A team of local architects and planners think they’ve found a key that will unlock the door to more bicycling in Portland.

When we finally saw hard numbers about Portland’s cycling decline last spring, it was a reality check for many of us. 2023 counts from Portland’s transportation bureau aren’t ready yet, but other sources show that cycling in our city continues to lag behind not just our past numbers, but peer cities as well (more on that in a separate post).

Contrary to what we often hear from local transportation and elected officials, Portland hasn’t exactly “built it” when it comes to bike infrastructure. Yes, we can point to many projects and lane-miles of bike facilities; but none of that matters if the infrastructure isn’t good enough to entice people to use it.

My opinion piece on the decline last May spurred many conversations about what we should do to turn the ship around. For one group of local planners, it helped crystalize what they feel has been missing from the conversation: A next-generation type of bike infrastructure that could entice more Portlanders to ride.

Water cooler conversations tinged with frustration about the drop in cycling, led to an ambitious side project that mixed professional skills with personal passion and they came up with “An Urban Trails Network for Portland” — a concept for how we can claim more road space for active transportation, and reclaim our title as a great cycling city.

The team behind this vision is led by 52-year-old Mark Raggett, a 20-year veteran of the City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability who now works for a private urban design firm. He and three other co-workers — Nick Hodge, 28; Katie Barmore-McCollum, 35; and Ryan Al-Schamma, 27 — have spent months refining their idea and now it’s ready for public scrutiny.

I met with Raggett and Hodge back in June and then again last month and I’m very impressed with what they’ve done.

