“That first and final mile is just huge. And I can really see Biketown being a key part of this, especially with e-bikes.”

— Susan Bladholm, Frog Ferry

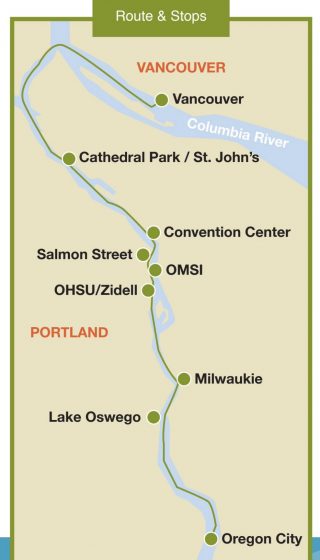

A public passenger ferry system that would serve 9 stops between Vancouver and Oregon City on the Willamette River would cost about $40 million to launch and would need about $7 million a year to operate. Those are just two takeaways from the Operational Feasibility Study and Finance Plan released by Frog Ferry this morning (PDF).

Frog Ferry, a nonprofit that first floated the idea of a carfree ferry system in 2017, has made major progress toward their goals since we first covered them two years ago.

At the online press conference Tuesday morning, Frog Ferry Founder and President Susan Bladholm said ferries offer, “An amazing opportunity to expand our transportation network at a fraction of the cost of other modes.” Bladholm then shared a new promotional video where a narrator said, “Imagine getting to work faster, while feeling your heart beat slower.” “Welcome to Frog Ferry, a walk-on, walk-off boat that will whisk people up and down the Portland area with a vision to go even further… The time for Frog Ferry is now. The river is our transportation future.”

Bladholm and her supporters have reason to be excited. Since 2017 they’ve put together an impressive list of backers and board members, secured a $200,000 planning grant from the Oregon Department of Transportation (which included $40,000 from the Portland Bureau of Transportation), claim to have raised $750,000 from donors and added 1,600 people to the Friends of Frog Ferry support group, have used the equivalent of over $5 million in pro bono management and marketing work and have published three reports (best practices, demand modeling and now operational finances and feasibility).

Here are the main takeaways from their latest report:

Advertisement

- Recommendation of seven vessels (with different sizes south and north of OMSI based on river environments and wake zone regulations).

- Average 3,000 passengers a day and 800,000 per year

- Capital Costs ($40 million): Planning, engineering, vessel and equipment acquisition, and regulatory requirements

- Operating Costs ($6.8 million): Labor, fuel, insurance, maintenance, technology, communications and training

- Annual subsidy: $2.5 million (ticket revenue covers 45% of costs)

