“Are our climate goals more important than assuring affordability in the city?”

– Rene Gonzalez, City Commissioner

Jonathan already primed the pump with his story this morning, so I’ll just jump right on in…

At the outset of Tuesday morning’s Portland City Council work session on housing production, Commissioner Carmen Rubio pointed out that “housing development is an incredibly complex topic.” Thankfully, bureau staff did an excellent job explaining the financial, economic and social issues that make it so.

But it took Commissioner Rene Gonzalez to charge full speed into the china shop with what he labeled a “provocative” question:

Are our climate goals more important than assuring affordability in the city? I’m not sure that is a place that policy makers have been willing to go in recent years. I think that’s a question that we have to ask ourselves at some point, and again, there are millions of tradeoffs in our code on a whole host of venerable policy goals that negatively impact construction cost and therefore affordability. I put that out more rhetorically and provocatively.

And yes, bike parking came up several times.

For several months, the bureaus — Planning and Sustainability, Development Services, Housing, and Prosper Portland — have studied how to boost housing production. As part of that work, the Bureau of Development Services surveyed developers and others involved in the permitting process to learn what they viewed as key impediments to quick housing production. BikePortland reported in February that respondents across the board—developers, city employees and other professionals—reported bike parking as a key cause of delayed housing production.

At Tuesday’s work session, Matt Fairris, of BAE Urban Economics, a consulting group working with the city, presented findings about the cost of various local regulations. He explained that the current bike parking regulations add 3 to 6% to a project cost, or about $11,000 per unit.

Given that System Development Charges (which the city collects to offset the impacts of the new development on, for example, sewers, transportation, and parks) are 3-7% of project costs, and that requirements for ground floor active use are only 1-4% of project costs, the costs of bike parking are, as Commissioner Mingus Mapps put it, “a surprising result.”

Mapps asked for more detail about that expense. Fairris explained that in most of the city the developer has to build 1.5 bike parking spaces per unit. If they are only building above ground, that means a big room at ground level for bike parking—a room which could have been another residential unit or retail. Working with the city, Fairris’s group calculated how the volume of that room would shrink if you reduced it from 1.5 to 1, or even 0, spaces per unit, and what the value would be if that footage were generating revenue. From there they calculated a cost.

Mapps responded that “As your PBOT guy, one of my goals is to facilitate people getting out of their cars and on to bikes, so this is a space that I want to think about, and I look forward to working with my colleagues on council to figure out how to bring affordable housing whilst meeting our climate goals.”

The cost of public infrastructure, like bike lanes and sidewalks was also noted, with uncertainty around requirements being a problem.

Gonzalez picked up on that with a question, “Where are the specific areas of uncertainty that were identified. Because that sounded like it was a significant item. Biking requirements? I’m just trying to get a handle on that.”

Fairris responded:

It really is sort of the gamut. Unfortunately there is just a lot of uncertainty around road infrastructure — sometimes you have to upgrade the sewer, sometimes you have to do bike parking. You thought the entrance to your property could be here, but instead it has to be around the corner because of a bike lane. Again, all of this well-intentioned but it has kind of an impact on what improvements have to be made in order to get that development through the permitting process. So I would say from a cost perspective, digging up a road and upgrading a sewer is probably is one of the biggest things we can ask … Having some certainty from the beginning is probably more critical than anything else.

