“Cities have shown they have the capacity and resources to quickly adapt to new crises. These adaptations need to prioritize vulnerable communities and underserved areas.”

According to a report by the City of Portland released last year, 19 out of the 27 people killed in a traffic crash while walking on Portland’s streets last year were experiencing homelessness. This is 70% of the total number of pedestrians killed, and about a third of the total people killed in car crashes of any kind.

The staggering statistic sent shock waves through Portland. Mayor Ted Wheeler’s solution was to declare a state of emergency and ban camping at so-called ‘Inherently Dangerous Camping Locations,’ which include streets on PBOT’s High Crash Network and along state and federal highways.

But homeless and transportation advocates said the move could cause additional trauma by uprooting people and further criminalizing homelessness while not doing anything to solve the root of the problem.

That’s where a team of six students who call themselves Street Perspective at Portland State University’s Master of Urban and Regional Planning (MURP) program stepped in with a planning and research project titled, Safety Interventions for Houseless Pedestrians. Angie Martinez, Meisha Whyte, Asif Haque, Nick Meusch, Peter Domine, and Sean Doyle presented their findings at last week’s Friday Transportation Seminar hosted by PSU’s Transportation Research and Education Center.

This study focused mainly on the transportation policy lens, but also looked at potential housing and shelter solutions.

There are many potential reasons why homeless people are at increased risk of being killed on the streets, but a main factor is they choose to set up campsites near highway ramps and along arterials. The large, vegetated buffer zones around freeways are perfect for pitching tents and arterial streets are often near services, stores, and other destinations. Unfortunately they’re often near many high-speed drivers.

The Street Perspective team talked to people living on the street and service providers who work on the ground. They mapped out conditions after making site visits. They crunched data on collisions.

One of their main takeaways was how harmful sweeps in these environments can be. Presenters pointed out how forcing people to relocate to areas where car traffic is calmer may mean cutting them off from services they rely on and communities they’ve built.

“Many of the negative effects that come from harassment and sweeping are due to this loss of community that provides people with some sense of stability and connection,” Sean Doyle, one of the Street Perspective students, said during the presentation.

So, what tactics do the Street Perspective students indicate could work to help keep people experiencing homelessness safe from traffic violence? Here’s a recap of their ‘promising practices.’

Safe Streets for All

At the beginning of the pandemic, PBOT enacted the Safe Streets Initiative and installed traffic calming measures on certain streets to give people more room to walk, bike and roll while social distancing and staying safe from car traffic. The Street Perspective team suggests PBOT tackle the traffic violence unhoused people face by applying similar measures to areas near essential resources where campsites are set up.

“Cities have shown they have the capacity and resources to quickly adapt to new crises. These adaptations need to prioritize vulnerable communities and underserved areas,” the presentation said.

Infrastructure

Active transportation investments would not necessarily need to specifically target homeless people — as anyone who walks or bikes in an area would benefit from safer infrastructure — but these investments could be prioritized in places where homeless people are disproportionately impacted.

