(Newspaper images: Oregonian archives at Multnomah County Library)

Slow-moving, prosperous and desirable arterial streets are nothing new; they’re just a return to the traditional ideas of our great-grandparents.

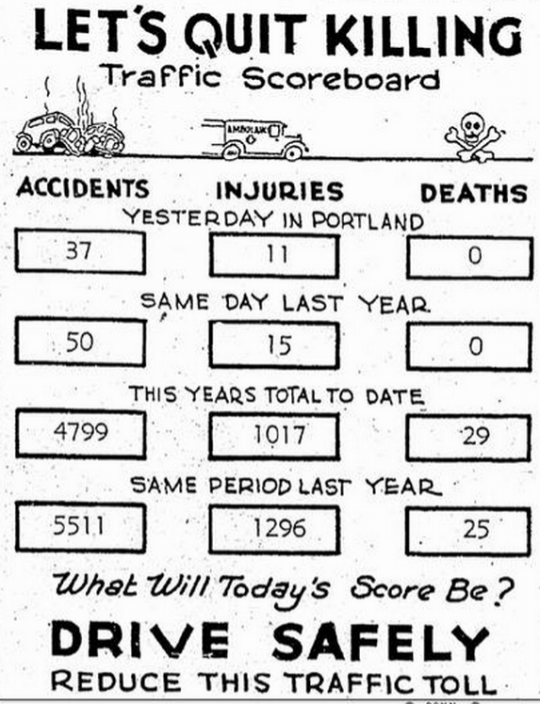

And here in Portland, a citywide goal to take public responsibility for traffic fatalities isn’t new, either. In the 1930s, as they felt their city changing fast, our great-grandparents’ generation responded with what became a nationally-known campaign that was strikingly similar to Vision Zero or the Dutch Stop de Kindermoord movement of the 1970s.

The campaign was called “Let’s Quit Killing,” and it was a collaboration among The Oregonian, the Oregon State Motor association, Mayor Joseph Carson, the police department’s traffic division and a citizen “army” of volunteer infraction-spotters.

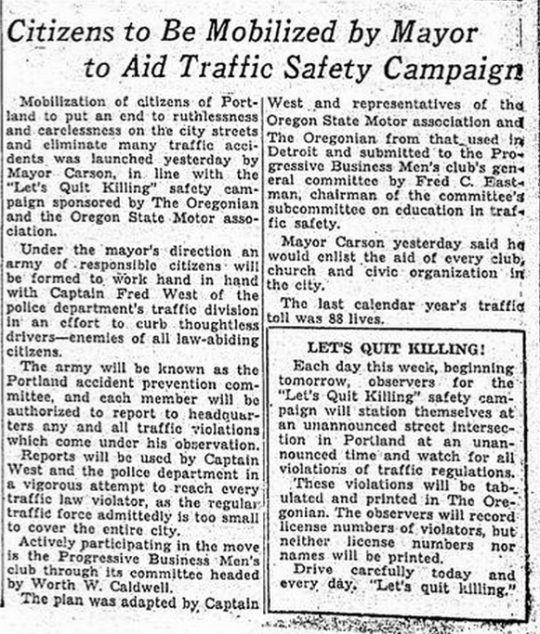

Here’s some Oregonian coverage from 1935:

Mobilization of citizens of Portland to put an end to ruthlessness and carelessness on the city streets and eliminate many traffic accidents was launched yesterday by Mayor Carson, in line with the “Let’s Quit Killing” safety campaign sponsored by The Oregonian and the Oregon State Motor association.

Under the mayor’s direction an army of responsible citizens will be formed to work hand in hand with Captain Fred West of the police department’s traffic division in an effort to curb thoughtless drivers — enemies of all law-abiding citizens. …

The plan was adapted by Captain West and representatives of the Oregon State Motor association and The Oregonian from that used in Detroit. …

Mayor Carson yesterday said he would enlist the aid of every club, church and civic organization in the city.

