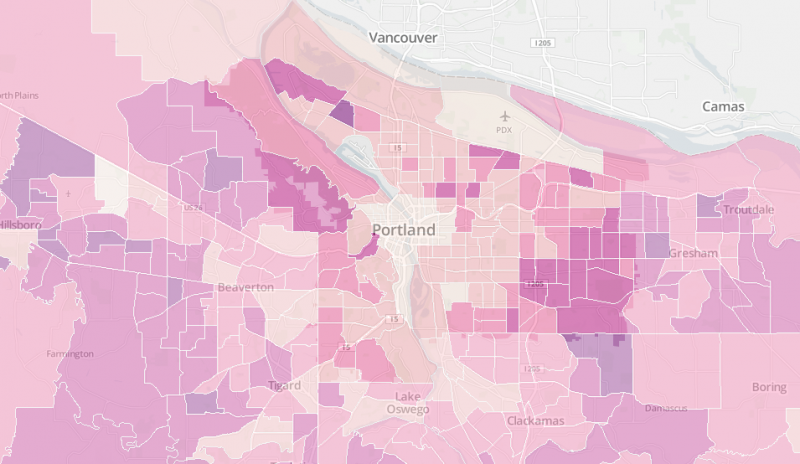

Forget the free bike map taped to your fridge. Forget the city’s terrific but frequently ignored 20-year bike plan. Forget the Bicycle Transportation Alliance’s map of its top 16 regional priorities, and even Metro’s long-term vision of a region with multiple urban centers and a huge grid of mass transit lines.

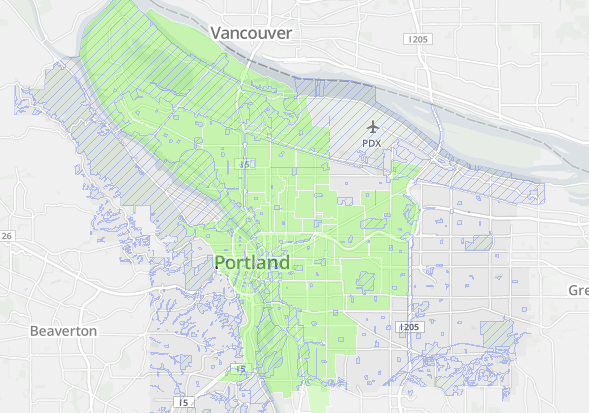

To understand the potential for where good urban transportation is currently within reach in Portland, you’ve got to look at the map above. Its green area shows “where the street grid meets connectivity standards and where the majority of the streets have sidewalks.”

Without a massive surge of political will, this is likely to be, for decades, the only area of Portland where most people will actually find it appealing to frequently get around without a car.

I don’t mean to say that biking, walking or skating is impossible or unpleasant in further-out neighborhoods. It’s not. And I’m not saying that efforts to improve things outside this area are useless. Just the opposite. But whatever the future brings, street connectivity is as close to destiny as things come in urban planning. It’s very, very hard to slice up private, developed land.

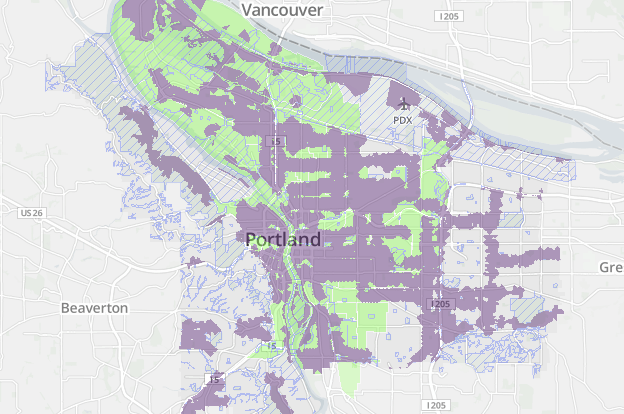

The new web mapping tool released this week by Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability is a revelation in part because it includes rarely-seen maps like this one. To show how important street connectivity is to the way a neighborhood works, here’s another: a map of connected neighborhoods in green, plus a map of everywhere in the city that’s currently within 1/4 mile of a “low-stress” bikeway such as a neighborhood greenway, buffered bike lane or off-street path.

It’s not that the city wouldn’t love to put neighborhood greenways all over Southwest and East Portland. But (despite substantial and much-needed recent investments) it hasn’t yet — because the grid isn’t connected. Maybe a person on foot can find a way through — but you can’t always do so, so it’s complicated. Which keeps people using cars, because who enjoys doing things that are complicated?

This isn’t just about biking. It’s about walking. And therefore it’s about transit, because every public transit trip starts and ends with a foot or bike trip, too. It’s hard to build transit ridership in neighborhoods where the only way to the bus stop is a crooked loop.

The need for more street connectivity is why Portland’s “Street by Street” effort to upgrade unpaved shoulders for use as low-quality footpaths exists. It’s also why crosswalks and connections through parks and schools are arguably more important to the East Portland in Motion plan than actual sidewalks are.

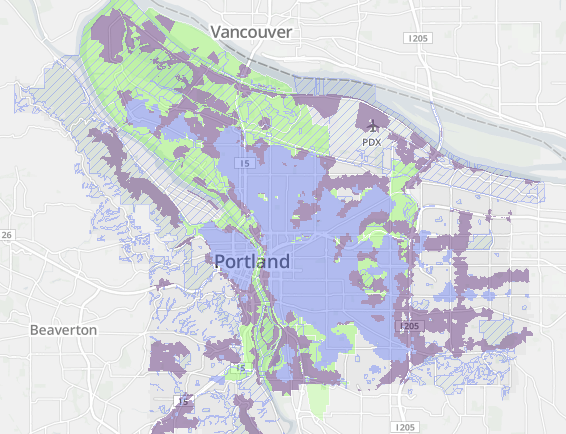

Finally, here’s another related map: one that combines the previous two maps with “places that are considered relatively complete on the 20-minute neighborhood index,” in blue. These are areas where people can live or work within walking distance of many of their regular needs.

It’s not a coincidence that these three maps are so similar. Areas that are well-connected and good for biking and walking are extremely desirable places to locate a business, because people like to spend time in them. They’re gushers of economic productivity; about 10 percent of all the property value in the entire state of Oregon sits inside the green and blue neighborhoods on this map. That’s not because the people who live and work there are inherently better than people in Bend, Medford or Sisters; it’s because these neighborhoods are built in such a way that they make valuable work possible.

Unfortunately, the fact is that since 1960 or so, we’ve been designing most new neighborhoods in a way that doesn’t make people’s most valuable work possible: we’ve been making them without connected street grids. Until those connections are finally built, the neighborhoods that don’t have them will continue to pay the price.

East Portland, Southwest Portland and the suburbs won’t be able to thrive until they’ve changed. But it’s going to be a harder job than any of us want to admit.