(Photos: J.Maus and M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Traffic diverters: back by popular demand.

“If people are telling us ‘I don’t feel comfortable riding a bike on this street,’ then the greenway is not performing its intended function.”

— Roger Geller, PBOT bicycle planning coordinator

At their weekly meeting in City Hall this morning, Portland’s city council is poised to adopt a set of guidelines sweeping away an internal barrier that had led the city to avoid using diverters in many situations where they would improve a neighborhood greenway.

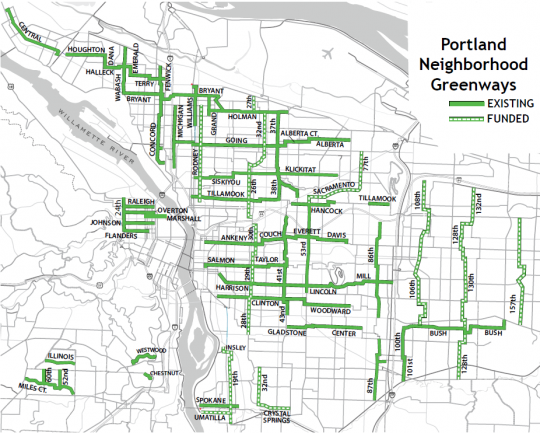

Neighborhood greenways are Portland’s name for the side streets that use sharrow decals, speed humps, signs and stoplights to make them comfortable for biking and other outdoor activity.

Traffic diverters are facilities like the ones at Northeast Tillamook and 16th or Southeast Clinton and Chavez that block cars from driving through certain intersections.

Wednesday’s council vote would be one of the biggest steps Portland has ever taken to enshrine neighborhood greenways as a higher priority than other side streets — and to acknowledge that the city must not only build new greenways but also tend to problems on the ones it has already built.

“More people are traveling on Portland’s streets,” the city’s transportation staff explains in a new report on neighborhood greenways. “Increased residential and commercial development is requiring new strategies for managing the neighborhood greenway system.”

The report and guidelines come in response to a year of sustained activism from pro-bike Portlanders for the city to use diverters more often. New diverters on Southeast Clinton have been the No. 1 issue for the upstart group BikeLoudPDX, and were one of the main requests in a rally that group organized at City Hall in June.

City officials say that message has been heard.

“People are saying ‘This is not comfortable, this is not safe,'” Portland Bicycle Planning Coordinator Roger Geller said. “If people are telling us ‘I don’t feel comfortable riding a bike on this street,’ then the greenway is not performing its intended function.”

The guidelines proposed in the new Neighborhood Greenways Assessment Report would essentially direct city planners and engineers to install a diverter on any part of a neighborhood greenway that sees more than 2,000 cars per day.

That means Southeast Clinton, Southeast Lincoln, Northwest Johnson, Northwest 24th and Southeast 130th would all get diverters to reduce non-local auto traffic.

In all, the report’s recommendations would trigger an estimated $1 million in improvements to a handful of the city’s existing neighborhood greenways, said city active transportation manager Margi Bradway, who has been the driving force behind the report.

According to the city’s study of traffic speeds and volumes throughout its network, new diverters and/or speed humps are needed on these existing routes:

• NE Alameda

• SE Ankeny

• SE Clinton-Woodward

• SE Lincoln-Harrison-Ladd

• NW Greenways, which includes short sections of several streets throughout inner Northwest

• NE Tillamook-Hancock

The city’s goal with speed humps would be to slow traffic until less than 15 percent of people are driving faster than the 20 mph speed limit on greenways.

The $1 million is unfunded. Bradway hopes that Wednesday’s council vote on the new guidelines (expected around 10 a.m.) will lay the groundwork for that cash being included in the city’s 2016-2017 budget.

Mayor Charlie Hales has already called for a new experimental diverter on Clinton to be built in the current fiscal year.

