(Photos: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Nerdy educational rides are the unsung heroes of Pedalpalooza, Portland’s three-month festival of free bike rides that’s going on now through the end of August. They don’t get nearly as much attention as the massively crowded (and fun!) party rides; but those who seek them out are often rewarded with insights and trivia-laden tidbits that add depth and meaning to the places we ride through.

Sunday’s Train History Ride was a great example. Led by two noted Portland authors and historians — Shawn Granton and Dan Haneckow — the ride retraced the route of the St. Johns Motor Line, a steam train that was the first mass transit to serve the Peninsula. Launched in 1889 and in service until 1903 (after which it was electrified), this train carried passengers from the lower Albina neighborhood to St. Johns via Commercial, Killingsworth, Greeley, Lombard, and Fessenden streets. Along the way it had a major impact on how north Portland grew into the early 20th century.

The ride was organized by Granton, a noted illustrator, founder of Urban Adventure League and author of the incomparable Zinester’s Guide to Portland. The ride itself was led by Haneckow, whom you might know from his excellent Cafe Unknown blog or his book, Portland Then and Now.

Haneckow has been fascinated by urban history since he was a child in a Navy family that moved throughout the U.S. At Sunday’s ride he shared with me that it was Portland’s rich streetcar history that first attracted him to the subject locally.

The St. Johns Motor Line caught Haneckow’s eye because it was a precursor to electric streetcars and ran a route through relatively undeveloped land north of the bustling downtown and central eastside neighborhoods. It was the first mass transit line to offer workers in north Portland neighborhoods a way to reach jobs in the Albina railyards and grain ports along the downtown riverfront. It began service just over a decade after Albina, Portland, and East Portland residents voted to consolidate into one city in 1891. Albina was by far the smallest (population-wise) of the three former cities, but it’s large geographic footprint made real estate speculators and city leaders salivate with the promise of new housing and urban developments — and more taxpayers to fund further growth.

Advertisement

Steam was chosen as a propulsion method, Haneckow explained, because it was cheaper to get up-and-running than an electrified line. The lack of established hamlets and towns on the northern peninsula meant that the St. Johns Motor Line needed to provide a lower-cost alternative that could be upgraded later as population and commercial development increased.

At the start of the ride, about two dozen transportation history buffs circled around Haneckow in the parking lot of McMenamin’s White Eagle Pub on North Albina and Russell, where the Motor Line began. From there we headed east and then north. (The original route used Commercial Avenue, but several blocks of it are now underneath Legacy Emanuel Hospital.) From Commercial, the route went west on Killingsworth, then north at Greeley. We could see the train’s lasting influence on the urban form at the intersection of Killingsworth and Greeley where the existing commercial building (Mio Sushi) is curved to accommodate the train’s wide turning radius. At that same intersection, Haneckow pointed out a still-in-use traffic pole in front of a 7-Eleven (pictured) that was first installed for use by the electric bus line that replaced the steam train.

At stops along the way Haneckow helped us imagine the Portland that existed a century ago — like a real-life version of his popular “Then and Now” book. In a Walgreens parking lot at Lombard and Peninsular, we learned we were standing on what used to be known as Downtown Peninsular, a small hamlet that developed around the train stop. In the beautiful, wooded Columbia Park, Haneckow shared a photo of the former Portsmouth Station. As we made our way onto Fessenden (which today serves the #4 TriMet Bus Line and has been a continuous transit route for well over 100 years), we stopped at the end of the line. “There used to be an amusement park in what was known as Cedar Park,” Haneckow shared, pointing a few blocks over.

These little tidbits were my favorite part of the ride. Like when the owner of a 1901 Victorian on Willamette Blvd came out to share with us that the original owner was a former civic engineer for the City of Portland who was responsible for paving the street he lived on. Or when Haneckow shared that much of the Willamette Riverfront between Albina and the central eastside was formerly a slough that was filled in with ballast from European tankers who came to Portland to fill up with grain. That ballast included everything from rocks, sawdust, and even furniture and other unwanted trash from Europe. Portland’s original free pile! (On a serious note, that fill is also why some streets and buildings on the eastside are settling unevenly.)

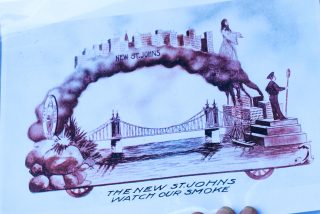

Much like urban rail advocates boast today, backers of the St. Johns Motor Line saw it as much more than just a train. The rails carried hopes and dreams of a bigger, grander city, full of bustling commercial nodes and vibrant neighborhoods. In fact, as Haneckow explained, St. Johns’ civic leaders once saw themselves as the rightful center of Portland. At our final stop on the ride, Haneckow shared an illustration of a float (right) that ran in a local parade in the early 1900s. It featured a Jesus figure, the St. Johns Bridge, smoke from industrial buildings, a Manhattan-like skyline, and a swagger-infused tagline that read “The New St. Johns – Watch Our Smoke.”

If you love Portland history and want to have a deeper understanding of the places you ride through, I highly recommend looking out for rides like this.

Tonight (7/12) Granton will lead his classic Dead Freeways Ride which will ponder what Portland would have been like if we actually built all the freeways once planned. (For more on this ride, read this profile from The Portland Mercury in 2009.)

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.