How can a city encourage affordable housing residents to use transit and shared bikes and scooters more often? Results from an ongoing Portland Bureau of Transportation pilot program and a new report from Portland State University suggest one way to do it: make it free.

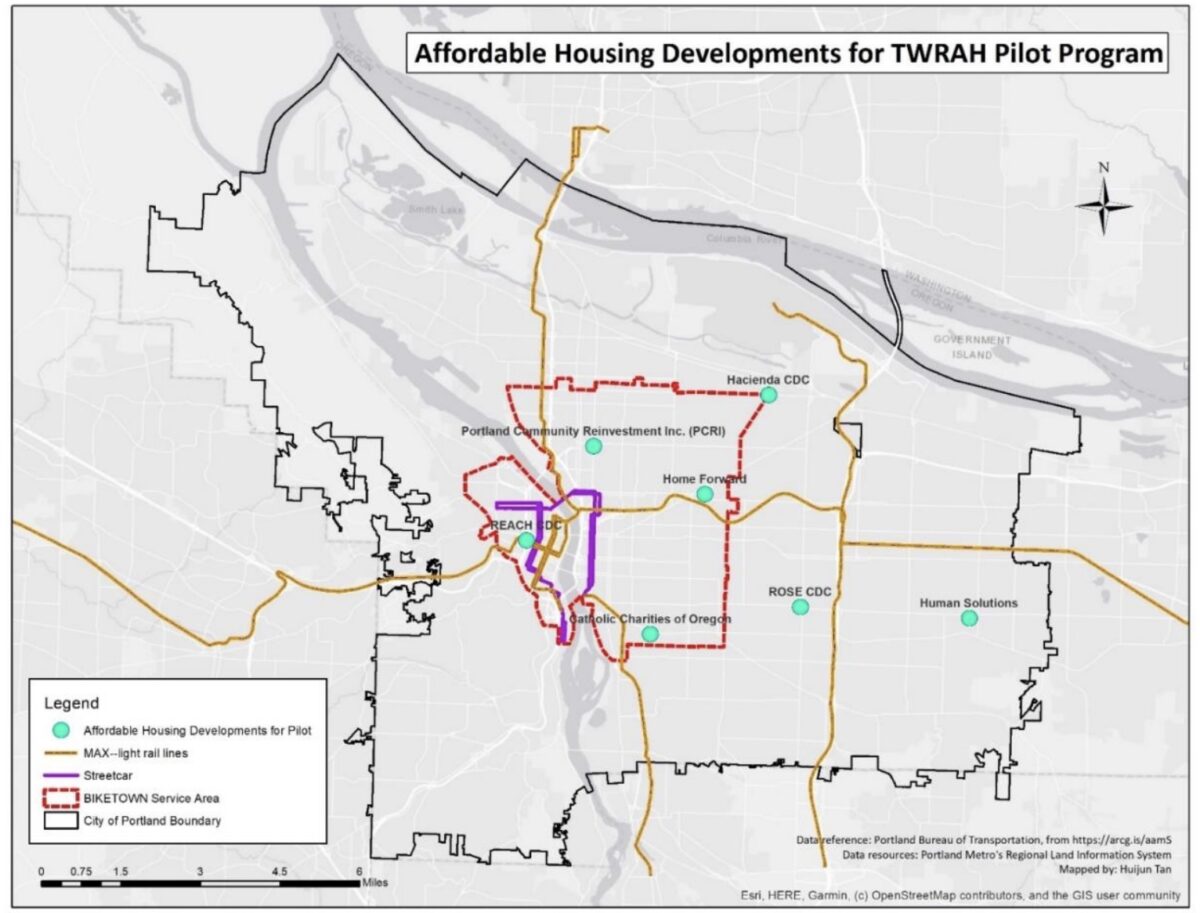

Since PBOT’s Transportation Wallet for Residents of Affordable Housing (TWRAH) pilot program launched in 2019, hundreds of residents of affordable housing across Portland have tested the hypothesis that removing cost barriers is a crucial way to make our transportation system more equitable. Now the program has been further validated by a new, federally-funded report from the Transportation Research and Education Center at Portland State University.

Other cities across the U.S. have implemented similar programs, and the idea of “universal basic mobility” (UBM) has recently become a hot topic. A 2018 Bloomberg CityLab article suggests that “the right to freedom of movement…[is] not merely a human right, it’s the foundation of a healthy democracy.” Not only would access to a basic level of mobility improve one’s individual quality of life, the UBM framework suggests, it’s also instrumental in creating less car-dependent places with healthier communities and thriving economies.

