How do you maintain a stranglehold on what type of streets an entire state can design? Find wealthy business owners with direct access to decision-makers, create an opaque bureaucratic framework you can exploit to make sure you have oversight of every major project, then make your own rules, overstep your authority and scare agency staffers into going along with you.

That’s a recipe we have some experience with in Portland and the same situation has played out on the statewide level for nearly two decades.

Following years of concerns from inside and outside the agency, the Oregon Department of Transportation’s top brass has finally responded to a formal complaint about how one advisory committee dominated by freight industry representatives has wielded undue influence over projects throughout the state — often at the expense of pedestrian and bicycle safety.

All about the MAC

ODOT’s Mobility Advisory Committee (MAC) was formed in 2003 as a forum for stakeholders to share feedback with ODOT staff about how state highway projects impact drivers (freight and auto), and to sign off on major work zone and detour plans. The group was also meant to offer input on Oregon Revised Statute (ORS) 366.215, which states that the Transportation Commission, “may not permanently reduce the vehicle-carrying capacity of an identified freight route when altering, relocating, changing or realigning a state highway unless safety or access considerations require the reduction.”

But over the years, the committee’s influence grew way beyond what lawmakers intended. With the encouragement of ODOT leadership, who issued a directive requiring the freight industry be included in agency discussions of roundabouts and other projects in 2012, the MAC became dominated by freight industry business owners and advocates. What started as a forum for ODOT staff to learn how projects might impact truckers had become a de facto decision-making body with veto power over the design of projects.

In 2012 freight interests within the MAC tried to amend ORS 366.215 so that it would apply to all ODOT projects, not just those on “identified freight routes.” Thankfully, due in part to pushback from The Street Trust, that effort failed.

In response to that attempted power-grab, Oregon passed an Administrative Rule in 2013 to create a legally-binding “Stakeholder Forum” where discussions about ORS 366.215 could take place with a broader set of representatives. But without proper oversight or transparent processes in place, the MAC remained a powerful committee that has had a chilling effect on ODOT staff and project design that remains to this day.

The most important statute you’ve probably never heard of

Decisions about “reduction in vehicle carrying capacity” as outlined in ORS 366.215 are very consequential. The law was meant to ensure that changes to street designs and lane striping don’t have an excessively negative impact on freight traffic. The statute requires state planners and engineers to take into account any reduction in vertical or horizontal width of a roadway cross-section — a.k.a. the “hole-in-the-air.” Here’s how ODOT describes the concept in their latest implementation guide:

Although not in rule, the term “hole-in-the-air” describes the area needed to accommodate legal and permitted over-dimension loads. The hole-in-the-air refers to the entire roadway, not just the load on the road at any particular moment. We need to think of a reduction in vehicle-carrying capacity the same way the freight stakeholders do – if they can get through the highway segment today, they want to get through there tomorrow.

That means every time ODOT wants to narrow a general travel lane to add bike lanes or curb extensions, or other features on a major state highway and freight route, they have to share their plans with the MAC. In a healthy agency culture, ODOT staff could listen to MAC input and weight it among other factors like the need to improve safety for other road users.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it works at ODOT because a large majority of MAC members, and the agency staff and leadership that have enabled them for years, believe roadway space is a zero-sum game where freight truck needs should always come out on top.

Why the MAC is wack

It wasn’t until the Oregon Secretary of State audited ODOT in 2020 that these problems with the MAC became public.

The audit found that the MAC’s power had grown considerably in the decade between its creation in 2003 and the establishment of the Stakeholder Forum in 2013. The Stakeholder Forum was supposed to mitigate the MAC’s influence (it was launched, the audit said, “in response to concerns voiced by bicycle advocates that the agency was relying heavily on non-technical feedback from freight stakeholders to make decisions about highway capacity”), but instead, the MAC subsumed it.

“While the MAC started as a series of informal meetings,” the Secretary of State wrote in the audit, “… internal ODOT documents indicate that the MAC is now considered the base stakeholder group for the Stakeholder Forum. MAC members are also the only identified members of the Stakeholder Forum.”

This was especially problematic because the audit also found that the MAC was made up mostly of people from the freight industry and that, “other key stakeholder groups had not been actively encouraged.” At the time of the audit, there was no bicycle or pedestrian representative on the committee, despite the existing Administrative Rule that requires it.

And auditors learned that it wasn’t just the safety of bicycle riders and walkers these freight reps were putting in jeopardy. The MAC would also request changes to projects and work zone traffic control plans that, “may be inherently riskier for workers than what was initially proposed.”

What makes the role of the MAC even more galling is that there is no ODOT agency policy, statute, or rule, that gives them this broad authority. But, as the audit found, “internal ODOT policy” requires staff to get their sign-off on project designs. “This essentially grants the MAC ‘go or no go’ decision-making authority over state transportation projects, despite lacking legal and formal standing,” the audit found:

This has reportedly led to long delays and to decisions being made on some projects that emphasize mobility over safety. Staff also said that committee decisions are rarely, if ever, overruled by ODOT leadership.