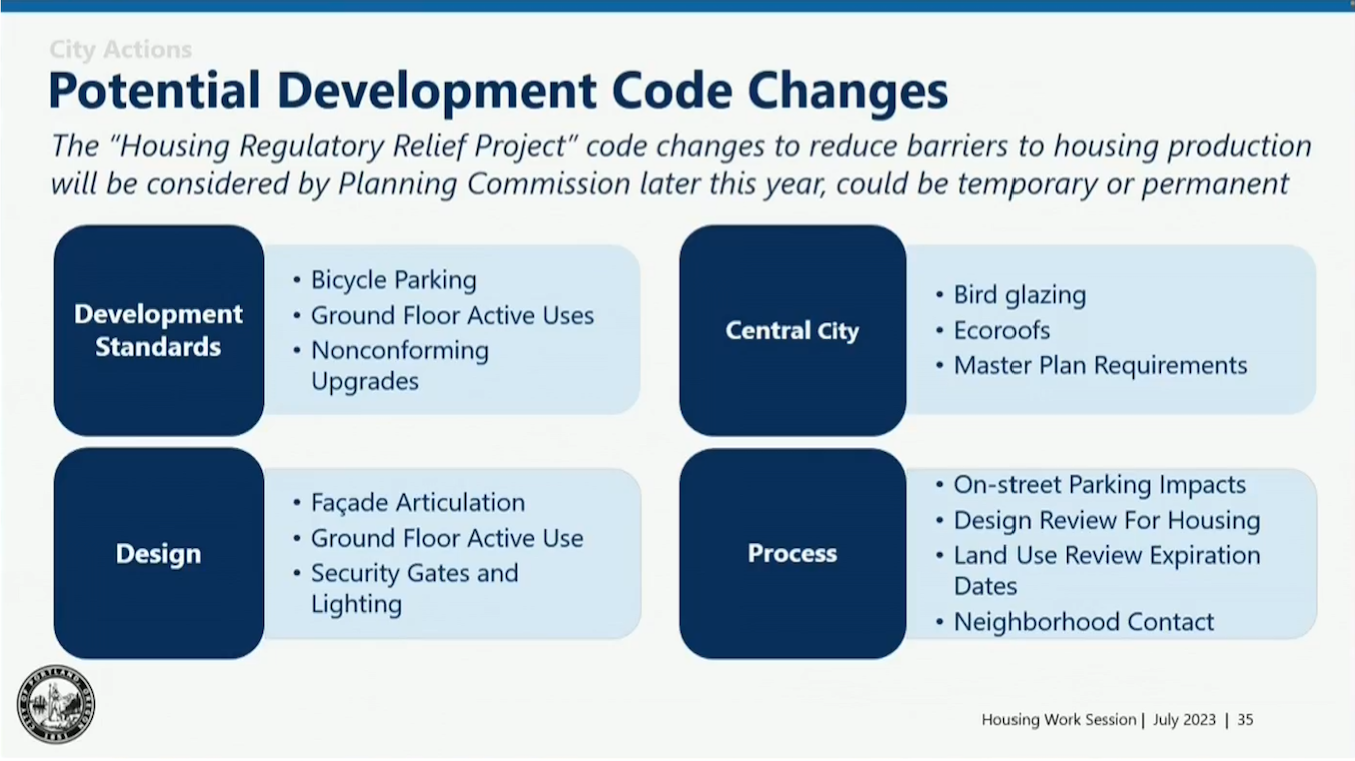

The session also delved into Inclusionary Housing, the finance of developing affordable housing, including project feasibility, permitting reform, cleaning up redundant and conflicting city code, and Portland’s future housing needs. Reports on those topics can be found online at Commissioner Rubio’s website. It is clear that this council has committed to a lot of house-cleaning, and it seems like they are putting everything on the table, particularly in preparation for the charter reform reorganization.

In the end, council seems poised to loosen regulations in the name of making housing more affordable — even climate change fighting-minded ones like bike parking. An important piece of context here is that as bike parking mandates have gotten stronger, Portland has, as of last month, eliminated all auto parking mandates. And if the debate is about cost, the price to provide car spaces and garages is vastly higher than providing space for bikes. That means developers have a strong incentive to reduce auto use, regardless of the bike parking code.

Former Portland planning commissioner and one of the architects of the 2019 bike parking code update, Chris Smith, doesn’t want people to take the wrong message away from Rubio’s proposals and their impact on housing affordability. “I would guess that developers are spending several multiples more on auto parking than on bike parking,” he told BikePortland after today’s work session. “And I get that building a bike room might cost more, but cycling is a transportation affordability measure. The payout to get around on a bike is a huge affordability benefit for tenants in the long run.”

Since it was just a work session, the Council did not take any votes. But in the coming weeks and months expect recommendations and actions on housing production strategies and development code changes to work their way onto city council agendas. Videos of the session can be reached here.