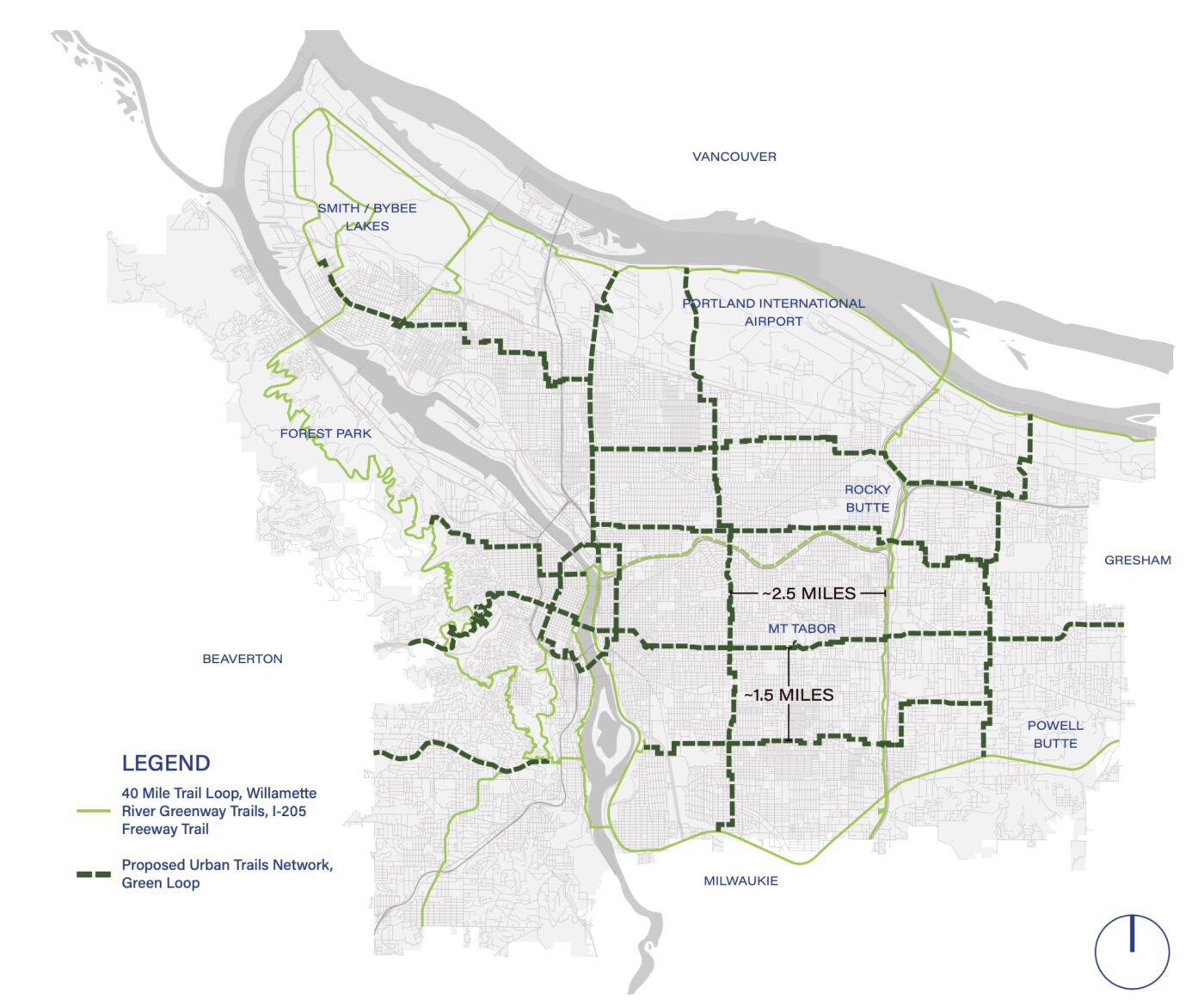

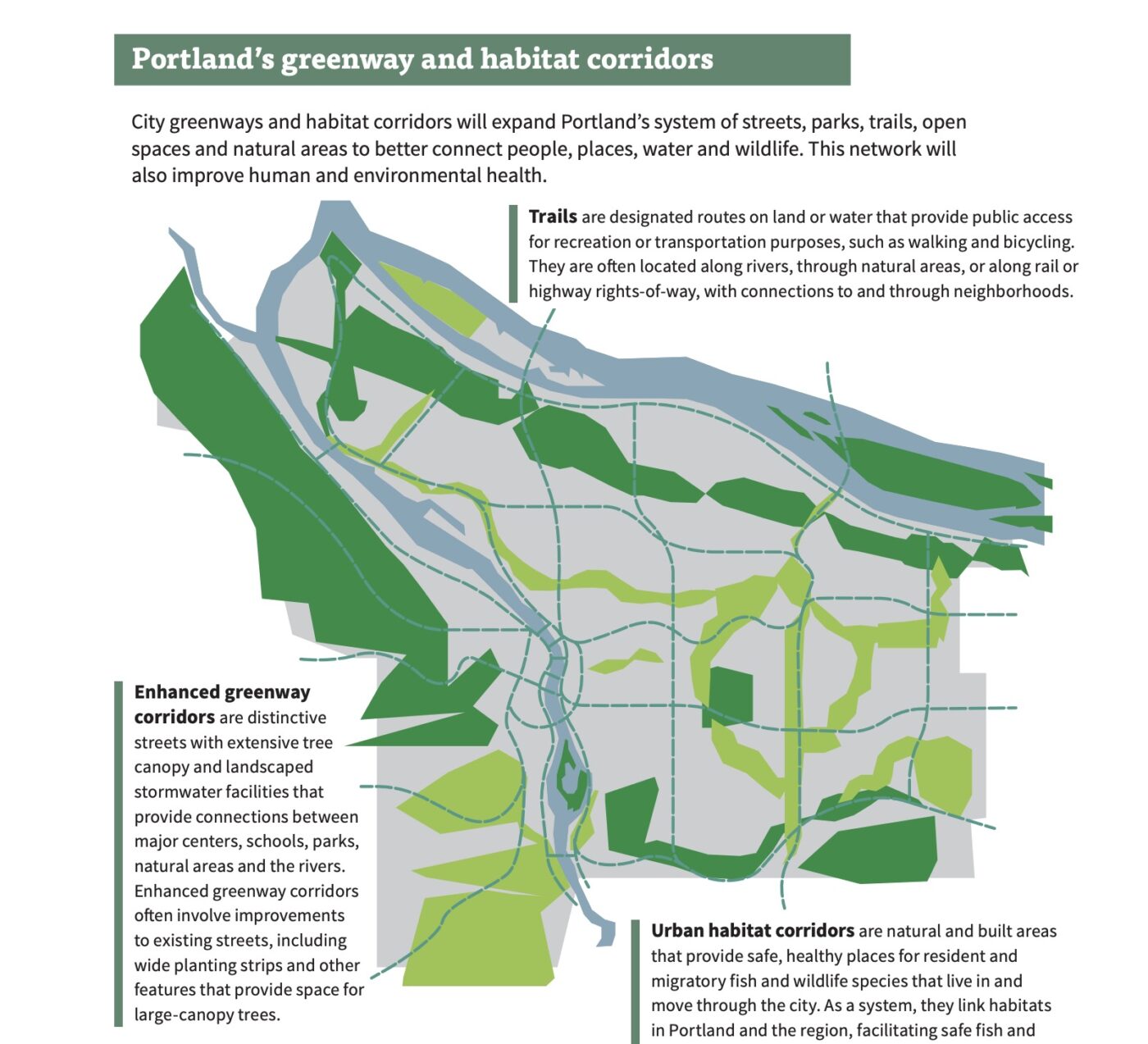

The Urban Trails Network is built on two pieces of existing policy: the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s neighborhood greenways, and the “city greenways” defined in Portland’s 2035 Comprehensive Plan (adopted in 2020). The network would create a backbone of residential streets with separated cycling facilities on them. Imagine the best elements of a multi-use path, mixed with the convenience and proximity to destinations of neighborhood greenways.

And the most interesting part? The new paths would be at sidewalk level and use existing right-of-way.

“We propose something new, that could be the ‘next generation’ of infrastructure, that would be more attractive in a low-density city like Portland to the large ‘interested but concerned’ crowd that may be driving more,” Raggett shared. And Hodge added, “Most people in the ‘interested but concerned’ category might not be aware of the greenways, or if they were, they might have a hard time finding and navigating them due to the lack of intuitive wayfinding tools.”

Raggett says the concept builds on the Comp Plan’s “city greenways” network, which is defined as, ” a system of distinctive pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly streets and trails, enhanced by lush tree canopy and landscaped stormwater facilities that support active living by expanding transportation and recreational opportunities and making it easier and more attractive to reach destinations across the city.”

Raggett, Hodge, Barmore-McCollum, and Al-Schamma have put together a nine-page presentation that lays out all the details.

The presentation shows how three types of existing residential streets could be retrofitted with the new Urban Trails Network design. In each type, they demonstrate how space for active transportation on the streets would grow. (The exact streets that would make up the network haven’t been named as this is still just a conceptual exercise.)