The TWRAH pilot is now in its second phase. The first phase, which ran from late summer 2019 to early 2020, provided 500 people living in affordable housing with a prepaid Visa card loaded with $308 — the price of an annual TriMet reduced fare pass — to spend on transit of their choosing, including TriMet, e-scooters, Biketown and ride-hail services like Uber and Lyft.

Advertisement

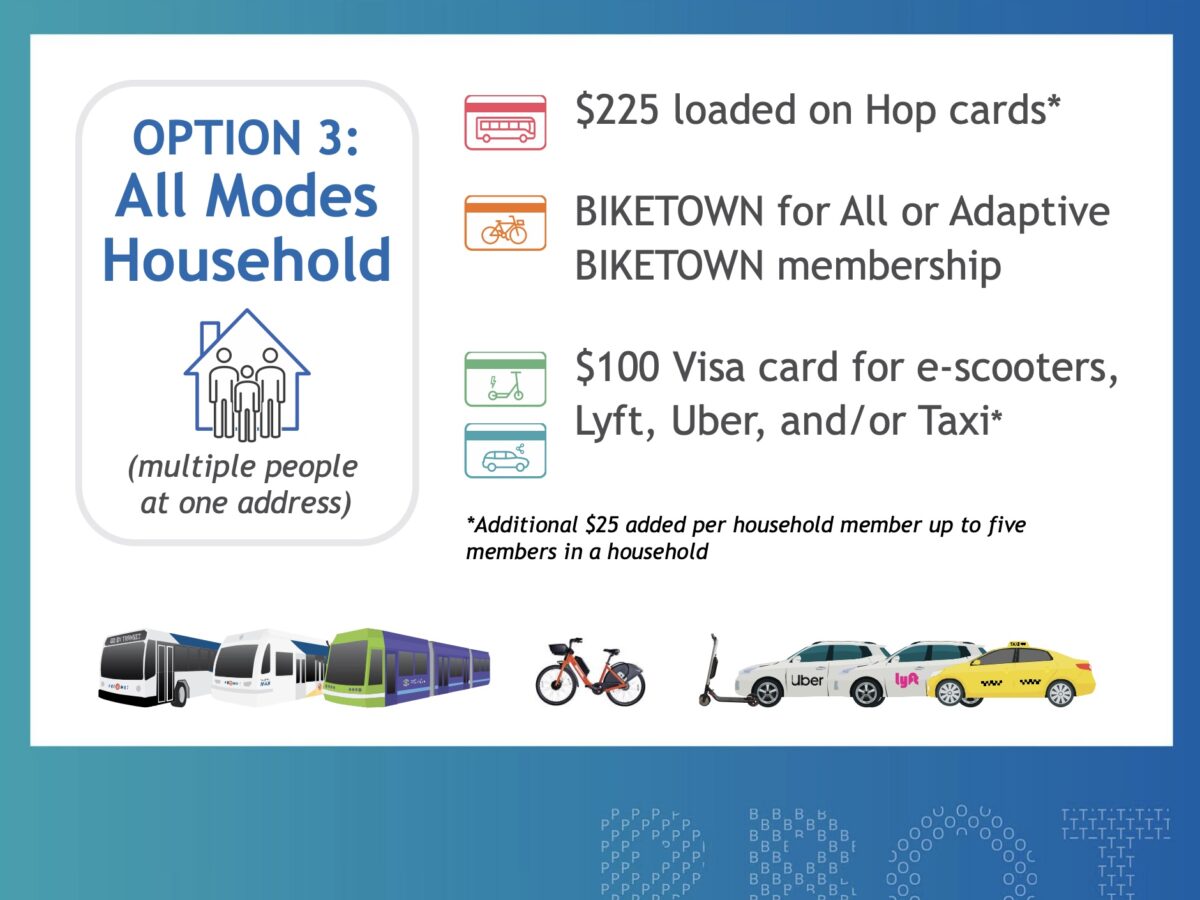

The second phase of this pilot program, which began in late summer 2021 and is ongoing, provides people with more opportunities to cater the Transportation Wallet plan to their needs, whether they want to explore riding e-scooters, Biketown bikes or stick to TriMet. The program has also expanded to accommodate multi-person households, encouraging each member of a family or household to use the transit offered.

The TWRAH pilot isn’t the first time the city of Portland has experimented with a subsidized model to incentivize people to get around without cars. This pilot was modeled on PBOT’s original Transportation Wallet program, which began in 2017 to provide people who frequent some of Portland’s most car-congested areas the opportunity to access significantly reduced rates for non-driving modes.

Through this original Transportation Wallet program, people who live or work in Portland’s Northwest or Central Eastside Industrial Parking Districts can access reduced rates for TriMet, Portland streetcar and Biketown. All it takes is $99 — or trading in your annual parking permit — to receive almost $700 to spend on non-car transportation.

