Only in Portland would a regional planning agency host a lunchtime event titled “Bus Rapid Transit 101” in a movie theater with free popcorn.

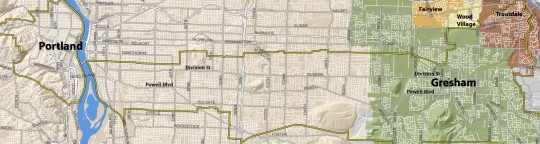

That was the setting yesterday for a meeting hosted by Metro to introduce Portlanders to their Powell-Division Transit Development Project. The planning effort is just getting started and the aim is to create the region’s first bus rapid transit (BRT) service on a 15-mile route along SE Powell and Division streets between Portland and Gresham.

We heard from Brian Monberg, a principal planner at Metro, and Alan Lehto, TriMet’s director of planning and policy. Both men extolled the many virtues of bus rapid transit as a way to solve the traffic issues that plague this busy corridor while spurring development and more transit use in general. (The problem and their proposed solution reminded me of how bike advocates make the case for cycle tracks, more on that later.)

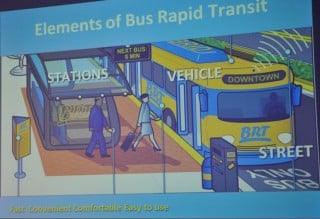

But what exactly is BRT? Think of it as a mix between Copenhagen’s cycle track network and Citibike in New York City — except swap in buses for bikes. Bus rapid transit systems feature dedicated and prioritized road space for buses along with custom-branded stations and vehicles with drop-dead simple fare and boarding systems. The idea is to make bus transit faster, easier to use, and more efficient.

And it works. BRT has become a viable option to rail transit in over 160 cities in the U.S. and around the world.

Advertisement

Along Portland’s Powell-Division corridor, bus transit is already extremely popular. It’s home to the number 4 and 9 bus routes — both of which are “frequent service” lines and among the most heavily used in TriMet’s system. Lehto shared in his presentation yesterday that the number 4’s stop at SE 82nd and Division sees 18,000 on/offs per week — close the capacity of Providence Park.

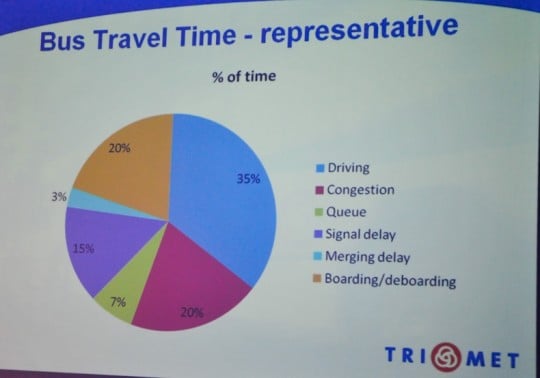

Unfortunately though, these buses currently spend more time stopped than moving more time stopped in traffic than TriMet would prefer. According to a recent estimate of bus travel time, TriMet operators spend about 55% of their time stopped; a mix of idling in traffic (20%), waiting for people to get on or off (20%), and waiting at signals (15%). The estimates put actual driving at just 35% of total travel time.

To combat those numbers, Metro and TriMet envision a redesign of Powell and Division that gives more space to buses and could also include traffic signal priority, improved stations, and so on. Among the lane configuration types under consideration are everything from physically separated bus-only lanes adjacent to a center median island (where people would board) to curbside bus-only lanes, queue-jump lanes, and traditional mixed-traffic lanes.

At yesterday’s meeting, Lehto said the ultimate design will likely include a mix of approaches: “Because it’s a 15-mile corridor that varies in its character and traffic conditions it’s not going too look exactly the same for the entire length. The design will focus on places where there’s the most congestion.”

“How can we be accommodating to all of the roadway needs, yet move forward with transit?”

— Alan Lehto, director of policy and planning for TriMet

With an improved transit experience, TriMet is betting they’ll see a spike in ridership not only among current bus users, but a whole new type of rider. “BRT,” Lehto said, “can be more attractive to people who haven’t even tried buses yet.”

The pitch for BRT sounds a lot like what a pitch for a cycle track network, yet there seems to be no consideration of cycling as a serious transportation mode in this project. There was scant mention of cycling or new bikeways at this meeting, other than brief references as something that needs to be “accommodated” or as an example of one of the “trade-offs” that might make planning the transit line more complicated.

“How can we be accommodating to all of the roadway needs,” Lehto wondered, “yet move forward with transit?”

I followed up with Lehto after the meeting via phone to ask him how BRT might impact existing and future bikeways on Powell and Division (both of which are targeted for bike access improvements in the 2030 Bike Plan). “The only answer I could give you right now,” he replied, “is… we just don’t know. There are so many users, you can never carve out space for absolutely everybody.”

Like TriMet has done (to mixed reviews) on their Orange Line, this project will surely include bicycle access improvements in the corridor. But as for a major bikeway line on the corridor alongside alongside BRT, Lehto said, “I can’t say we have a vision for how that works yet.” TriMet can do “pieces of the bikeway,” he said, “but not the entire project.”

TriMet is a transit agency, not a transportation agency. And as such, they have no obligation (or funding) to build bikeways. But what about Metro?

Portland has a history of building major transit projects (Interstate MAX, Eastside Streetcar, Orange Line, and so on) without also building the necessary and complementary cycling infrastructure or respecting how the new transit lines impact existing cycling routes. I asked Metro why they’ve started this process with a transit-only approach instead of seeing it as a “transportation project” that might also include serious consideration of cycle tracks. A spokesperson told me to, “Stay tuned over the first part of 2015… when we’ll be engaging people in those types of conversations.” That’s not the answer I hoped for.

Portland’s major commercial and roadway corridors are in desperate need of better transit and high-quality bike access. Isn’t it time we started planning for both?

I’ve scheduled an interview with Metro planner Brian Monberg next week to learn more about this project and how bicycling fits into it (or doesn’t). Stay tuned.

– There are still many more opportunities to weigh in about this project. Metro is planning a series of workshops in February and a steering committee to focus on design ideas in March. They hope to present a final recommendation in winter 2015, which would be followed by two years of design and then construction in 2018.

Learn more about the project on Metro’s website.