(Image: Google Street View.)

In 2002, looking for future bottlenecks in its road system, the City of Beaverton was troubled by traffic projections for the corner of Southwest Farmington and Murray, one mile west of its historic downtown.

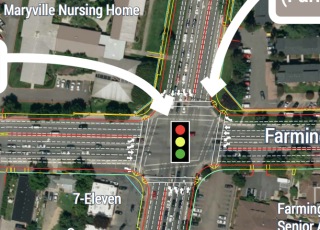

intersections and proximity of a nursing home.)

By 2020, traffic engineers calculated, the number of cars using Farmington would soar from 27,000 cars per day to 36,000, clogging traffic unless the five-lane intersection there — which hosts a 7-Eleven, an apartment complex, a senior living facility and a nursing home — were widened to seven traffic lanes. But after unsuccessfully casting about for years to find money for their “Farmington Road Improvement Project,” the city mothballed it.

Then a funny thing happened: nothing. There was no permanent traffic jam. Eleven years and two business cycles later, Farmington actually carries 700 fewer cars per day.

The seven-lane intersection, however, is back from the dead. The project, which also includes a new center lane further east on Farmington, newly striped bike lanes, a segment of sidewalk and a new signal and realignment of 142nd Avenue, is on track to be paid for by $21 million in Washington County property taxes.

Traffic engineers are still predicting (PDF) that traffic on Farmington is about to balloon: this time to 34,800 by 2035.

In a time when Portland-area residents frequently engage in hot debates over bicycling and walking improvements, this project is a reminder of the vast sums being spent in the region every day to speed up and increase the volume of automobile traffic at the expense of other modes and livability goals.

Literally.

“Mostly I see it as a lost opportunity for the community,” said Peter Welte, who lives three miles southwest of the site in Aloha. “They’re trying to make it faster to get from point A to point B, and in the process not making point B a place that you want to be.”

“They’re trying to make it faster to get from point A to point B, and in the process not making point B a place that you want to be.”

— Peter Welte, local resident

Abe Turki, the project manager, disagreed. “This is more than a $21 million turn lane project,” he wrote Thursday. “I believe it’s a balanced project that will add needed improvements to existing infrastructure.”

He noted that in addition to a continuous painted bike lane on Farmington, it’ll add street lighting and plant street trees to replace some of the ones the project will destroy nearby. The city will also make utility improvements, which are funded separately.

“This is an arterial road and a truck route, so it’s good for movement of vehicles and goods,” Turki said in an interview Thursday. “I think from the bike’s perspective, we’re adding two lanes that are not existing now.”

Welte, who said he often rides his own bike through the area, disagreed.

“For the type of rider that’s comfortable busting up to 30 mph and crossing a few lanes of car traffic to get to the turn lane, that’s fine,” Welte said Thursday. But though he said he can do it, he certainly doesn’t like to.

To prove the point, Welte, who sits on the Community Advisory Committee for Washington County’s Transportation System Plan update, has used what he says is the Federal Highway Administration’s official formula to calculate bicycle safety both before and after the project. Though the bike lane improves things somewhat, the extra lane change for bikes turning left off of Farmington eliminates that benefit.

“Really we’re just getting bike lanes because they have to, legally,” Welte said. As for the new sidewalk on the south side of Farmington, Welte (who also serves on the board of Oregon Walks) noted that the street already has an unfinished street-level path that’s used for walking and biking.

In 2008, 15-year-old Austin Miller was killed on the northwest corner of this intersection after he entered the Farmington roadway against a pedestrian signal after riding his bike south on the Murray sidewalk. At the time, BikePortland readers called this “a very scary place for cyclists.”

According to a recent traffic assessment, 15 percent of drivers on Farmington are already moving faster than 39 mph. The posted speed limit is 35 mph.

Turki, the project manager, said there’s “some truth” to the criticism that the previous traffic projections were wrong.

“The anticipated growth did not happen,” he said. “So the current study came up with lower numbers and we actually ended up adjusting the width of the intersection of Murray and Farmington to reflect those new numbers.”

“It’s not my specialty myself; I depend on traffic engineers and planners to get me those numbers,” Turki said.

For Welte, the problem is that city and county leaders aren’t asking the right questions of their staff and consultants.

“What they’re not doing is looking at all this empty space to the north of the project that’s sort of underutilized land between the project and TV Highway that might have some potential,” Welte said. “In other places, if you said, ‘We have $21 million to improve our community,’ they might think about how our transportation facilities could provide some kind of economic revitalization to nearby destinations.” Instead, Welte laments, he feels the County’s Major Streets Transportation Improvement Program (MSTIP, where the Farmington Road project comes from) focuses too much on widening roads and doesn’t consider how those projects may or may not support nearby small businesses.

Turki said the project had been discussed at “at least 11 meetings” of public outreach and planning back in 2001 to 2003 (PDF) that touched on issues including bike lanes, and that “the bike community” had been represented. The county says it’s not necessary to repeat that process, so the project is now in its final design phase. The next open house on the project is scheduled for January.