(Source: Portland Bureau of Planning & Sustainability)

“When you drive by today you might not even realize there’s a neighborhood there.”

— Kevin Bond, City of Portland BPS

The City of Portland is working to restore a neighborhood that was systematically destroyed by car-centric highway projects, misguided urban renewal plans, and racism-fueled redlining. And I’m not talking about the Albina district in north Portland. I’m talking about an area of south Portland between I-405 and the Ross Island Bridge.

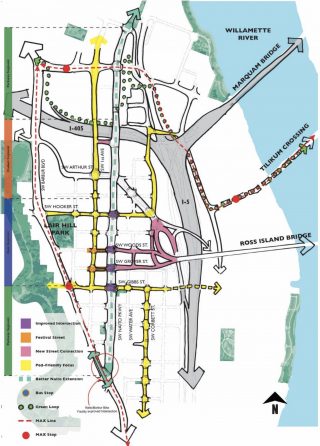

The Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) is working with the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS) on an ambitious project to recreate the street grid in the Lair Hill and Corbett areas of the South Portland neighborhood. Once the plan is implemented, new streets and redeveloped parcels will include multi-story commercial and residential buildings, complete sidewalk networks and protected bike lanes. Put another way, the project would extend Better Naito to Barbur Boulevard.

(Source: City of Portland)

Project managers from both agencies shared an update on the projects in a meeting Tuesday night.