The last calendar year’s traffic toll was 88 lives.

Each day this week, beginning tomorrow, observers for the “Let’s Quit Killing” safety campaign will station themselves at an unannounced street intersection in Portland at an unannounced time and watch for all violations of traffic regulations.

These violations will be tabulated and printed in The Oregonian.

The history of this campaign was unearthed early this morning by Aaron Brown, the board president of Oregon Walks, while he was researching the history of street-safety advocacy in the Multnomah County Library’s newspaper archives.

Here’s another notice in the O:

Advertisement

“You know it was a big deal because the first thing we thought to do with it was to challenge Seattle,” Brown adds.

Mr. Riley pointed out that Portland is now ahead of Seattle in keeping the death toll down, but he felt that such a competition between the two cities would contribute much to the “Let’s Quit Killing” campaign, save lives and bring about much more careful driving.

Mr. Riley declared that the great toll is now being taken among persons of 50 years or over. He pointed out that Portland had but 64 deaths last year while Seattle had 85.

The campaign seems to have worked pretty well. News of its success reached Hopkinsville, Kentucky, where the New Era newspaper wrote:

The automobile death rate can be reduced. And the reckless and inconsiderate drivers, who are responsible for some 36,000 deaths a year in this country, can be curbed.

A number of cities have proven this. One of them is Portland, Oregon, which has been carrying on a “Let’s Quit Killing” campaign that has produced fine results in a relatively brief length of time. Where the national automobile death toll during the first ten months of this year, was at the highest point on record, traffic fatalities in Portland declined about 25 per cent. …

The local judiciary has co-operated by levying sizable fines and prison sentences to violators of the traffic laws.

The automobile, properly handled, is one of the most useful and pleasurable servants of man. The same automobile, improperly handled, is one of the most lethal of weapons.

The Portland Traction Company, one of our privately-run streetcar systems, had a vested interest in good walking — and, apparently, an understanding of multimodality that we sometimes struggle with today. In 1937, transit tickets were emblazoned with the shared pledge “I Will Drive Safely.”

Things took a turn eventually, though.

“As Peter Norton’s book suggests, the movement started with a lot of admoninations towards motorists but unsurprisingly, over time it got increasingly hostile towards pedestrians,” Brown writes.

Traffic accident analysts of the Oregonian-Oregon State Motor association “Let’s Quit Killing” campaign are turning up data which indicate that ambulators on public thoroughfares should stiffen their shoulders to bear a sizeable share of responsibility for motor mishaps. … In Portland this year 33 of the 49 dead were pedestrians.

Portland thus continues her reputation as “the most dangerous city to set foot in” in the United States.

The last mention of the campaign in The Oregonian seems to be from September 1939, three weeks after World War II began. By that point, the phrase was being used in a letter to the editor (from a man who himself worked as the editor of a publication called “Automotive News” – presumably the Jonathan Maus of his day) to attack the ideas of traditionalist traffic engineers and usher in a new concept of “traffic safety”: removing obstacles from the roadway.

How soon must the citizens of Portland organize a traffic vigilance committee to halt the erection of accident-insuring, death-inviting obstructions in our city streets by our “traffic engineers”? I search in vain for non-official defenders of the wide concrete wall that bisects Interstate avenue, such things as the new tombstones at Fifty-seventh and Sandy. …

I shudder when I think of what will happen to life and property when fog and rainy darkness obscure the pillboxes, concrete walls and one-lane chutes that obstruct our streets. Will the motorist — ignorant stranger or forgetful, heedless or glare-blinded Portlander — be solely responsible for accident, injury and death as our “traffic engineers” use city streets as a proving ground for every traffic-control idea they hear about?

Isn’t there some power that can restrain this mad urge to convert our city streets into an anti-tank no-man’s land?

Apparently there was.

For a while, at least.

— If you’re a local transportation history buff like we are, browse our archives.