On a 36-foot wide street, for instance, the concept preserves 21-feet for car parking and driving (“the concept proposes a more pragmatic relationship with motor vehicles”), and would add a 15-foot, two-way cycling pathway and buffer strip on one side. On an street without sidewalks that has 60-feet of right-of-way but currently only 20-feet paved, the concept proposes a full rebuild that would include a 16-foot, two-way, shared bike/walk path on side and a sidewalk on the other. It would also add 18 feet for parking cars. On a narrow residential street with a 40-foot roadway, they propose adding a 12-foot, two-way path and buffer strip, while maintaining two lanes of on-street car parking and a 14-foot general travel lane that would be shared by both directions of drivers (a “queuing street” that is common on many narrow residential streets today).

With fewer people commuting to and from downtown, the idea is that better bikeways criss-crossing neighborhoods are more important than ever.

“The Urban Trails network will provide a much-needed and intuitive network of connections that will provide a flexible and resilient series of new pathways for all ages and abilities,” the presentation states. “Whether they be walking, rolling, riding, roller-skating or scooting around the city.”

Raggett and his team understand funding for this type of treatment is nonexistent. But they aren’t asking for money, they just think it’s time for Portland to move onto the next level of bike infrastructure and do something bold that will finally move the needle.

“The linked series of citywide pathways will define the next era of healthy, climate-responsive mobility in Portland.”

Take a look at the plan yourself and let us know what you think!