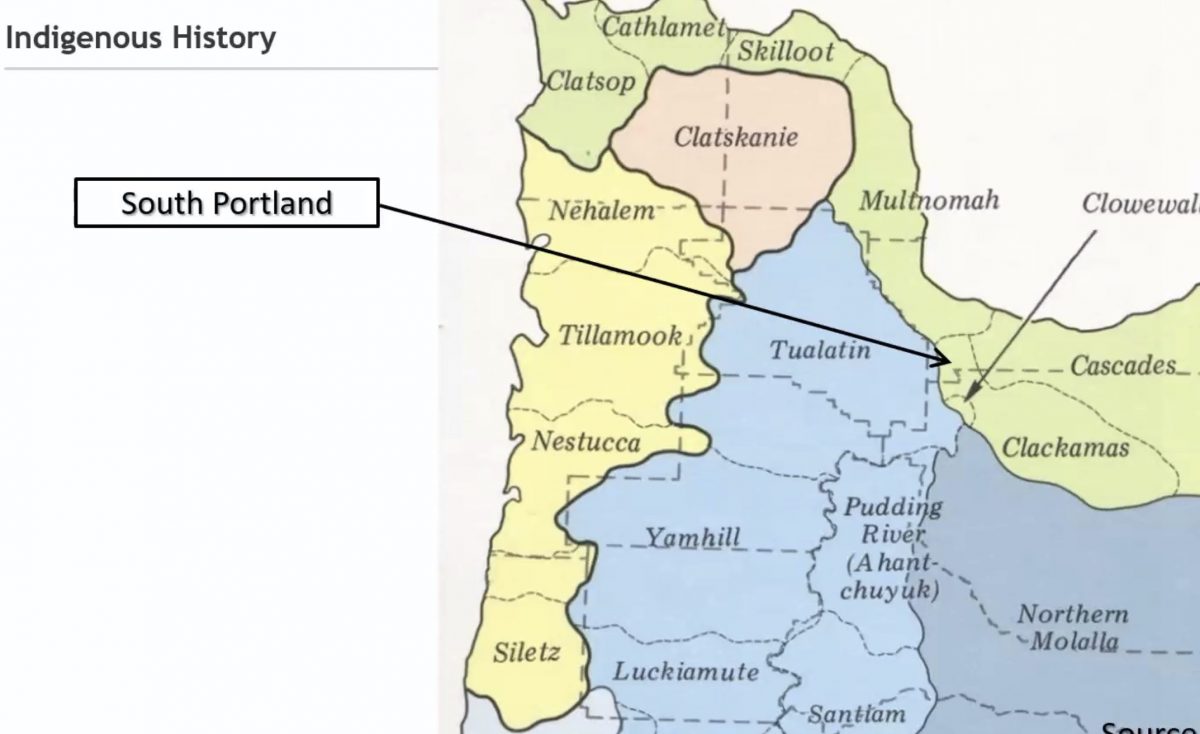

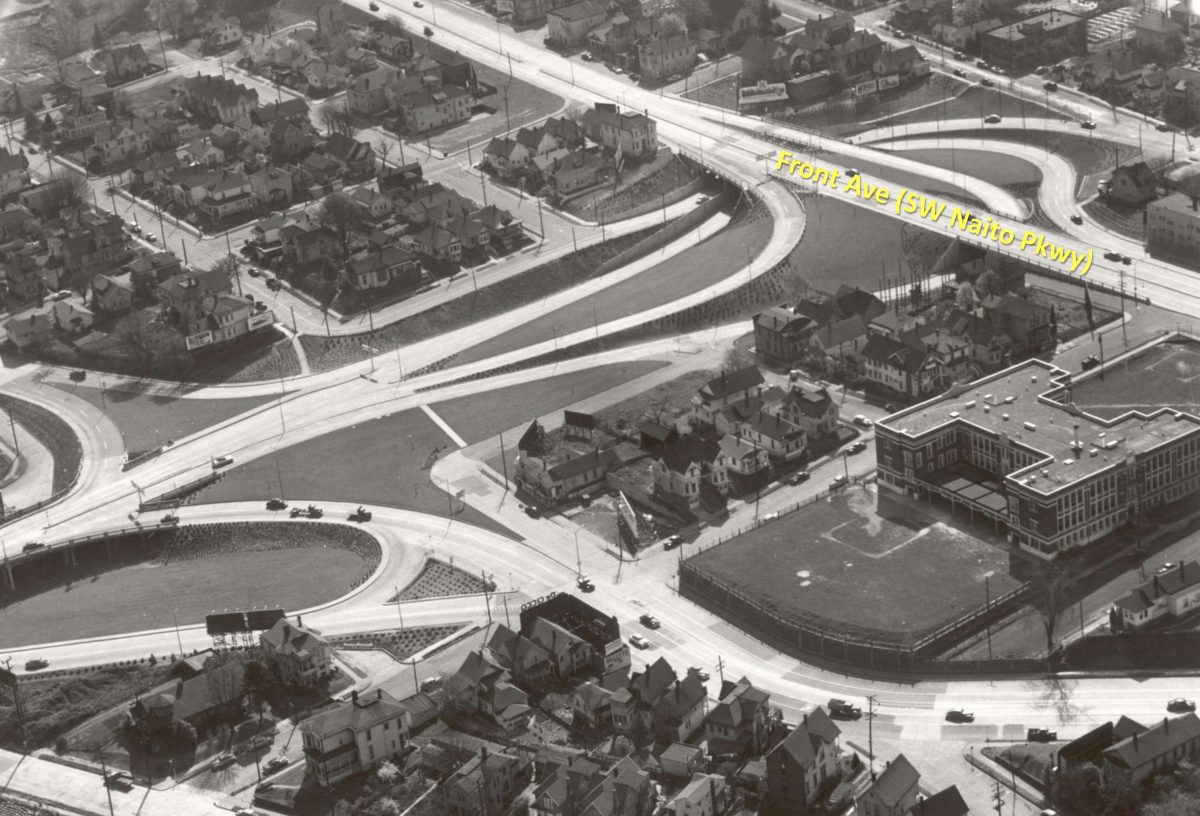

BPS project manager Kevin Bond set the context with the most detailed and honest presentation of local urban planning history I’ve ever seen at a public meeting (and I’ve seen a lot of them!). It’s common to hear land acknowledgements to honor native tribes in Portland, but Bond went above and beyond. Displaying a slide that showed the area as it looked in 1879, Bond explained, “Going all the way back to the first harmful impacts from European settlers on Native Americans, there have been impacts from past auto infrastructure projects, land use regulations, urban renewal and real estate practices that shaped the growth of South Portland for generations.” He explained that people of the Chinook and Cowlitz tribes suffered from the first wave of displacement (both physically and by disease) that came with the white settlers.

