(Photos: M.Andersen and J.Maus/BikePortland)

Central-city apartment dwellers might want to start looking into that whole car-free thing pretty soon.

An advisory committee composed almost entirely of residents of residential zones gave a general thumbs-up Wednesday night to a city proposal that could let residents of residential zones vote to prevent people who live on commercial streets from buying overnight parking permits in their neighborhoods.

Because most of Portland’s commercial main streets are zoned for mixed-use or employment, the proposed parking permit system — which would also charge residential permit holders a yet-to-be determined monthly or annual fee for curbside parking — would effectively let residents just off of commercial corridors remove curbside parking rights from residents of most nearby multifamily buildings.

The city’s idea is that such a system would lead developers of buildings on commercial corridors to include more on-site auto parking in their new buildings, or else to market their buildings more successfully to car-free residents.

Also looming over the talks, though in the background: the risk that too-stringent parking requirements might further limit Portland’s supply of additional housing, making rents rise even faster in older, more affordable buildings than they already are.

Most committee members seemed to think that the city’s proposed rules, which would put the biggest new burdens on developers and residents of commercial corridors, hit a useful balance.

“I think if the neighborhood went to a permit program, the developer would be incentivized to build parking,” said committee member Kristin Slavin. “If I had to pay for parking and was living in an apartment, I would rather know I had a spot.”

Main-street residents should get to buy permits too, some say

Though more than half of the committee members said they supported, or could at least live with, the general outlines of the city’s proposal (PDF), various members said they would prefer residents of mixed-use and employment zones to be able to buy parking permits too.

“I’m choking on that issue of a resident of a mixed-use building not having access to those permits, because I think that’s not fair,” said Ted Labbe, who nonetheless called it a “good proposal.”

Mike Westling agreed, saying that without an option for main-street residents to buy permits, the zoning-based system would be de facto discrimination against residents of multifamily buildings.

“We say we want to be housing-type neutral, but in practice, it’s not going to be housing-type neutral,” Westling said.

Allen Field said it seemed fair for residential permit holders to be allowed to sell their permits to other people who wanted them.

“People in mixed-use buildings should be able to get parking permits,” he said. “Developers are allowed to buy and trade development rights.”

Sue Pearce said she could imagine that scenario, too.

“I have visions of the black market and the price going up and up — and my second question is, is that really a problem?” Pearce said. “If people are willing to pay the price.”

How much should parking permits cost?

(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

When it came to the price the city should charge residents of residential zones for permits, several committee members said that $60 a year — a number thrown out by city staffer Grant Morehead as a figure that would be too low to achieve the desired effect — was too high.

“It’s going to increase the problem of Portland becoming an unaffordable city for a lot of people,” said Field of the $60 a year permit price. “A lot of people are one payment away from losing their homes.”

“For some areas, that’s really high, and that will be unaffordable to a lot of people,” agreed Gail Hoffnagle.

Others disagreed.

“If the permit price is around that $60, it seems like it’s not enough to get to the goals you’re talking about,” said Kurt Norback. “It can’t be too high, but it can’t be too low.”

Advertisement

Tony Jordan said a price in the tens of dollars a month would still be small compared to other costs of car ownership.

“The city doesn’t subsidize water,” he said. “The city doesn’t subsidize garbage. There’s lots of things that we make people pay for. … It’s fair to say that the cost of car ownership includes the cost of storing your car.”

“I don’t necessarily support punitive fees for car ownership, but I would love it if we would simply remove all the subsidies that society has for car ownership today,” said Chris Smith. “The ideal we’re trying to get to is a city where a car is a luxury good. Where you can choose to use a car but you don’t have to.”

Should neighborhoods get a share of the revenue?

The city, looking for consensus where it can get it, has so far avoided slapping a sticker price on its proposed overnight residential parking permits, or discussing how the revenue might be allocated. All the same, several committee members said neighborhoods that create parking permit systems for themselves should be rewarded with a share of the new revenue.

“The neighborhoods should have control of some of the money — 30 percent, 50 percent, 70 percent,” said Jordan. “It’s not like you’re taking money away and stuffing it in some pot downtown. … You’re putting it in and it stings less because you’re going to get a crosswalk or you’re going to get a beacon.”

Kay Newell had a similar suggestion.

“Every neighborhood in the city could say, we want this this and this pothole done,” she said.

