(Photo © J. Maus)

On September 29th, Portland City Council unanimously passed the 50s Bikeway plan, a series of safety improvements intended to make it easier to travel by bike between the neighborhoods of Rose City Park in the north and Woodstock in the south. I had been paying special attention to the process leading up to this vote because the bikeway’s proposed route goes right down my street, SE 52nd Avenue in the Mount Tabor Neighborhood.

“I don’t think it’s worth sacrificing the value of those urban places for the benefits urban freeways might provide, and I say that as someone who enjoys the convenience and speedy thrill of a freeway.”

There’s a lot to like about this neighborhood. It’s one of Portland’s classic streetcar suburbs, with an abundance of craftsman-style bungalows on quiet, tree-lined streets. Few enough cars pass by at slow enough speeds that older kids can play basketball in the intersection, and cats can saunter across the street at a leisurely pace. Within easy walking and biking distance of all this cozy livability — on the main commercial drags where the streetcars once ran — are some of the most inviting cafes, restaurants, and stores in town, along with food carts, banks, pharmacies, theaters, bike shops, a library, and other urban amenities.

The neighborhood benefits from being so easily traversed by muscle power. Residents can save a lot money by not having to drive so much, they’re healthier for doing so, and nearby businesses thrive on the foot and pedal-powered traffic. And of course walkability only adds to a neighborhood’s property values.

Ultimately I was sold on the 50s Bikeway and the benefits it would bring to this place; and it’s most certainly, quite strikingly better than another plan the city once had, which was to put a massive freeway right through the middle of it…

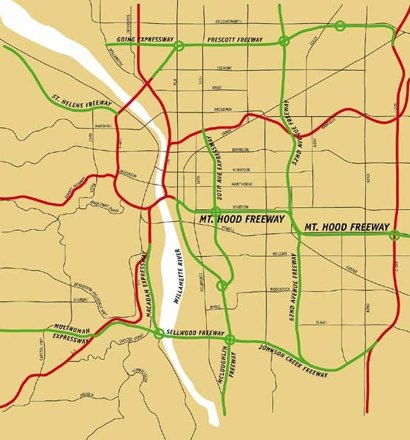

That was in 1966, when the Portland City Planning Commission proposed that a freeway be built along roughly the same route the 50s Bikeway will follow. This freeway was to have been part of a network of freeways that would have criss-crossed Portland.

Development Plan” map

from Portland Planning

Commission showing several

1 freeways that were never built.

I first encountered this nearly forgotten vision of our city’s future in The Portland that might have been, a post by Elly Blue on BikePortland in February 2009. (The map in that story was based on one that Matt Picio found, photographed, and made available here.)

A line on that map describes a freeway that would have snaked a course up along the lower 50s, and then along SE 49th, just a few blocks from my house. The line is labeled labeled: “52nd Avenue Freeway.”

I’m pretty sure this neighborhood wouldn’t be the inviting and thriving place it is today if there was a freeway running through it. The 52nd Avenue Freeway would have cut the quiet residential side of the neighborhood off from the bustling commercial strips on Hawthorne and Belmont. Pollution and noise would have been a constant presence. Many blocks of classic houses would have been bulldozed to make way for this freeway, and the value of the area — whether defined as property value, or the less quantifiable qualities that make a place livable — would have suffered.

The planners of the 1960’s, in trying to make Portland a better place in which to drive, would have made this and many other neighborhoods far worse places in which to live.

And they would have kept some great bikeways from ever having come into existence.

You can see on that old map that on and around NE Going Street — one of Portland’s best bike boulevards, where the stop signs were turned so that bikes can keep going and going at such a steady pace that it almost feels like a bicycle freeway — those Robert Moses-esque Portland planners of 1966 had proposed building the usual kind of freeway: a multi-lane ribbon of pavement they named the Prescott Freeway.

In the southeast part of the map, you can see how much of the land now devoted to the Springwater Corridor multi-use trail would have instead been consumed by something called the Johnson Creek Freeway.

And where SE Clinton, SE Division, and Ladds Addition are today some of the most pleasant neighborhoods in Portland, and are within easy biking distance of some of the most thriving local commercial centers in town (not to mention the SE Clinton bike boulevard), the Portland planners had back in the day decreed that a deep trench replace the blocks between Division and Clinton, and into this trench be poured the six lanes of the infamous Mt. Hood Freeway.

In the 1970’s neighborhood activists and local leaders managed to stop the Mt. Hood Freeway. They stopped it so near the start of its construction that there is an off-ramp to nowhere still hanging from an overpass over the east bank of the Willamette River, an off-ramp that was to have connected to the future freeway.

It was probably only because the Mt. Hood Freeway was stopped that none of those other freeways on the map got built. I feel an endless debt of gratitude to those neighborhood activists for having preserved what have come to be some of my favorite places in the world.

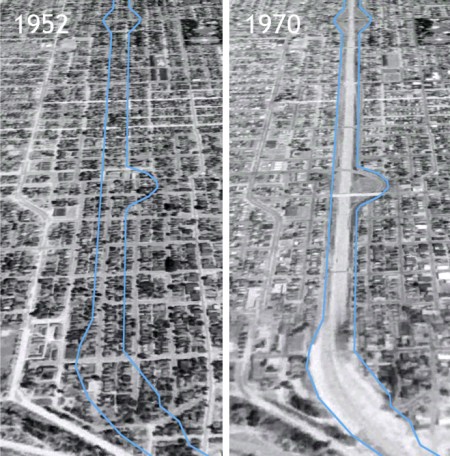

To get some idea what those activists helped save, you just have to look at what was lost. Like in this image,

(Image found via Google Earth)

It shows a before-and-after view of the part of North Portland that was consumed by the construction of I-5 in 1956. Everything within the blue line on the left was erased to make way for the freeway. This article in the Skanner community newspaper describes how the freeway paved, “right through hundreds of homes and storefronts, destroying more than 1,100 housing units in South Albina.”

It’s easy to lose sight of the value that gets lost in the course of plowing a freeway through a neighborhood, of ripping a path through the weave of urban fabric made up of many little routes between homes and businesses, and of how doing so disrupts the potential of that place to ever be anything but a conduit for loud and fast-moving traffic.

I don’t think it’s worth sacrificing the value of those urban places for the benefits urban freeways might provide, and I say that as someone who enjoys the convenience and speedy thrill of a freeway. Surface roads are more appropriate to a city, they don’t destroy neighborhoods, they’re cheaper, and within functioning urban places they can do the job of moving traffic well enough that freeways don’t need to be built.

This idea was recently taken up by The Economist:

“Highway construction generated some positive effects and some negative effects. We tend to focus on the positive effects and remark on how constrained the economy might have been without a highway boom. But absent a highway boom something would have been built and markets would have optimised to that something.”

It’s no great stretch to say Portland is better off with the somethings it built in the absence of the future freeways it had once planned.

— This article was written by Spencer Boomhower, whom you might recall as the man behind animated videos that explain the Idaho Stop Law and the Columbia River Crossing project.