Advertisement

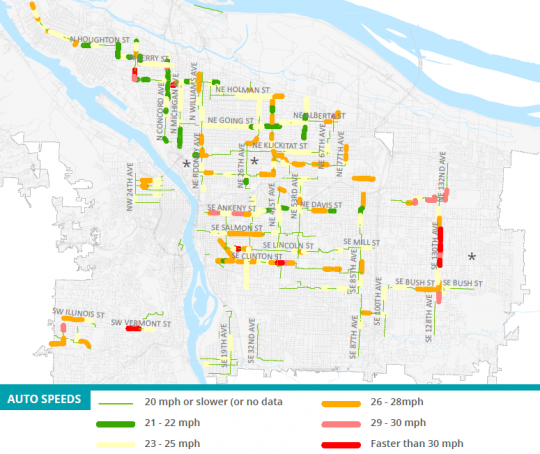

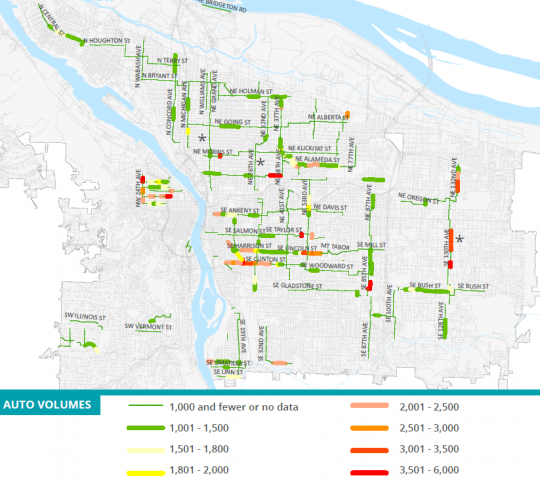

Earlier this year, we shared two advance tidbits from this report: a map showing traffic speeds on neighborhood greenways and another showing traffic volumes.

Of those two, the city feels that traffic speeds represent the bigger problem. Though the city is aiming for 20 mph speeds on its greenways, traffic moves faster than that on 84 percent of the system.

Traffic volumes are a smaller-scale problem. Only 9 percent of the system sees traffic volumes above 2,000 cars per day. But those trouble spots are concentrated in inner Northwest and Southeast Portland.

Both maps above also show major problems on the 130s neighborhood greenway in East Portland. That’s because the greenway doesn’t exist yet. It’s already scheduled to get speed humps, and the data suggests that it might need one or more diverters, too.

Here’s a useful chart in the report that shows why traffic volumes matter so much to the biking experience: on a street like Clinton that carries 3,000 cars per day, about 21 cars will pass a bike during a 10-minute trip.

In addition to the maximum of 2,000 cars per day, the report offers an “alternate guideline” that neighborhood greenways should never have more than 100 cars in a single direction over the course of an hour.

“The traffic volume during the rest of the day may be very low, but the significant increase in peak-period autos creates a high-stress environment for people biking during that time,” the report explains.

Understanding the significance of today’s report requires understanding a set of internal guidelines that few Portlanders have ever heard of.

It was created in the 1990s, when then-Transportation Commissioner Earl Blumenauer pioneered a program that let residents lobby the city to install diverters on their streets. The goal was simple: force car traffic to use arterial and collector streets instead.

But according to the rules written in those days, diverters couldn’t be used simply to swap large amounts of traffic from one local street to another.

If a proposed diverter on any local street would be expected to send a substantial number of cars per day to a different local street, the diverter couldn’t be built. The city saw no upside in merely moving the traffic problem around.

Today’s guidelines scrap that system. Even if a new diverter on a neighborhood greenway would send hundreds of cars onto other local streets, that would now be OK.

The new guidelines draw the line at 1,000 cars. Diverters still aren’t allowed to direct so many new cars to any single local street that its traffic exceeds that level.

The rationale for the rule change is simple, Geller said: neighborhood greenways are more than just local streets.

“It may be a local street for automobile traffic,” he said. “But it’s an important street in the city’s classification system for bicycle transportation.”

Correction 3:20 pm: A previous version of this post misstated the maximum amount of auto traffic the new guidelines will allow on non-neighborhood-greenway local streets. They will allow post-diversion levels up to 1,000 cars per day, not up to 1,000 additional cars per day.