In the end, the Oregon Secretary of State decided more work was needed to make sure feedback from the MAC is, “appropriately balanced with the professional expertise of ODOT designers, engineers, and consultants, and does not negatively impact worker or transportation user safety.”

Despite nearly two years since the audit was published, the MAC and its members continue to have an unfair, outsized influence on transportation projects.

“When I started this job, I wondered, ‘Why do they have all this power?’ and it was like, ‘Oh, they’ve got legislators in their back pocket.”

– ODOT staffer

How the process works (or doesn’t)

BikePortland has been contacted by several ODOT staffers in the past 12 months. They all wanted to raise a red flag about the conduct of the MAC and its deleterious impacts on safety projects — especially those within urban areas.

One person said they disagreed with the MAC’s opposition to their project, but worried about job security if they didn’t go along with what the committee wanted. “There’s always this fear that MAC members will run to their legislators,” the person said, who requested anonymity due to fear of backlash. “When I started this job, I wondered, ‘Why do they have all this power?’ and it was like, ‘Oh, they’ve got legislators in their back pocket.”

You don’t have to go far into MAC meeting minutes to find an example of the source behind these concerns. I randomly clicked on the March 2022 minutes and found a presentation about an intersection project in Banks, just yards from the popular Banks-Vernonia State Park Trailhead.

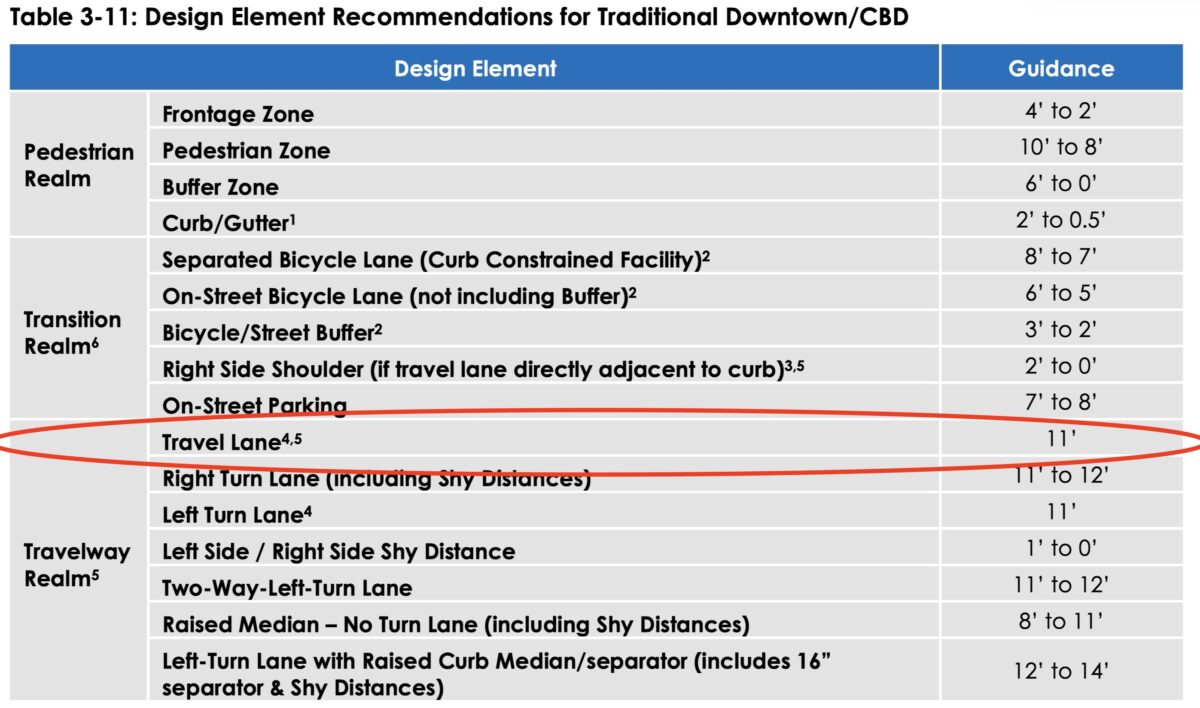

The project is to change the intersection of Highway 47 and Banks Road to make it safer and better equipped to handle growth in the area. The ODOT staffer who presented it to the MAC and sought their approval explained the intention to narrow both of the main travel lanes from 13-feet to 11-feet wide.

The ODOT staffer said the 11-foot lanes would make room for a median divider and four-foot shoulders (there are no bike lanes here, but there’s a high volume of riders due to proximity of the state trail route), but he immediately ran into objections from MAC Member Steve Bates, president of Seattle-based trucking company V Van Dyke, Inc. Bates said he wanted 12-foot lanes and ODOT should narrow the shoulder to just three feet.

MAC Member Nick Meltzer, who represents bicycle riders, said he’d prefer to maintain the four-foot shoulder, “and if a truck needed the extra width, it could just hang over the paint line,” he said (according to meeting minutes).

The Oregon Trucking Association rep also wanted 12-foot lanes and proposed trimming six inches from the buffer and another six from the median to get the extra foot.

