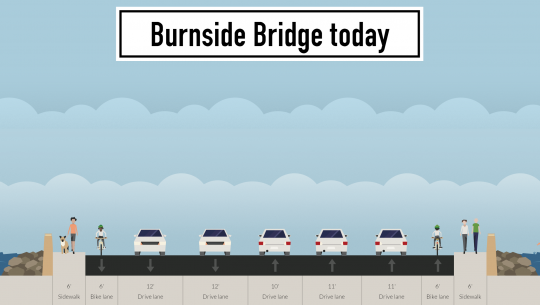

(Images via Streetmix.net – mix your own)

Anyone who’s ever been close to the Burnside Bridge’s eastbound lanes out of downtown has heard it: the roar of car engines as people see three mostly empty lanes of roadway ahead of them and hit the gas.

Thirty seconds later, of course, they’ll likely as not be sitting at the stoplight on the east landing of the bridge, along with everyone who didn’t jam the gas pedal.

Why does the Burnside Bridge need three lanes of eastbound auto traffic when it has only two lanes westbound?

Which raises the question: Why does the Burnside Bridge need three lanes of eastbound auto traffic when it has only two lanes westbound?

We don’t yet know much about the split seconds that killed Ben Carlson and wounded Bridget Larrabee Sunday, though according to KGW the man who hit them with his car, Douglas Walker, had “choked on a soft drink, passed out and lost control” before careening onto the sidewalk. But at 2 p.m. on a weekend afternoon, we know the situation on Burnside’s eastbound roadway at the time: almost certainly vast and empty.

The Burnside was built so wide because, before 1950, each direction had two lanes of auto traffic and one lane for streetcars. If we returned to that pattern by removing one of the two eastbound passing lanes, would it change the freeway feel of the street as it rises out of downtown?

If the lanes were changed, could the road space be used in other useful ways? What if better traffic barriers were part of that?

I’ve spent much of today talking with traffic experts and officials and looking at what could be done to make Burnside less of a highway and more of a street.

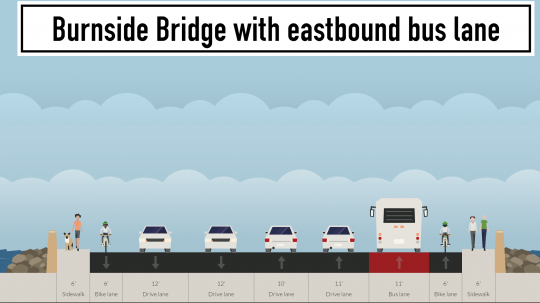

Buses carry 14 percent of eastbound traffic across the Burnside but get 0% of the lane width

Three TriMet lines run on the Burnside: the frequent-service 12 and the almost-frequent 20 and 19. (TriMet has said the 20 is a candidate for upgrading to frequent service.) During rush hour, every person driving or biking already knows that anyone in the right eastbound lane of Burnside downtown is likely to get stuck behind a loading or unloading bus, so many people try to merge left and then merge right in front of buses on the uphill.

And here’s the thing: TriMet estimates that the buses carry about 3,780 eastbound passengers a day. Assuming that the average car or truck has 1.2 passengers, that’s already 14 percent of all eastbound vehicle traffic across the bridge. (Cars carry about 82 percent, bikes 5 percent.)

What if the rightmost lane of the Burnside were dedicated to buses? This would maximize space efficiency on the bridge by letting the most space-efficient passengers (bus riders) jump the rush-hour traffic queue just as bike users are currently able to.

This would mean one fewer through lane of auto traffic could fit through the eastbound signal at MLK, so during two hours each weekday, some people driving would probably have to sit through an additional 60-second signal cycle. But because they’d be doing it in the middle of a half-mile-long bridge, this wouldn’t lead to any trouble elsewhere in the system.

The Burnside Bridge area is growing like crazy and bike traffic keeps rising

As we’ve reported, some of the city’s bike-friendliest new apartment buildings are about to go up in the Burnside Bridgehead area near the bridge’s east landing. But what good are on-site facilities if it’s not comfortable or attractive for someone to walk or ride a bike across the Burnside itself?

Bike traffic across the Burnside Bridge keeps rising steadily, the latest city counts show. Working with developers, the county and city could turn the Burnside Bridge into a hey-look-at-this green carpet into downtown.

Because the Burnside Bridge raises 45 degrees into the air during its lifts, planters, jersey barriers and maybe even grassy strips wouldn’t be possible across the span. But those elements, especially a little greenery, could add a lot just to the other parts of the bridge, and make the whole area the sort of place people naturally slow down and appreciate rather than zooming through as fast as possible — even when they’re behind a wheel.

There’s even enough room to do both

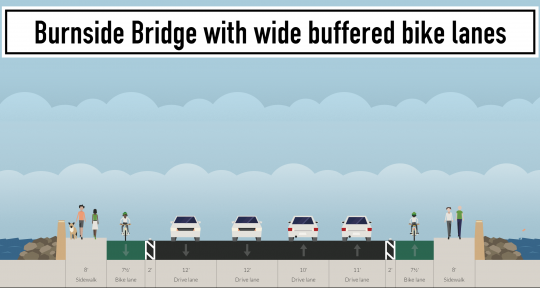

Here’s something else: given the fact that 12-foot-wide traffic lanes like the westbound ones on the Burnside are known to be unsafe, why not narrow them a little and make room for high-quality facilities for both bike and bus?

