(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

A Portland startup is marrying the 1980s concept of “screwed and glued” modular frames with modern computer machining to dramatically cut the price of a custom handmade bike.

Its founder’s goal: a chain of minimalist, 600-square foot Apple Store-esque retail shops across the country, each one able to fit and service a line of Portland-built bikes as colorful and distinctly branded as iPods.

The man behind the plan is Rich Fox, a former innovation director at Nike and lead design strategist at Zeba Design. For the last 30 months, he’s been working from his basement to line up the components, branding and suppliers for a product that launched this morning on Crowdsupply, a Portland-based crowdfunding platform.

If there’s demand, Fox aims to open the first Circa retail shop in Portland next spring.

“Most of the bikes that are currently made here in the States, a bare frame will frequently cost $3000 and it will take anywhere from three months to five years to get that frame to you once you order it,” Fox said in an interview at his Northeast Portland home this month. “There are just very few people who can afford that kind of a product, in my opinion.”

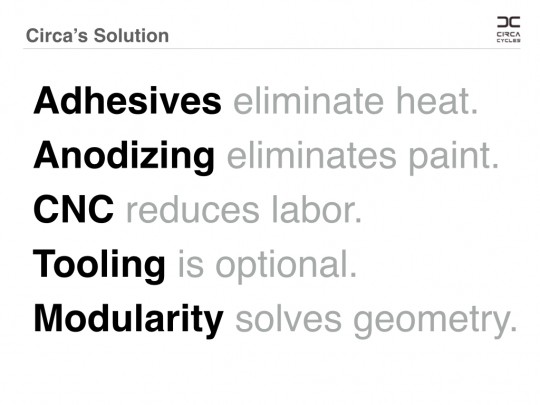

So Fox says he’s broken down the major cost factors behind bike manufacture…

…and found a way to cut each of them, which he’s dubbed the “Mabel” process.

“I want to be Portland’s affordable handmade bike,” Fox said. “And in order to do that, I just had to really rethink the handmade process to make that happen.”

Advertisement

The process he’s developed, which uses CNC (computer-controlled milling) to shape the frame’s joints and adhesives to hold them in place, will deliver a 21.5-pound custom bike in the size and color combination of the owner’s choice in 10 days or less.

Circa’s frames sell for $1,100 and the completed bikes start at $1,500, with “town,” “city” and “road” versions that go up to $2,100.

The crucial tactic in Fox’s method, glue, is a tool he said the bike industry moved away from in the mid-1980s.

“Carbon started to come on the scene, and carbon was very sexy,” he said. “There were all sorts of fun swoopy doopy shapes you could do, so from a marketing standpoint everybody got distracted and wanted to see all the things you could do with carbon.”

But carbon-fiber frames are just too expensive for a very large market, Fox thinks. Glue and anodized aluminum are better and faster.

“We glue airplanes together; we glue race cars together,” Fox said. “So we can glue bikes together. Why the hell not?”

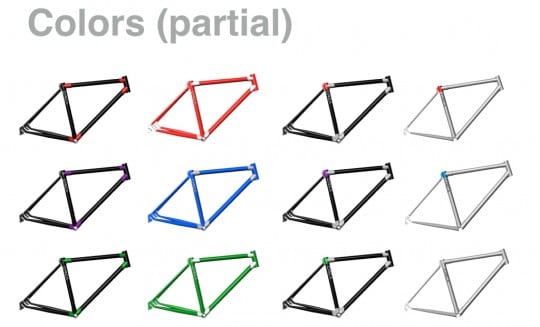

The distinctive three-color frame that has resulted is built for a designer’s eye: the joints are angled to create parallel lines and a sense of unity across the bike.

Fox’s first test ride of his prototype was during February’s snowstorm. He’s put 500 miles on it since.

In order to guarantee his turnaround times and rapidly iterate his production process, Fox’s milling and piping suppliers are all in Portland. He intends that to remain part of the company’s identity and brand.

The bikemaking process is only part of Fox’s plan to shake up bike retail. He also wants to draw on ideas from Tesla and Apple to create a brand-specific bike shop.

“A typical bike shop is overwhelming from a sensory standpoint,” he said. “There’s too much to look at. There’s nowhere to rest your eye and there’s nowhere to rest at all in many of those joints. I’d like to have much more of a boutique experience.”

In Circa’s Portland shop, Fox says, the walls will be bare, but (he hopes) a glass wall will let people in the 600-square-foot retail space see into the larger manufacturing space behind.

If the Portland store is successful, his long-term goal would be to license franchise stores in cities like San Francisco, New York or Boulder, Colo.

Then again, he says, there’s also a chance that Circa’s crowdfunding campaign might show that people aren’t enthusiastic about the concept.

“If people look at this and say ‘That’s nice,’ and walk away, then I need to find another day job, you know?” he said lightly.