(Photo by J Maus/ BikePortland)

This post is part of our SW Portland Week.

It would certainly be ironic if Southwest Barbur Boulevard became the first arterial in Portland to receive a Copenhagen-style protected bike lane retrofit through a high-destination commercial area.

But that’s exactly what might happen if a regional committee chooses Barbur as the best route for a major new transit line. And getting around outer Southwest Portland would certainly be transformed.

“Barbur and I-5 are the options, and we’re not putting bikes on I-5. Barbur is the only option. And I think that makes it different from almost any other street in the city.”

— Anthony Buczek, Metro

“It is the flat route through the West Hills,” Metro engineer Anthony Buczek said Thursday. “Barbur and I-5 are the options, and we’re not putting bikes on I-5. Barbur is the only option. And I think that makes it different from almost any other street in the city.”

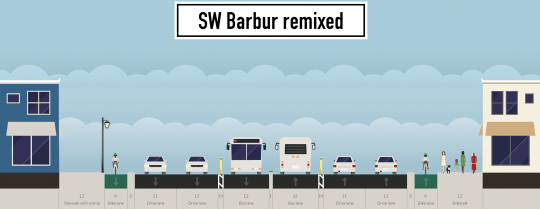

If the light rail or dedicated busway lands on Barbur, Buczek said TriMet is currently assuming that 16 feet of roadway, eight on each side of the street, would be dedicated to biking facilities. And because adding a 28-foot transitway to Barbur is already expected to require rebuilding the curbs and acquiring new land from adjacent property-owners, the region would get to build Barbur’s bike lanes and sidwalks pretty much any way it wants.

In short, there’s a chance here to completely rebuild one of Portland’s most car-oriented arterials into a world-class facility, with the federal government paying for half of it.

There are, however, four things that could send the plan off that course.

1) The transit line could go along the freeway instead

(Photo by M Andersen/BikePortland)

It’s far from a sure thing that Barbur will be chosen for the transit line’s route through Southwest Portland. A steering committee of elected officials from around the region might instead recommend a path on the hillside immediately northwest of Interstate 5. Commissioner Steve Novick said Friday that the Oregon Department of Transportation has been urging consideration of the freeway option.

“Which I think many people in the city aren’t excited about,” Novick continued.

In an interview Thursday, Southwest Neighborhoods Inc. transportation committee chair Roger Averbeck agreed that a Southwest Corridor plan that didn’t include changes to Barbur would be unpopular with many people he represents, in part because Barbur must be built more densely, and presumably made more pleasant to spend time on, if the transit line will have enough ridership to justify its cost.

“If we can’t tame the beast that is Barbur, that’s going to be more controversial,” Averbeck said.

Advertisement

Buczek and Metro planner Michaela Skiles said it’s not yet clear whether the freeway route would cost more or less than the Barbur route. Buczek said a freeway route would be reminiscent of TriMet’s Green Line along I-205:

While a route along Barbur would be more like the Yellow Line along Interstate Avenue, except with a second general travel lane in each direction rather than parking lanes.

Officially, the plan is to improve Barbur for biking and walking within 1/2 mile of transit stations even if the transit line runs along I-5. But if Barbur’s curbs aren’t being moved to make room for transit lanes, the biggest changes to the corridor might get scrapped.

2) High-quality bike lanes might be seen as taking up too much space

Continuous strips of land along a busy street are expensive. When every foot is precious, it’s easy to imagine 16 feet of bikeway coming to be seen as excessive once costs come into focus.

Meanwhile, car lanes may take up 48 feet of roadway width. Buczek said the assumption is that Barbur’s would be either 11 or 12 feet wide after the rebuild.

“We’re hoping for 11,” Buczek said. But the road currently belongs to the Oregon Department of Transportation, so it’s largely up to that agency.

Because wider lanes are known to encourage speeding, the Association of American State Transportation Officials says that on urban streets with many traffic signals and 35 mph speed limits or less, lanes should be as narrow as 10 feet.

3) Money might run short

Another possibility, as we reported Monday, is that the line might include a rail tunnel beneath Marquam Hill. Though the line would probably meet up with Barbur’s commercial strip eventually, tunnel construction could add a billion dollars to the price of the project, sucking up all available funding and forcing more corners to be cut elsewhere.

“The tunnel thing is hard,” Novick said. “We don’t know where we’re going to get the money for local match for any options.”

4) Suburban voters might kill the transit project

(Photo by M Andersen/BikePortland)

Last spring, Tigard voters gave themselves the right to vote directly on any high-capacity transit in their city. If they vote to block transit, it’d likely kill the Southwest Corridor project.

Last fall, Tualatin voters gave themselves the right to vote directly on any light rail transit in their city. Though that wouldn’t prevent dedicated bus lines, bus service might be seen as infeasible because even the big vehicles associated with bus rapid transit don’t carry as many people as light rail transit.

“During the peak hour, LRT could run at 7.5-minute frequencies, while BRT would need to run at 3-minute frequency to serve demand,” Metro spokesman Craig Beebe said. Because that’d require more than twice as many drivers — until self-driving buses might come into use, at least — that’d approximately double the cost of operating the new line.

On the other hand, halving the time between transit arrivals would certainly make the line convenient to use.

Even in a best-case scenario where Tigard and Tualatin sign off on the Southwest Corridor, the project isn’t expected to be built for 10 to 20 years: between 2025 and 2035.

(Photo by M Andersen/BikePortland)

It’s a long time to wait, especially for a day that might never come.

On the other hand, Buczek said, the fact that the Portland region is planning to deal with increased traffic by adding transit lines and bikeways, rather than widening the road to six auto lanes, is itself unusual.

“Fortunately, no one’s talking about that, because we live in a sane place,” Buczek said. “If we were in Phoenix, we’d be talking about that.”

“If we were in Florida, we’d have already built it,” Beebe added.