Would an extra curb built into the roadway beside the bike lane have saved a life yesterday? It’s hard to say. Certainly curbs have the effect of narrowing the roadway and leading people to drive more carefully. In any case, there’s no question that people strongly prefer to bike in curb-protected lanes, not just because they feel safer but because they feel more comfortable.

If we did this on the Burnside, people would get 15 percent of the eastbound space of the road bed if they travel by bike; 28 percent if they travel by bus; and 56 percent if they travel by car.

That gives more space per person to people biking and busing than people driving. But it’d almost certainly make more people choose bikes and buses. And in a city aiming to get 25 percent of trips on transit and 25 percent on bike, it seems only appropriate. How else is this change going to happen?

Advertisement

One fewer eastbound lane wouldn’t worsen gridlock, experts say

I asked some transportation pros what they thought about the concept of removing an eastbound lane from cars. Would it cripple auto traffic across the bridge, which is already crowded during rush hour?

It wouldn’t. At worst, people choosing to drive over the bridge during rush hour would have to wait through an extra traffic signal cycle or two, and because the bridge is so long, it wouldn’t lead to spillover effects elsewhere.

Here’s Ray Delahanty, a transportation planner for DKS Associates:

The eastbound throughput is limited by that signal at Burnside/MLK. If you were going to design that eastbound approach to the signal in a completely motor vehicle-centric way, maximizing throughput at the signal, you’d want to make sure you had three eastbound through lanes and a right turn lane extending far enough back to store all the vehicles that need to get through during the light’s green phase. That’s pretty close to what they have now.

So, back of the envelope, assuming 60 seconds of green time each cycle and a gap of two seconds between each car, you’d need queue storage for 30 cars per lane (less for the right-turn lane, since they will flow more slowly due to turning and, presumably, yielding to pedestrians). Assuming 25′ per car, that’s 750′. Anything beyond 750′ is excess queue storage for vehicles that were not able to get through the signal on the first try. And if it’s excess queue storage for vehicles that aren’t going to be able to make it through the signal, you don’t need three lanes — two will do fine. The bridge is 2600 feet or so, so there’s definitely room to do SOMETHING. And remember, this is thinking of the design purely from a motor vehicle throughput perspective.

Another consideration — you would have to merge from 3 lanes to 2 lanes at some point, since West Burnside is 3 lanes approaching the bridge eastbound from downtown. It would be tough to rightsize this section, since it does get really congested — a lot of times when I take the 12 in the evening, you get stuck for several signal cycles in between SW Broadway and SW 2nd. However, if you could make the right lane bus-only, that would solve the problem somewhat. Anyway, traffic engineers hate lane drops/merges, so that’s a tough sell if you’re thinking about having two lanes merge together eastbound once you get through the signal at SW 2nd. Although the “safety” issue here would probably mostly be vehicle/vehicle sideswipes, which aren’t anything remotely close to what we saw on the bridge this week in terms of severity.

One last thing — my experience is that Multnomah County doesn’t have any policy issue with doing restripes or other cross-section changes on bridges as long as the changes aren’t a liability. They defer to PBOT on the traffic considerations, as they did at the east end of the Hawthorne when the buffered lane and sidewalk were added eastbound at Grand. I don’t think ODOT has an interest in the Burnside either, so it’s really a question for PBOT traffic. … I’d be surprised if they wouldn’t seriously consider major cross-section changes on the Burnside.

Here’s Todd Mobley, a traffic engineer and principal at Lancaster Engineering, on the possibility of mitigating any such delays:

The bridge itself could afford some protected facilities to avoid crashes like we just saw. The intersections (particularly the first one) on the east end could have a different type of treatment for people on bikes or other vulnerable users. It is still really wide at the intersection, so depending on what the protected treatment would be coming across the bridge, it could transition into something different at the intersection that may have different capacity/delay impacts.

County and city: We’ll be discussing possible changes

As with most of Portland’s Willamette River bridges, Multnomah County controls the Burnside Bridge. I asked county spokesman Mike Pullen if he had any comments on possible lane reallocations.

Here’s what he said:

The city is the road authority for the sections of city roads that cross the county bridges. For example, the city can ask the state to change the speed limit on the bridge. In 1995 for example the city decided that the volume of bike traffic on the Burnside Bridge sidewalks had increased to the point where it made sense to eliminate a traffic lane to create two bike lanes and move bikes off the sidewalks.

The city and county work together on these projects, but we play different roles. On the Morrison Bridge there was a history of crashes from motor vehicles spinning out on the old open steel grating deck on the lift span (since replaced). A crash there led to a pedestrian fatality on the sidewalk. The city and county engineers agreed that a crash barrier was a sensible improvement on the Morrison Bridge due to conditions and the crash history there.

The Burnside Bridge hasn’t had a similar crash history. Yesterday’s tragedy will need to be looked at to determine if patterns are changing or if this was a freak accident.

And here’s city spokeswoman Diane Dulken:

The police are still investigating, and we look at all incidents and the circumstances behind them and then look at what safety improvements may be warranted and may be possible. … I cannot say what we will be doing but we will be having a conversation. … It’s too early for us to comment on any specific proposal. there are other options, but right now this is the early stage.

According the city’s Vision Zero safety map, the Burnside Bridge (including the intersections immediately east and west, which are recorded as the site of collisions on the bridge itself) saw 126 reported traffic injuries from 2004 to 2013. Eight of those people were biking, 14 of them were walking and 104 were driving.

Update 6/16: The sidewalk widths here were estimated using Google Earth because the city and county don’t have exact figures. On the bridge span, the sidewalk and rail area is nine feet wide total.