Bates then added that if the narrow shoulder isn’t a bike lane, bike riders should take the lane and share with other highway users. That’s a preposterous suggestion, given the speed and size of trucks (many of them notoriously dangerous logging trucks) that regularly drive on Highway 47 and the Banks-Vernonia is a magnet for riders of all ages and abilities. At this point, ODOT Region 2 Active Transportation Liaison Jenna Berman spoke up in support of 11-foot lanes, saying it’s a downtown area and ODOT’s design guidance says they should be 11-feet. “We know there are cyclists out there, and whether they are in the lane or on the side… if those cyclists get hit at a slower speed, they will be less severely injured,” Berman said. “This is why we are looking to narrow the travel lanes, because they help to control speeds… even if there is room for 12-foot travel lanes.”

A vote was taken at the end of the meeting (even though it’s non-binding since the MAC has no voting authority), and the project was opposed 4-1. That means staff had to go back to the drawing board and the intended safety changes will be delayed. The project isn’t on the MAC agenda again until November — eight months later.

This process has happened numerous times. ODOT sources we talked to for this story say even if the MAC is amenable, sometimes ODOT upper leadership won’t have their back and will side with the MAC for wider lanes or other freight-centric designs.

The Oregon Administrative Rules state that if a proposal cannot be agreed to by the MAC and ODOT, it should come to the Oregon Transportation Commission for a final decision. One ODOT source we interviewed for this story said they’ve heard MAC members boast about how no projects have ever had to go to the OTC. “From my point of view internally,” our source shared. “The reason why they never go to the OTC is because we roll over because the group has always had so much power!” The staffer said the MAC has such an influence that some engineers and planners have been “brainwashed” and are known to change elements of a project proactively to make sure it gets past the committee.

It’s all about lane widths

Most of the tension between the MAC and ODOT staff revolves around lane widths (and to a lesser extent, roundabouts, which are often contentious). Freight interests push for lanes to be at least 12-feet wide, if not more (ODOT leadership once claimed they needed 19-foot wide lanes on the St. Johns Bridge), while ODOT staff often push for narrower lanes in order to reduce speeding and improve safety. ODOT staff also say their own Blueprint for Urban Design (PDF), adopted in 2020, clearly states that 11-foot lanes are preferred to 12-foot lanes in business districts.

Staff are trying to implement what their own rules recommend, and they still get rejected by the MAC. And the width of bike lanes are often a sticking point, despite the OAR that governs 366.215 clearly stating, “Street markings such as bike lane striping or on street parking are not considered a reduction of vehicle-carrying capacity.”

To help break the logjam over lane widths, ODOT has held two work group sessions with their Safety and Mobility Policy Advisory Committee (a committee with no bike or pedestrian representation and one I didn’t even know existed until I worked on this story). The work session involved 10 freight industry reps and three ODOT engineering staffers, including State Traffic Engineer Mike Kimlinger.

Kimlinger asked the group for their thoughts on 11-foot travel lanes.

Steve Bates said ODOT should not even consider 11-foot lanes in any new construction project. Trucking company COO Erik Zander said ODOT’s guidelines should remove bicycle lanes entirely from “main highways” so that 12-foot lanes can be maintained. Oregon Trucking Association President Jana Jarvis also spoke against 11-foot lanes. “When you provide bicyclists with 6 feet of width and freight with 11-feet of width, there is no equality in the conversation,” Jarvis said, according to ODOT meeting minutes. “She said she hopes that ODOT would value freight to the point where we would have very few of these discussions about reducing travel lane widths.” To add heft to her comments, Jarvis also suggested that freight industry demands should be weighed heavily in these conversations because they “pay for the system.”

Disagreements remain, but change might be coming

On July 26th, 2022 the Interim Chair of the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (OBPAC), Emma Newman, wrote a letter to ODOT Director Kris Strickler and other top ODOT brass. It included scathing critiques of the MAC:

“The MAC is holding up important complete streets projects that have strong community support. This includes projects that will save lives and reduce serious injuries when they are built and are designed using approved ODOT standards… The delay of these projects is counter to the safety, health, and economic values of the State. Some of these delays are lasting 3-6 months in the planning and design phases, which can then trigger even further overall project delivery delays. The MAC is interfering with ODOT’s duty to serve Oregonians… This is harmful to ODOT’s mission and the public interest, especially while pedestrian fatalities continue to increase in Oregon.”

Newman blasted the committee for its lack of transparency and its chilling effect on staff and project designs. She requested that OBPAC be notified of project changes that would negatively impact bicycling or walking and she asked for a high-level meeting between OBPAC and MAC members, and ODOT staff.

Nearly two months later, on September 21st, Newman got a reply. Strickler said he’d set up an executive meeting in early October with top ODOT staff and a separate meeting with committee members.

Newman spoke about the letter at the OBPAC meeting yesterday. “I think we’re getting traction in ways that we haven’t up until now,” she said.

Newman seemed skeptical that anything would change. So do we. Until someone outside of ODOT cares about this enough to do something about it, we’ll be stuck on the side of the road.