Its aim is to make sure every voter has some influence, in proportion to the popularity of their choices.

You know an issue is hot when you go to a Labor Day weekend party and people are talking about it. The issue is Ranked Choice Voting (RCV), and it will be on the ballot this November as part of the Charter Reform referendum to reorganize city government.

More precisely, voters will be voting on a specific type of RCV called Single Transferable Vote (STV).

As BikePortland previously reported, the Portland Charter Commission has proposed a package of changes to voting and city governance after grappling for a year and a half with how to improve the way we run our city.

I wanted to better understand how the STV method was implemented, and I have a hunch that some BikePortland readers would also like to take a deeper dive. So if you are someone who isn’t satisfied until you understand the details, I’ve pulled together a wonkish explanation of STV, and how the method could give bicycling concerns more voice in city government.

The Big Picture

It helps to think of the opinions and candidate preferences of voters as a big conglomeration of information. A good voting method extracts as much of that information as possible so that the candidates we put in office best reflect what voters want.

Ranked choice, single transferable vote is a nuanced way of extracting information about voter preference. Its aim is to make sure every voter has some influence, in proportion to the popularity of their choices. In this way, the fullness of your opinions is captured, even when your first choice is for a candidate who has no chance of winning, or alternatively, who is sure to win.

I don’t understand that 25% bit

On the ballot this fall is RCV with STV in multi-member districts. That means you will rank candidates who are running in your geographical district. The city will be divided into four districts, with three candidates elected to council from each one.

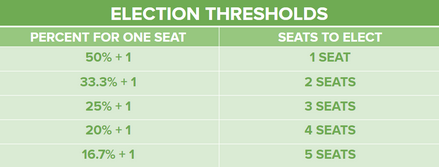

The arithmetic of having three winners is that each candidate will need to capture over 25% of the total vote in their district. Let’s walk through that.

If you have a voting system with only one winner (N = 1)—like we do now—that candidate will have to capture one more than 100 divided by (N+1) votes to win. That comes to 100 divided by 2, or 50% of the vote. That’s what we are used to.

With two winners, N = 2, it becomes 100 divided by 3, or 33% of the vote. Three winners is 100 divided by 4, to arrive at the 25% from the method proposed on our ballot (see table above).

Another way to think about it is that the threshold is set so that it is mathematically possible for only N candidates to get enough votes to win. That’s just the arithmetic of voting.

Here is how tabulating the vote works

This is the fun part. And honestly, there is a short YouTube video from Minneapolis Public Radio which does a fantastic job of explaining tabulation in only 2 minutes and 42 seconds using colored sticky notes, dry erase markers and hands. Their explanation is delightful and will satisfy most people.

Here goes my explanation, it’s a little less delightful, but is tailored to being a cyclist in Portland.

The first pass of vote counting is similar to what we are used to—count how many first choice votes each candidate got.

It’s the next steps that differ. Any candidate who passes the 25% threshold is a winner. But how far did they make it beyond the threshold? We are accustomed to declaring elections “landslides” and talking about “mandates” according to how how strong a win is, so the next step—the actual transfer of votes—might take some thought to get used to.

Any win above 25% has “surplus” or extra votes beyond what is needed to win. It is the number of surplus votes a winning candidate receives that will be transferred to other candidates, in proportion to the votes each candidate received as the second-ranked choice of those winning voters.

In other words, the second-ranked choice of all the voters of a first-pass winning candidate are counted and the fraction of the total vote each candidate got is calculated. Those fractional proportions are then multiplied into the number of surplus votes and distributed to other candidates proportionally.

Why it matters for bicycling

I might have lost you in the previous paragraph, so let’s talk bicycles. Let’s say there is an election, and the big issues are police reform, law and order, and renter protection. Under our current system of winner-take-all voting, improving active transportation infrastructure—better bike facilities—can’t break through those hot-button issues.

But under RCV STV you might get a candidate, call her Catherine, who advocates for better bike infrastructure. It’s her main issue. She gets 10% of the vote on the first round. Candidate Joan, who is an incumbent and whose main issue has always been police reform gets 50% of the vote, so she has a surplus of 25% of the district vote. She’s a winner.

Let’s distribute Joan’s 25% surplus votes to other candidates. Looking at the 2nd-ranked choice of Joan’s voters, we see that a whopping 50% of them chose Catherine. Half of a 25% surplus is 12.5% so Catherine’s total vote count becomes 22.5%—the bike advocate has got a shot at winning!

There is a third candidate, Pascal, who is the law and order candidate. He wins with 30% of the vote, or a 5% surplus. Let’s redistribute that surplus. It turns out that 60% of Pascal’s voters chose Catherine as their 2nd choice candidate. That’s 3% of the total district vote which gets added to Catherine’s column, and she too is now a winner with 25.5% of the vote!

And that is how issues which have trouble breaking through to become a “hot-button” number one issue, but which nevertheless have strong community support, can gain representation on the City Council. These are called “minority” positions. I point this out because this is distinct from positions held by racial or ethnic minority voters, and there is a tendency to conflate the two.

The takeaway

Importantly, the process does not lose ranking information. Both Joan and Pascal will know that a large percentage of their voters want better bike facilities, and you might end up with the two of them—opposites on the police issue—supporting Catherine as she pushes bike issues on council.

Moreover, because a candidate might be angling to be the 2nd or 3rd choice of a competitor’s voters, they would be wise to avoid running a campaign that angers those voters who are not ranking them as 1st choice.

Finally, RCV STV does away with primaries. Historically, the turnout for primaries is low, which means that a small percentage of highly motivated voters determines the selection of candidates that the larger voting public will see in the general election.

Not quite done

Of course, there is more to STV than my explanation covers. The process may make several passes through the data, reaching 3rd- and 4th-choice candidates, and beyond. Also, there are methods for eliminating the bottom scoring candidates when it becomes mathematically impossible for them to win. Their lower-ranked voter choices then percolate up to candidates who can still feasibly win.

This video, also out of Minneapolis, goes into greater technical detail about STV starting at minute 20:51. I don’t know what software Portland will be using to tabulate votes if charter reform passes this fall, so there might be differences in details, but the Minneapolis video gives a good general explanation of the methods and addresses some of the “what ifs” that come up.

Got other questions or observations about charter reform? Let us know in the comments.