Then came the highways.

Advertisement

(Old photos of the area provided by BPS.)

The Ross Island Bridge (U.S. Highway 26) was built in 1926 and its ramps and connections to Naito Parkway (State Highway 99W) resulted in the loss of many homes and businesses. This “highway-style road design” PBOT project manager Patrick Sweeney explained, destroyed the existing street grid and adjacent communities which were populated by 40% foreign-born residents in 1940. After the highways went in, more homes and businesses were destroyed in the name of urban renewal. City records show that the South Auditorium Urban Renewal Project displaced over 500 households, and 200 businesses between 1958 and 1974. Redlining, a discriminatory real estate practice that prevented immigrants and people of color (especially Black people) from getting home loans, also played a big role in this area. Bond didn’t just mention the term in passing, he quoted from real estate lending documents that called for a desire to keep out, “detrimental influences, such as presence of subversive foreign populations” and that, “The concentration of Orientals and other foreign born populations is confined to the northern half of the area.”

“This is restoring a neighborhood connectivity that hasn’t been in place for decades and decades and decades.”

— Patrick Sweeney, PBOT

The people who remain still suffer from negative impacts of the highways. Bond said it’s time to do things differently.

“When you drive by today you might not even realize there’s a neighborhood there,” he said at Tuesday’s meeting. “The city is committed to ensuring that new plans and new investments redress these past harms and honor the history of South Portland.” That commitment includes an equity analysis being done as part of the project that will identify who benefited and who was harmed by this past, “And how the Ross Island Bridge and Naito improvements can be designed for more equitable outcomes in the future.”

