In a big new story promoted using its new “watchdog” label, The Oregonian has determined that a wave of new apartments that account for 3 percent of Portland’s housing supply are the best way to start talking about a trend that is rapidly pushing Portland homes out of middle-class reach.

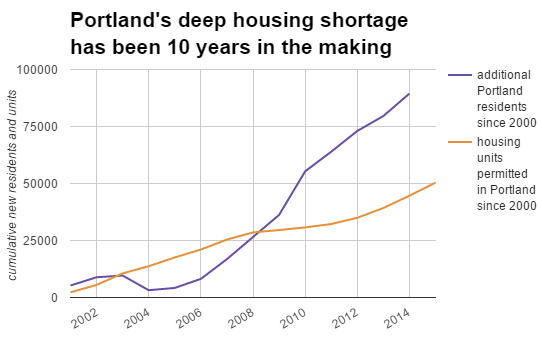

From 2006 to 2014, Census figures show, Multnomah County’s population grew 79 percent faster than its housing supply. The surge of apartments that began to open in 2012 have barely made a dent in the deep shortage that developed during the Great Recession, when housing construction nearly stopped but 10,000 people kept pouring into Multnomah County each year.

In 1,600 well-crafted words about Portland’s housing problems, the newspaper doesn’t find room to mention these facts.

Instead, reporter Jeff Manning and his editors suggest the opposite, writing that the cause of the 41 percent surge in Portland rents is “a real estate gold rush,” exemplified by “hundreds of micro-units” in desirable parts of Portland.

Here’s how an Oregonian editor chose to summarize the accompanying video: “Construction boom transforms Portland, pushes rents to new heights.”

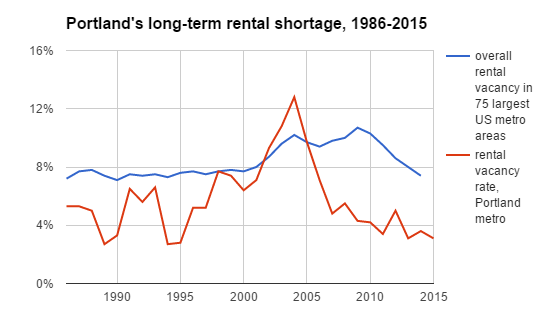

Manning’s piece does mention Portland’s low rental vacancy rates. But again and again, it returns to the implication that Portland’s 10,000 new units can somehow be a cause, rather than an effect, of the rent hikes that have hit nearly all of Multnomah County’s 300,000 housing units over the last few years and are, as the Community Alliance of Tenants warned last week, coinciding with a wave of no-cause evictions.

To his credit, Manning tells the wrenching story of this Portlander’s personal housing crisis:

Colby Gillespie, 63, had every intention of living the rest of his life in his studio in the Sovereign Apartments in downtown Portland. He lived in the building at Southwest Broadway and Madison since 1980 and the $750 monthly rent fit his grocery checker’s budget.

But the new owner of the building had other ideas. In May, Randall Investment Co. informed Gillespie and the residents of the other 43 units that a planned renovation required everyone to be out by the end of the year.

“I have no idea where I’m going to go,” Gillespie said. “I’m really angry. It’s all very cold and corporate.”

Gillespie and his neighbors are suddenly among Portland’s “displaced,” those low- and middle-income locals forced out by the boom. While the big new projects have gotten the headlines, smaller operators have been snapping up dozens of smaller, older apartment buildings.

Advertisement

There’s no question that Gillespie is a victim of Portland’s awful housing problem. As someone who can deal with $750 a month in rent, he’s not seriously poor; he’s simply working class. In a functional housing market, Gillespie might be uncomfortable but wouldn’t be in major trouble.

But the malfunction that made his eviction profitable — a demand for higher-end housing units that exceeds Portland’s existing supply of higher-end units — isn’t explored.

There’s been some great journalism coming out of Portland’s housing crisis. Two weeks ago, Portland-based Lee Van Der Voo of InvestigateWest combined shocking anecdotes and little-known public records to document the practices of American Homes 4 Rent, a Wall Street-run company that has used 85 subsidiaries to buy thousands of single-family homes, including 204 in Portland, and rent them out under contracts laced with hidden fees. It was a terrifying illustration of the ways profit-taking companies are milking the housing shortage for cash without creating new housing.

But despite lower-profile stories like this from last week, in which the Oregonian summarized a panel of experts’ perspective as “people are moving back into cities, but supply can’t catch up,” the paper’s marquee coverage not only chooses to neglect Portland’s supply problem. It also talks about the relatively few new units being created as if they’re the cause of Portland’s housing trouble, and it talks about developers as if they’re the only capitalists feasting off the problem.

In today’s Portland, where a home in a walkable, bikeable, transit-friendly neighborhood is just one of the conveniences of wealth, people who get around by foot, bike and transit because it’s affordable are among the worst-hit by our housing crisis. If tomorrow’s Portland is going to be any different, it’ll require journalism that helps point toward actual solutions.

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here.