(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Most of Portland’s conversation about ways to create enough new homes to defuse our deep and ongoing housing shortage has focused on the four-story apartment buildings rising along a few main streets.

But there’s a growing awareness in Portland’s housing policy community that low-rise apartment buildings — let alone the taller buildings rising in the Lloyd, Burnside Bridgehead and Pearl — aren’t the only buildings that can increase the supply of housing in the walkable, bikeable parts of Portland. In fact, the other options might be more popular with neighbors, too.

The only problem: in almost all of Portland, creating such buildings is forbidden.

They’re called duplexes.

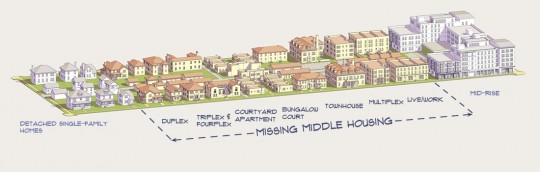

Last weekend, Portland micro-developer Eli Spevak led 20 people on a Pedalpalooza ride called “The Missing Middle,” focusing on what Spevak sees as the forgotten stepping stone between Portland’s sleepier, yard-and-driveway past and the bustling urban future being built on SE Division, North Williams and elsewhere.

Spevak borrowed the phrase from Berkeley-based Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design, whose website MissingMiddleHousing.com promotes many classes of housing that were popular in the cities of the early 20th century, but largely eliminated when the modern age of auto-oriented urban planning arrived.

When Portland’s first zoning plan was approved in the mid-1920s, local planning historian Steve Dotterrer said, what we now know as “single-family” zoning “was only applied in Laurelhurst, Eastmoreland, Overlook and a little bit of the West Hills. Everything else [away from rivers and streetcar corridors] was Zone 2, which allowed any kind of residential, from high-rise to single-family.”

High-rises, always expensive, were built only in the very heart of the city. Multiplexes, though, became common.

“But in 1959 the code was completely rewritten and for the first time autombile restrictions came in,” Dotterrer said. “The single-family zones were actually expanded to cover lots of the city.”

Fortunately, Portland’s bike-friendliest neighborhoods still retain a memory of this sort of housing — because it’s still very much in use. In fact, these are the housing units that Portland’s bike-friendliest neighborhoods are built on.

Not only do these buildings tend to cast shorter shadows and offer more bedrooms. Because they’re only one to three stories tall, they can be built with wood frames, which makes them significantly cheaper to build than taller concrete or steel apartment and condo structures.

During Sunday’s ride, Spevak led participants around a few blocks of inner Southeast and Northeast Portland, showing off building after building that would be illegal if it were built today, but remains in so much demand that nobody has wanted to use it for anything else. In some cases, they seemed likely to be the most affordable homes remaining in this part of Portland.

And maybe even more remarkable: they fit right in.

To be fair, these duplexes, four-plexes, internally divided homes and courtyard buildings weren’t small, and may well have changed the feel of the neighborhood when they were built. But compared to a three- or four-story apartment block, they’re next to nothing.

Today, Portland’s most common residential zone, R5, allows duplexes in only one situation: when they’re on a corner lot and one door faces in each direction.

It’s easy to see how, if the city were to re-legalize mid-block duplexes and internal home divisions in residential neighborhoods, central Portland could gradually absorb thousands of these small but often family-sized units without massive changes to the way the city looks or works.

Advertisement

Spevak also argues that legalizing such buildings could reduce 1:1 demolitions by making it more profitable for developers to add units inside existing houses rather than tearing old ones down.

While looking at all these older homes, it’s worth keeping in mind that Portlanders built cheap, flimsy homes in the 1920s, too. We don’t see very many of those because they’ve all been torn down by now. The best-built homes must have cost a fortune in those days; decades later, they’re often the best bet for an affordable home in Portland’s much-loved middle.

Here’s an extra bonus home we stopped at during Sunday’s ride. It’s not attached to any other home. Can you guess why it’s illegal?

Scroll down a bit for the answer.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Not enough car parking.

For decades, city code has forbidden the first car length away from the sidewalk from being the only auto parking space on a single-family home, except in the case of single-family homes that sit within a block or two of frequent transit lines. According to city filings, a local green architect went through a special design review process in 2007 to persuade the city to waive the extra parking space requirement as part of his extra-low-impact home.

Would it be possible for Portland to re-legalize homes like the ones above? Maybe.

Responding to spiraling housing prices and residents’ worries about increasing home demolitions, the city is in the early stages of amending its code for residential infill. And next Tuesday, the Portland Planning and Sustainability Commission will discuss how and where Portland is going to fit new residents over the next 20 years. If you’d like to comment on whether some of the housing types that have made central Portland what it is should be re-legalized, you can email psc@portlandoregon.gov before then.