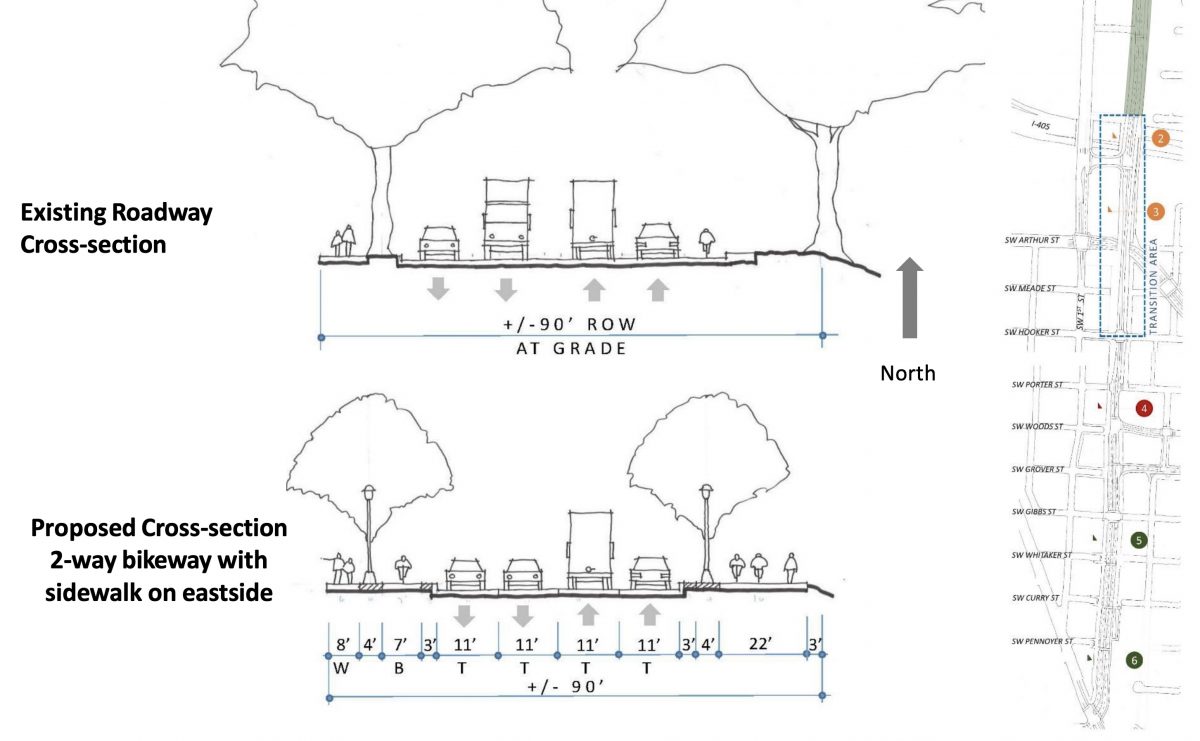

For PBOT and BPS that future means transitioning Naito from an urban highway to a more livable main street with what Sweeney refers to as, “a multimodal street network”.

While PBOT works on street plans, BPS’s role is to pass a package of zoning and street classification changes and create development concepts that will define the future Naito Main Street Corridor. They hope to have a draft plan ready for adoption by Portland City Council in spring of next year.

PBOT sees this as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to reconnect South Portland to the the central city and other southwest neighborhoods. “When you consider all these things working together,” said PBOT project manager Patrick Sweeney, “This is restoring a neighborhood connectivity that hasn’t been in place for decades and decades and decades.”

How will they do it? “The ramps come out and the streets go in,” Sweeney said.

Advertisement

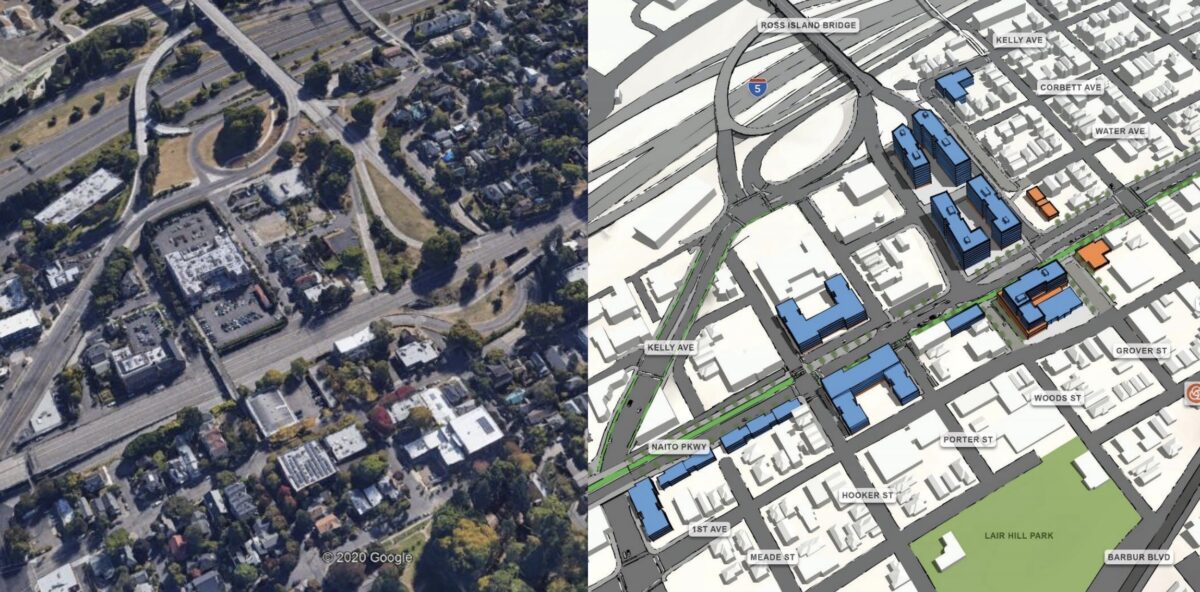

Specifically, PBOT wants to remove the Naito and Kelly Avenue/Highway 43 ramps on the western Ross Island bridgehead. This will give the city three new blocks to redevelop with much-needed housing and a new street grid.

