— The author of this post has requested to be anonymous.

Last night while yet another person walking in Portland was killed by a person driving, the Oregon governor accomplished a personal priority, spending part of $20 million “to clear graffiti and litter along a beleaguered five-mile stretch of I-84” during an eight hour closure. Even if you also prefer the aesthetics of gray concrete underpasses, there’s an interesting twist: I-84 isn’t beleaguered by unsanctioned community murals, government neglect, or urban campers — it’s beleaguered by cars.

To experience this monumental transportation infrastructure without the normalized deadly threat of motor vehicles, I set out last night at the midnight closure, with a couple dozen intrepid explorers to ride I-84 by bicycle. Based on media reports of the civic emergency that necessitated this special intervention, I prepared mentally for what we might encounter.

The ride description said “Prepare for side streets, dirt paths, gravel and smooth pavement. Prepare to lift your bike and the bikes of others over things–if it comes to that. Prepare to go in the out way, and out the in way,” but my imagination embellished that further.

Compared to every bikeway I’ve ever been on, and most surface streets, I-84 was as clean as a whistle, and smooth as butter, before the cleanup even got started.

I imagined graffiti abatement armies feverishly spraying paint over every surface of this dirty stricken corridor, a dangerous work zone motorway strewn with barriers, disoriented evicted campers, and slick with gallons of fresh ‘ODOT Gray.’ I pictured crews marching oblivious across the highway hoisting sharp-edged replacement signage like slapstick comedy setups on a heavily-traveled cratered moonscape of ruts and potholes. I think I was expecting these things because they are like what I often experience on the bikeways of Portland, a maze of obstacles, glass-strewn and overgrown, where riders must be ever-vigilant to arrive safely at their destination.