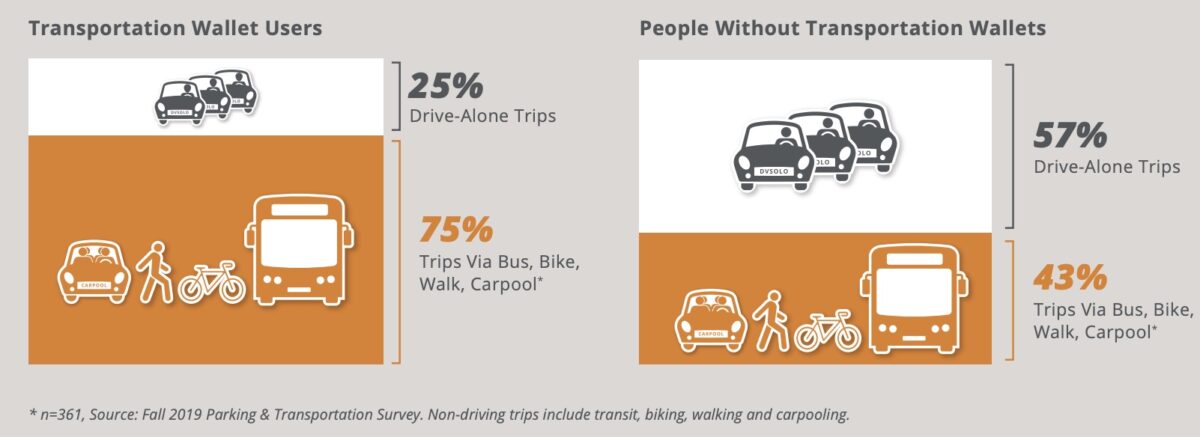

According to PBOT data (PDF), there were 4,000 Transportation Wallets in circulation from September 2017 to November 2019, 60% of which were received in exchange for annual parking permits. Almost a third of PBOT survey respondents said they drive less as a result of this program.

Along with simply providing funding, TWRAH project managers at PBOT say it has also been important to eliminate other barriers that might prevent people from utilizing new methods of transportation, like how to find and use an e-scooter or bike share bike.

“The TWRAH funds ended up being a totally fungible source of income… The money that would’ve gone toward transportation could go to something else.”

— Nathan McNeil, TREC at PSU

Both Transportation Wallet programs aim to encourage people to expand their transportation options. But Nathan McNeil, one of the PSU researchers who evaluated the first phase of the TWRAH pilot, points out that most of the participants in the program directed toward residents of affordable housing were already using public transit. 71% of the TWRAH participants interviewed in the PSU evaluation didn’t have a vehicle to begin with, and many were using TriMet already.

For them, having their mobility subsidized was a source of stress-relief, giving them a little more room in their budget: 32% of the participants surveyed in the PSU study said the best thing about the transportation wallet was money-related.

“The TWRAH funds ended up being a totally fungible source of income that helped out people’s bottom lines,” McNeil says. “The money that would’ve gone toward transportation could go to something else.”

The ability to use the Transportation Wallet funds to subsidize existing TriMet usage is an important part of the program. But the majority of participants surveyed in the PSU report said they did try to use different modes of transportation that they wouldn’t have used otherwise — an insight that shows the importance of funding and educational outreach.

Skeptics of universal basic mobility need only look to the people anonymously quoted in the PSU study for reasons why everyone deserves the ability to get around easily. And car sympathizers should hurry to find an explanation for why owning an expensive motorized vehicle provides more freedom and independence than owning a subsidized transit card.

“I can go wherever I want without [thinking about] where I will get the money to ride the bus or the train,” one participant said.

Incentive Program for Residents of Affordable

Housing in Portland, OR, by TREC at PSU)

It’s also clear, however, that more big-picture work will have to be done so people can ditch cars entirely. Three of the seven affordable housing providers PBOT worked with on phase one of this study are located in east Portland, which doesn’t have adequate e-scooter and bike share coverage yet, and isn’t as dense with TriMet options, either. 69% of East Portland residents used ride hail services more than once, a figure that drops down to 44% for people living elsewhere.

Still, mass transit and micromobility advocates shouldn’t worry that a few free Uber rides will make people scoff at car-alternatives. 83% of east Portlanders in the study said they used TriMet more than once, and 63% said they took mass transit more than 15 times. One study participant — whose residence location is unknown — talks about ride hail and cab services more as an occasional treat than a trusty transportation standby, saying it was “nice to have cab fare for rainy days, emotional days and for animal appointments.”

PBOT officials say the future of this program is yet to be determined, and more information will be available after the second phase of the pilot is completed in 2022. As it stands however, the program appears to be one effective way to identify barriers that prevent people from being as mobile and low-car as they’d like to be.