(Before/after concept drawings.)

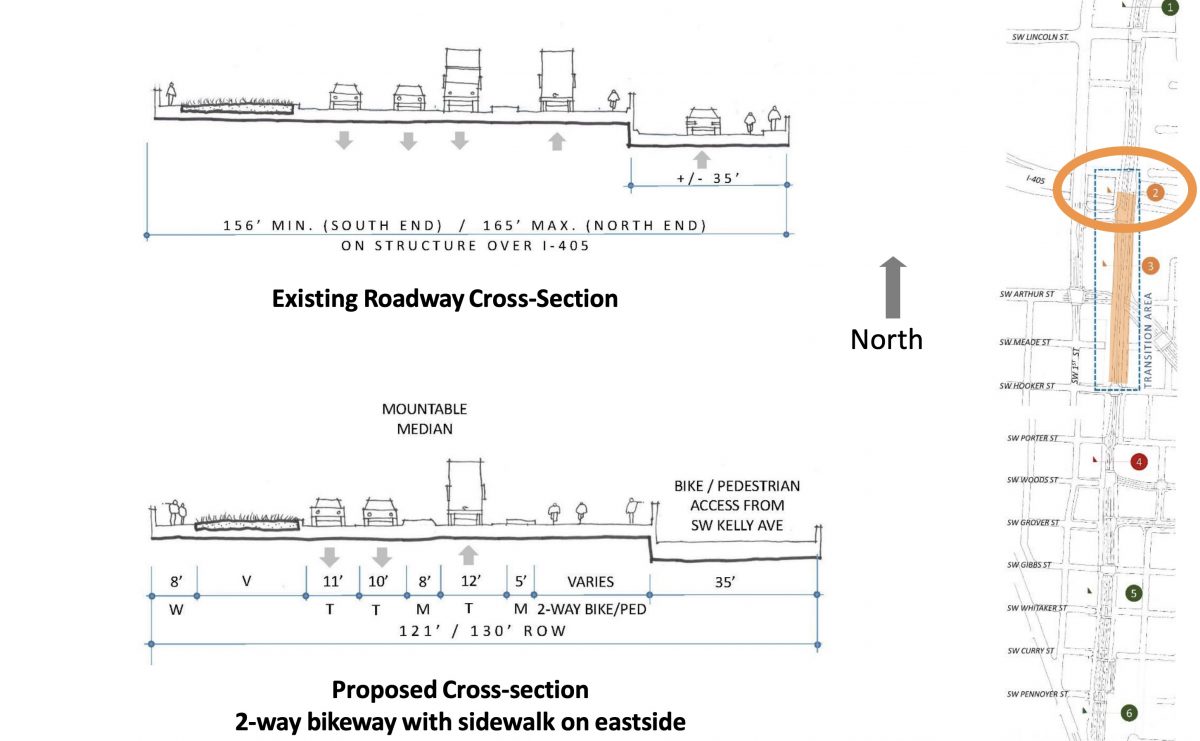

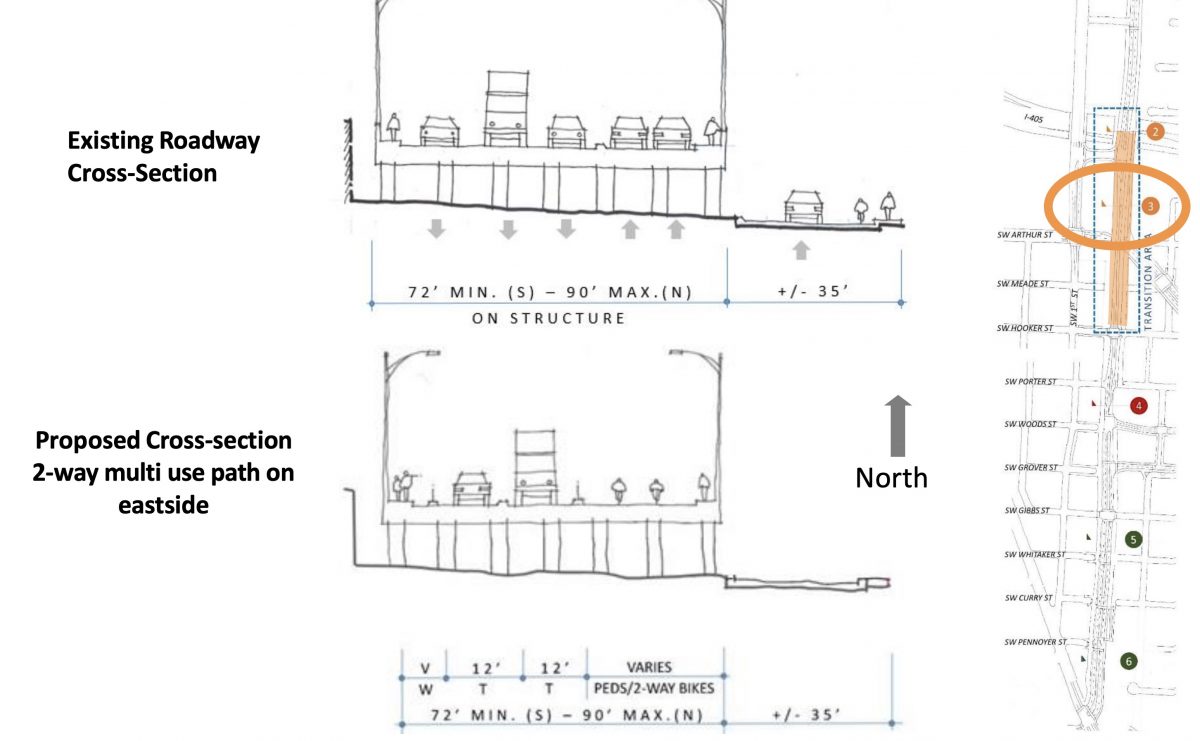

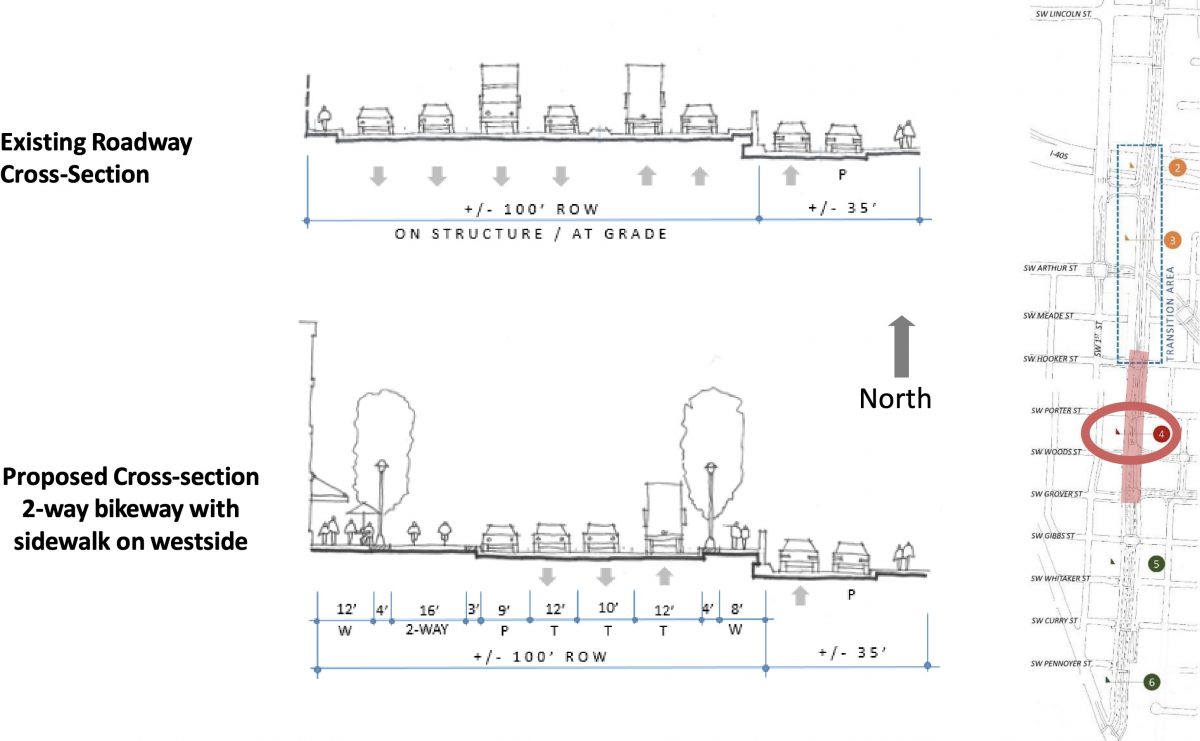

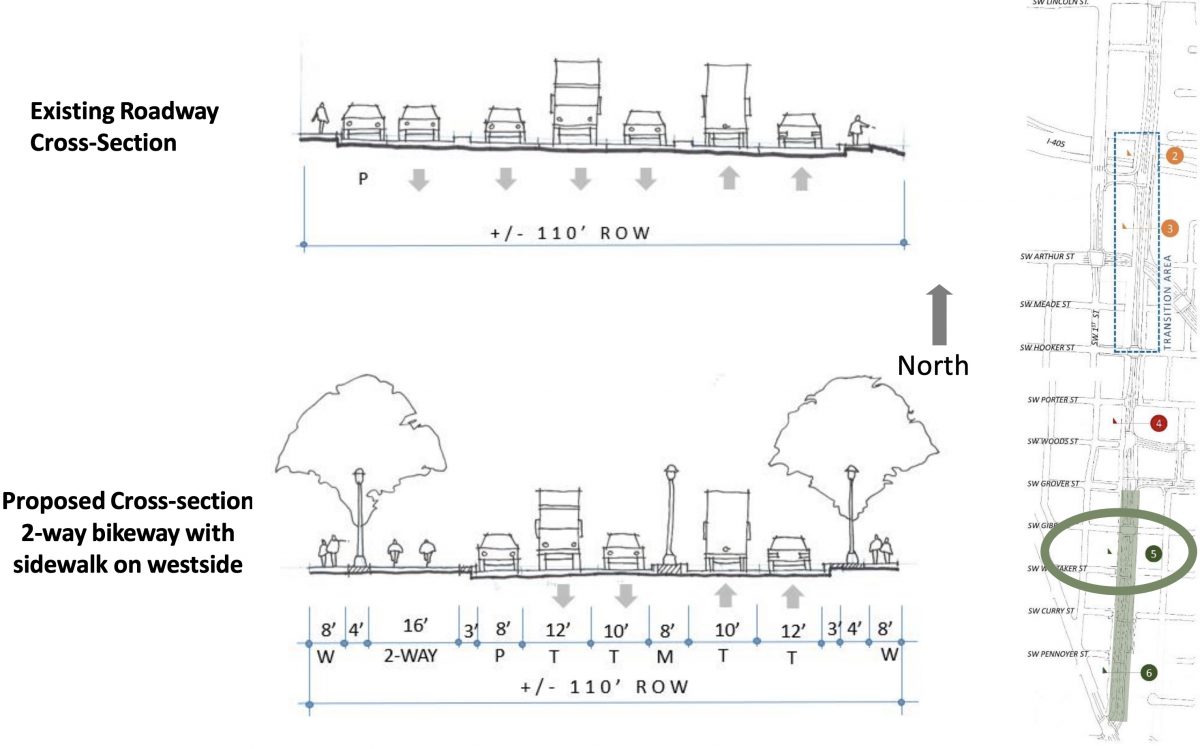

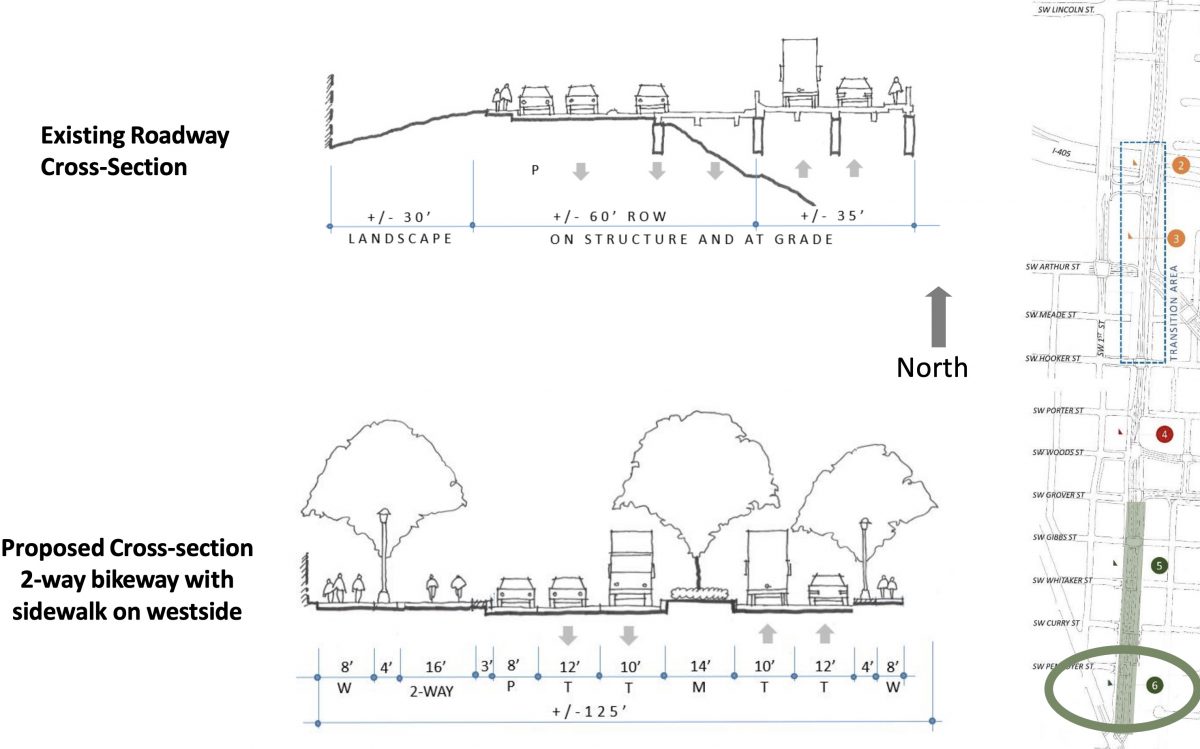

Key to the plans is a major reconfiguration of Naito from state highway to complete street. Traveling from north to south, below are some of the new cross-sections in the works:

Northern end of the project near SW Lincoln;

The “Viaduct zone” between I-405 and south to Hooker St;

The northern end of the project would tie into PBOT’s SW Naito Parkway Improvement Project which broke ground in July. And the southern end of this project will tie into TriMet’s Southwest Corridor project (if it ever gets built) at Barbur Boulevard.

Whether or not this project happens sooner or later all depends on the fate of Metro’s transportation measure 26-218 that’s currently on the ballot. It’s slated to receive $74.7 million of the $240 million set aside in the measure for a slate of Central City projects. If the measure passes construction could start as soon as 2024. If it doesn’t construction won’t start until 2028 (that is, if it earns grant funding).

To learn more about this project, see PBOT’s website or watch a video of Tuesday’s meeting.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.