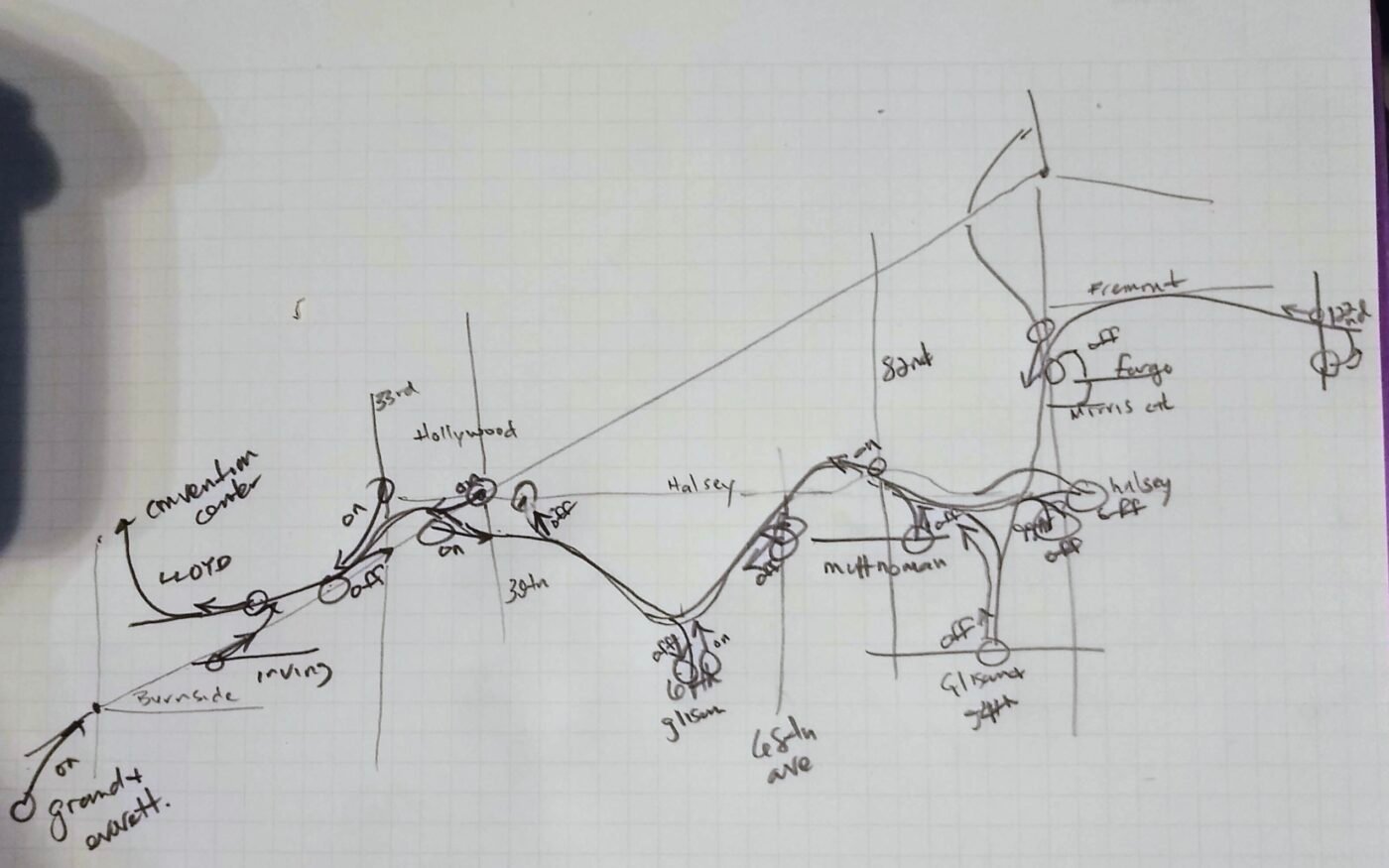

After a planning session over a hand-drawn map to determine the best access point, a steep embankment traverse, some off-camber singletrack over hobo trails, and a stealthy recon, a collective decision was made to “send it.” We lifted our bikes over the concrete barrier wall and pedaled west between the truck mounted attenuators and toward the river and the unknown. As we picked up speed under the half moon, and spread our wings across the generous and empty three-lane roadway, I experienced something new and surprising. We were freely gliding through the city — without any fear.

As a bicycle rider, you rarely get to have this experience. Bikeways in the US are designed to slow riders down, with chicanes, push-buttons, and ever-new safety interventions. Even separated bike paths are interrupted by debris, engineered obstacles, and increasingly by cars.

But I-84, the T.H. Banfield Expressway, is designed for going fast, and so we did. We quickly maxed out our gearing on the flat straightaways and banked turns, with the fixed-gear riders furiously spinning to keep up. Some turned off their lights to make our presence less pronounced, and because there were no defects to spot on the well-lit pavement.

Compared to every bikeway I’ve ever been on, and most surface streets, I-84 was as clean as a whistle, and smooth as butter, before the cleanup even got started. Were there colorful murals on the underpasses? I wouldn’t have noticed. We were busy enjoying the cool unpolluted night air, and the glorious quietude. There’s something about gliding through the city at high speed — in silence — that makes bicycling feel even more like you are flying.

Here’s something you can’t usually do while you are driving down a highway: have a conversation with other travelers. We talked about the exhilaration and the joy we were feeling, and how to experience it more often. “This is what we could have,” I said, thinking about Dutch bicycle highways. “This is what we already have,” was the reply.

Just like on our surface streets, it’s the cars that ruin our highways. Instead of spending millions painting the roses red, let’s give Oregonians an opportunity to enjoy the bed of roses under our feet.

We should prioritize building high-speed regional bicycle highways in Oregon, recognizing that e-bikes now enable fast climate-friendly long-distance travel for almost everyone. And we should certainly begin planning and construction of the Sullivan’s Gulch Trail along this central Portland corridor, a project that has sat neglected on the shelf for decades. But until those long-term projects are completed, we can better use what we already have. If we can close this busy roadway for a superficial painting party, we can easily close it periodically for everyone to experience a bicycle ride without fear.

Impossible you say? Perhaps you didn’t hear about Arroyo Fest last year. Car-obsessed Los Angeles closed seven miles of the 110 Freeway, one of the first freeways built in the US, for four hours last October for an open-streets event. It was a huge success with thousands turning out to enjoy the car-free route that in 1900 was an elevated wooden cycleway before it was converted to a freeway. You might have even gotten a taste of a car-free highway during Portland’s annual Bridge Pedal, and wondered how to have more events like this.

The Oregon Governor prioritized last night’s closure because there was a public perception that I-84 was too dirty and neglected to enjoy. But that perception was misplaced. Just like on our surface streets, it’s the cars that ruin our highways. Instead of spending millions painting the roses red, let’s give Oregonians an opportunity to enjoy the bed of roses under our feet. I-84 without cars is beautiful!