Klotz wasn’t always a fan of density. He only started supporting bigger buildings on main streets because he gradually decided that they were the best way to support something else he believed in deeply: walking.

‘Unless you have the density, you’re not going to get a walkable neighborhood’

(Photo courtesy Ellen Vanderslice)

You’ve heard of the advocacy group Oregon Walks? It was Klotz’s idea. Seven Portlanders founded it in his living room in 1991.

Or maybe you’ve heard of the crosswalk enforcements the City of Portland conducts every few months. The city got the idea from Klotz and his Oregon Walks co-founder Ellen Vanderslice, who in the early 1990s started walking back and forth across crosswalks as do-it-yourself street demonstrations.

Over time, Klotz’s affection for walking and for riding good bus lines — like the 14, on which he and Hanchrow met — became an affection for neighborhoods that had enough density to bring storefronts and good bus lines within walking distance.

“I decided maybe 7 or 8 years ago that unless you have the density, you’re not going to get a walkable neighborhood,” Klotz said. “The customer base supports businesses to be there.”

Vanderslice, who like Klotz trained as an architect but who unlike Klotz finished her degree, was hired off the board of Oregon Walks to write Portland’s Pedestrian Design Guide, the one that became widely imitated. She retired in 2012 from a celebrated career at the city, during which she sometimes came to envy her friend’s job at the hardware store.

“It’s an interesting thing: in keeping his professional life really separate,” she said, “he can say whatever he wants and he can really speak the truth.”

“In comparison, look at me — I got tired and I quit!” she said. “I got burned out.”

‘He is sort of an odd duck’

(Photo courtesy Ellen Vanderslice)

Klotz now calls himself “semi-retired.” He’s down to two days a week at Wink’s: Mondays and Fridays from 9 to 5:30.

His co-worker Kaiya Ketterman said Klotz often talks to other shop employees about issues around town. She said those conversations usually start with him muttering to himself about an email he’s just received.

“Everybody always says that he should be mayor,” she said.

“So many of our really dedicated, wonderful, brilliant citizen volunteers are annoying.”

— Ellen Vanderslice, co-founder, Oregon Walks

Klotz hoped that by downshifting at the hardware store, he’d be able to devote more time to finally fixing up his house.

“But all these other things expand to fill that space,” he said. “Forestry Commission, Planning Commission. … I can go to design review hearings! I can go to preapp conferences!”

Klotz doesn’t sit on those commissions. But he’s learned that if he attends, people who are on them will listen to him.

Lately he’s become passionate about getting trees to be planted closer to street corners, to reduce the size of heat islands at intersections.

Advertisement

“Some of the characteristics become sort of exaggerated with age, just like our ears get longer,” reflected Vanderslice. “So many of our really dedicated, wonderful, brilliant citizen volunteers are annoying.”

And Klotz can be, his fans and foes agree, pretty annoying.

“He’s brilliant,” said Vanderslice. “He’s absolutely brilliant. But — and he recognizes this — he does not have some of the skills that it takes to run an organization.”

“He is sort of an odd duck, but I think he means well,” said Wong, who said she “understands what Doug is trying to accomplish” but thinks his goals are unrealistic.

“The thing is, cars are kind of a fact of life,” she said. “It kind of stinks, but people need their cars.”

Ethics and action

Steve Gutmann, a Richmond resident who’s also vice president of the board for the anti-sprawl group 1000 Friends of Oregon, said the Richmond neighborhood Klotz has helped create is the one Gutmann and his wife had dreamed of when they moved to the area 14 years ago.

“We would ride our bikes up and down Hawthorne and Division just sort of imagining how great it would be if and when those commercial strips transformed from, frankly, pretty crappy strips into places where we would want to walk over to and spend our time,” Gutmann said. “And that’s happening.”

“We would ride our bikes up and down Hawthorne and Division just sort of imagining how great it would be if and when those commercial strips transformed.”

— Steve Gutmann, Richmond resident since 2001

Gutmann called Klotz a “neighborhood hero” for “taking a lot of the heat for policies that many of us here are benefiting from.”

Steph Routh, who served as director of Oregon Walks after Klotz had left its board, said one of the oddest things about Klotz is that she’d never seen him discouraged.

“It’s not in Doug to do nothing,” Routh said. “Ethics and action are one and the same. Doug treats goodness as a verb, not a noun or an attribute.”

Linda Nettekoven, another neighborhood advocate who has worked with (or against) Klotz on numerous issues since the Hawthorne Boulevard McDonald’s, called Klotz “a wonderful example of one of the people who make Portland a special place.”

“He has strong opinions, but he is willing to listen, and he is fun to argue with,” she said. “The notion that there are people in our community — and there are lots of them — who have stuck with issues across so many years and try to look at the bigger picture and see how the pieces fit together … I think that’s one of Portland’s great strengths.”

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Corrections 11/15: Earlier versions of this post misspelled Caffe Pallino and slightly misquoted Vanderslice.