Smith, who is a city planning commissioner as well as a member of the committee, sounded a similar note, saying he sees the parking reform effort as a way to prevent political backlash against urban infill and other policies that support a shift to low-car, low-carbon life.

“In pursuing policies that move us along, we’re creating change so fast that we’re creating backlash,” Smith said. “I think in some ways the central challenge of this committee is how do we keep moving forward in a way that has so much support in the body politic that they’re willing to let us keep doing that.”

Unheard voices and other problems

Though most committee members present Wednesday were supportive of the proposal, including people of various political stripes, various concerns were raised.

Hoffnagle, for one, didn’t seem to buy the notion that the permit system described would actually get developers to include auto parking in their apartment buildings.

“We haven’t addressed the root of the problem, which is apartment buildings with no parking,” she said.

Newell, longtime owner of Sunlan Lighting on Mississippi Avenue, said she worried there wasn’t enough discussion of “livability.”

“If our communities aren’t livable, inviting, we are going to create a ghetto,” Newell said. “That’s what Mississippi was 25 years ago. And we don’t want that anywhere in our city.”

No committee members or staff responded to that.

At a different point in the meeting, Pearce said she feared the committee was failing to follow the advice of one panelist in last month’s city-sponsored parking symposium: “protect the incumbent.”

Rebecca Kennedy, however, took issue with that.

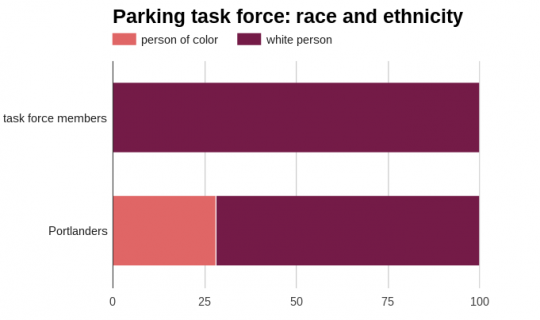

“We need to really think about balancing incumbency with stuff like affordability and equity,” Kennedy said. “While it’s not great that people’s streets are filled up with cars that aren’t theirs … we also live in a city that is getting increasingly unaffordable, and the idea that we’re going to favor incumbents — we’re talking about a certain kind of incumbent. We’re talking about a privileged incumbent. We’re talking about the people who are sitting around this table.”

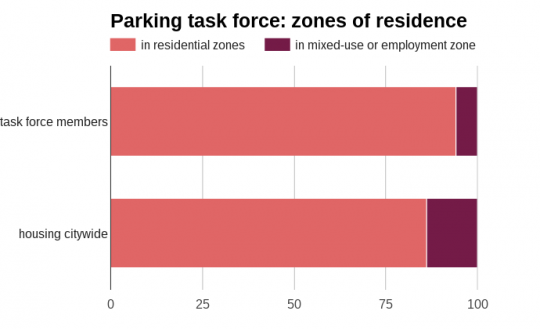

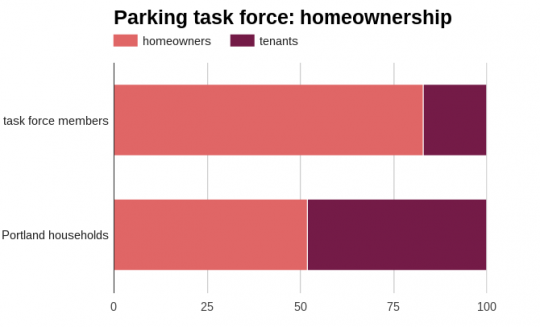

Of the 18 members of the city-selected stakeholder committee that weighed in on the issue Wednesday night, 17 (or 94 percent) said they live in residential zones. Of the 18, 15 said they were homeowners. Zero said they considered themself a person of color.

Sixteen percent of Portland housing units are in mixed-use or employment zones. Forty-seven percent of Portland households are tenants. Twenty-eight percent of Portlanders identify as people of color.

(The task force figures above apply only to members of the city’s “Centers and Corridors” parking stakeholder advisory committee who were present near the end of Wednesday’s meeting. The final two citywide figures come from the Census Bureau; the first comes from the city planning bureau.)

The city’s parking reform process will continue for the next few months, with the city working out more details of the proposal and vetting them with the committee. At that point Morehead and other staffers are expected to make a recommendation to the city council.

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here.