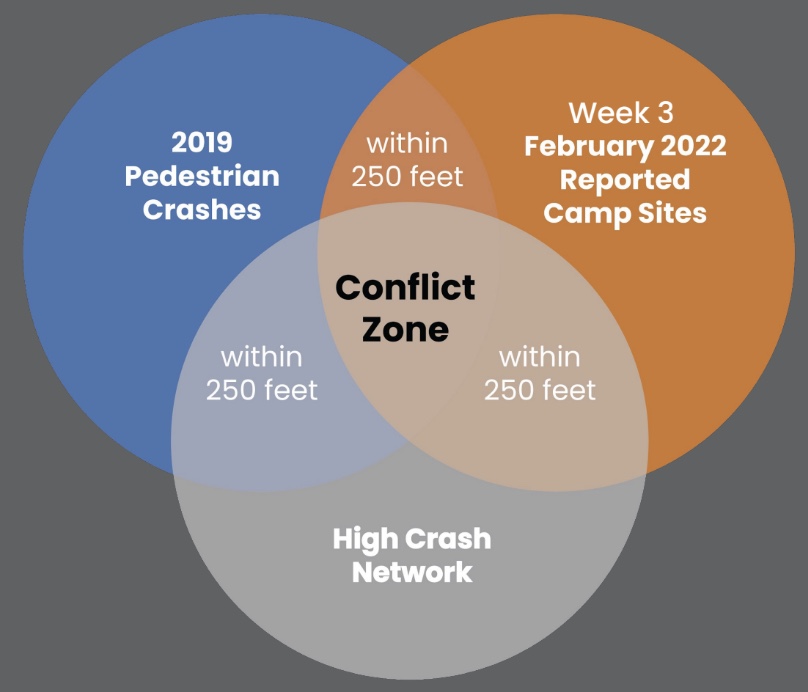

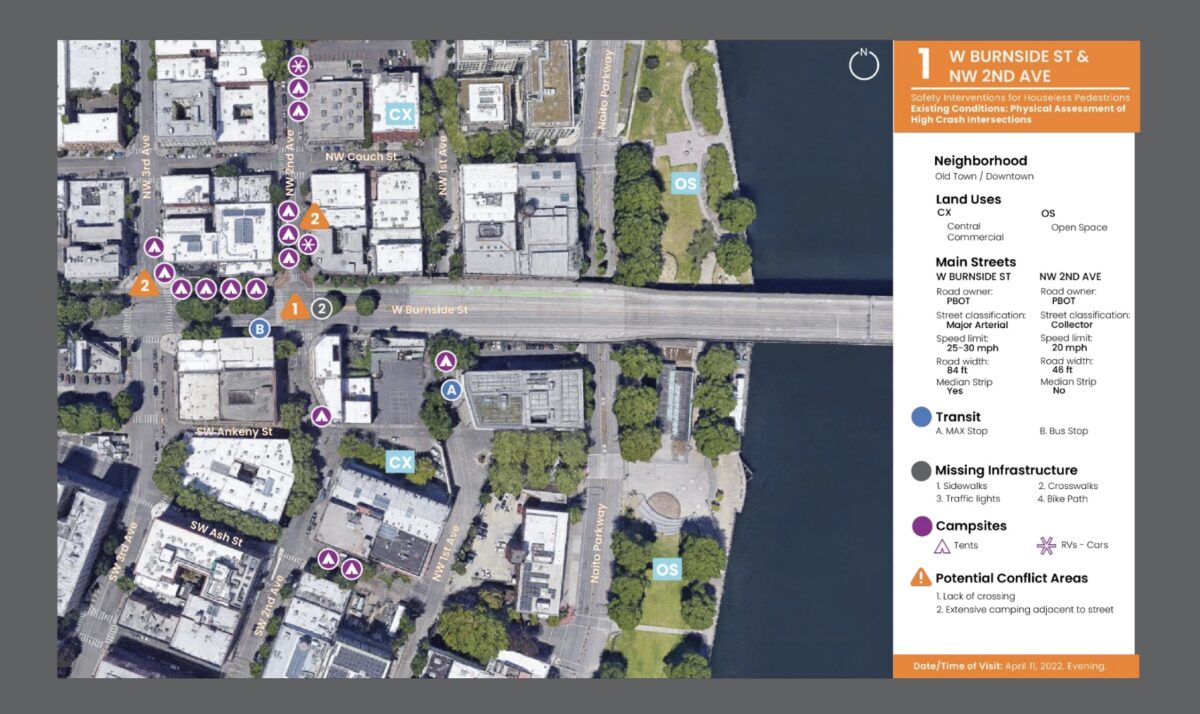

The Street Perspective study looked at three intersections in Portland (above) located in proximity to homeless campsites where pedestrian injuries have occured (all three are on the PBOT High Crash Network): W Burnside St and NW 2nd Ave; NE Sandy St, NE Halsey St, and NE Cesar Chavez Blvd; and NE Glisan St and NE 122nd Ave.

While the specifics vary, the study reported that they all have inadequate crossings, missing sidewalks and cater to people driving cars at the detriment of everyone else.

The types of improvements the Street Perspective team suggests be made to these dangerous intersections are the same treatments PBOT has done at other intersections around the city, such as enhanced street lighting, improved crosswalk visibility and speed reduction measures. The students suggest a more broad implementation would provide one long-term solution to the unsafe conditions homeless people face on our streets that is more effective than simply moving people away from the dangerous intersection without doing anything to fix the problem.

Better and More Shelters

While the Street Perspective students say sweeping campsites is not a helpful long or short-term solution to the crises our unhoused neighbors face, that does not mean it is ideal to have people living next to high crash corridors. But homeless people are not a monolith, and will have different wants and needs for their future housing. There are potential steps the city could take to prevent fatalities while giving people a choice about where they want to live. This could include: providing places for car and RV camping, which provide more security compared to being unsheltered on the street (and which PBOT Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty has already made progress on); sanctioned campsites in safer locations; or tiny home villages and motel vouchers.

The students provide a more extensive list of proposed solutions in the full presentation which is available via YouTube. They also acknowledge the limitations of their work because it mainly focuses on transportation infrastructure. In order to see real changes, this crisis will need to be tackled holistically.

“There is no single solution. Infrastructure alone cannot reduce speeds,” one presenter said. “Traffic safety is intertwined with shelter and necessities.”

Correction: We initially referred to the MURP students as ‘researchers,’ when some of the work the Street Perspective team should instead be characterized as ‘planning.’ We have changed the language appropriately.

We also reported that pedestrian fatalities had occurred at the sites the students chose to study. This was an error – these sites were chosen based on crashes occurring within 250 feet of a campsite resulting in pedestrian injury, not necessarily fatality. We regret any confusion this may have caused.