- Cost per passenger: $8.50

- Average passenger ticket price: $5 per passenger | $3 for honored passenger

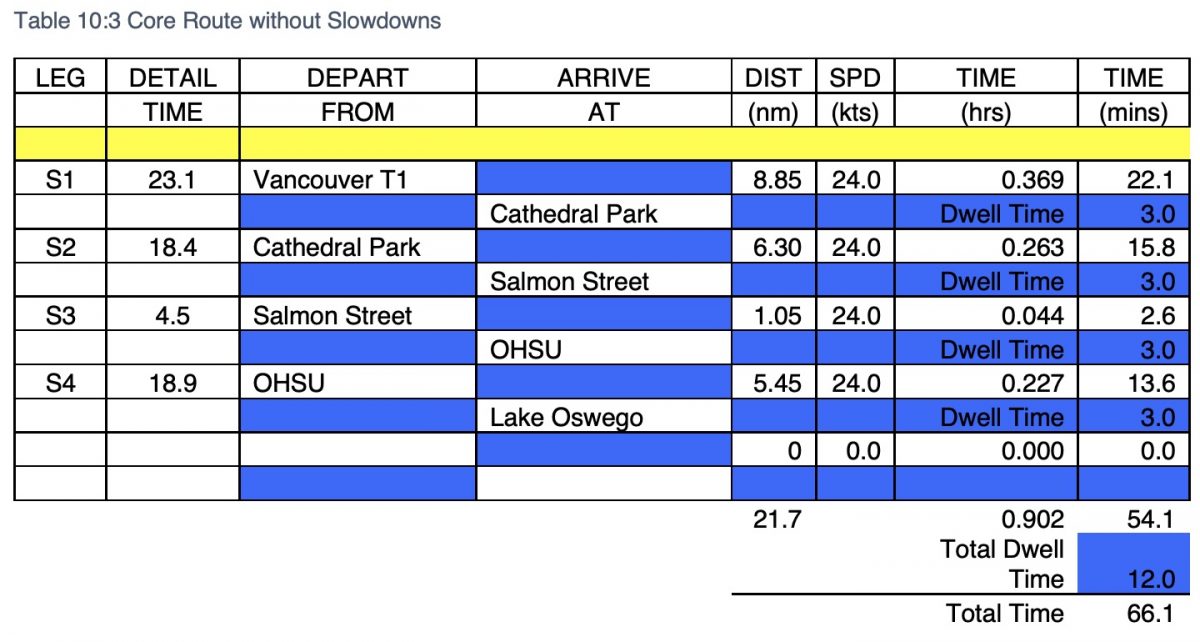

The route would be split into two sections, a lower river route (north of downtown) and upper river route (south of downtown). Five terminals would be included in the “core route”: Vancouver (Terminal 1), Cathedral Park, Salmon Street, OHSU, and Lake Oswego. Time estimates for a trip between Vancouver and Salmon Street Fountain would be about 44 minutes on an express route and 55 minutes with a stop at Cathedral Park. Headways between ferries would be 30 minutes max.

The boats would vary between 90 and 65 feet long and would have room for 100 and 70 passengers respectively. In an interview last week Bladholm told me the smaller vessels would have space to park 12 bikes and the larger ones would be able to fit about 15 bikes.

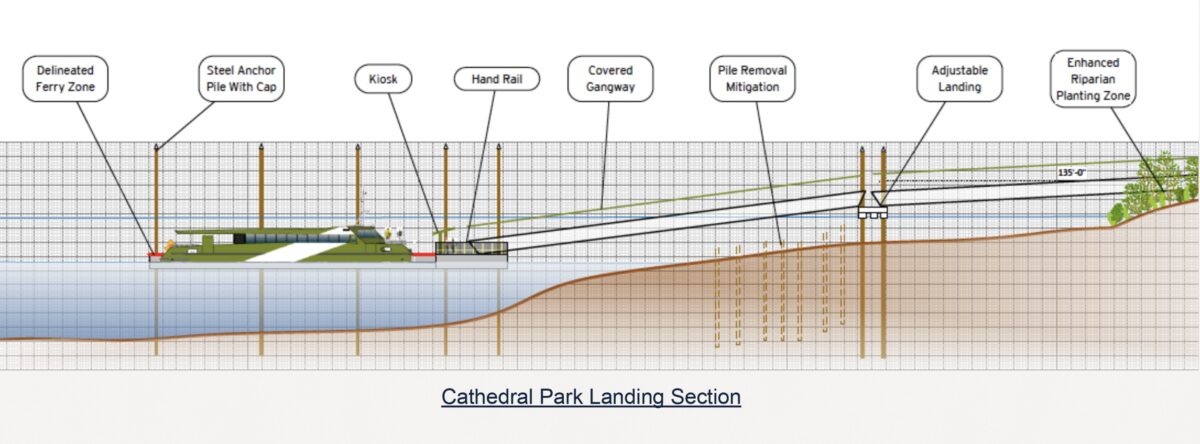

The estimated number of people who will ride bikes to the docks is unknown at this point. Bladholm hopes to complete a more detailed modeling study next year. One thing we do know is that many riverfront locations are not easy to get to by bike (or foot for that matter). Cathedral Park in St. Johns for instance is expected to be a key Frog Ferry station. Unfortunately the riverfront is down a steep hill and the dock would require people to cross heavy railroad tracks. “That first and final mile is just huge,” Bladholm said when I asked her about this. “And I can really see Biketown [bike share] being a key part of this, especially with e-bikes.”

The report acknowledges the important role of bicycle access, bike parking, bike share, and walking. People on foot should be able to reach ferry terminals “uninhibited” and bicycle access at both ends of a trip, “will be of critical importance” the report states. Since the boats won’t be able to fit everyone’s bikes, “Secure bike parking in close proximity to the terminal is essential,” it adds.

Commuters were expected to be the top user segment of the new ferries. Even with major commute behavior changes brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, Bladholm believes there’s a need for ferries. Using the Cathedral Park example, she said her contacts at OHSU tallied about 500 employees a day coming from St. Johns to the south Waterfront campus and Marquam Hill. Today that number is around 300. “That count is great for us,” Bladholm said, while explaining how a typical bus commute would be over an hour and a ferry ride would be just 22 minutes.

Addressing the Covid impact in a recent newsletter to supporters, Bladholm said, “Our public agencies are recalibrating planning strategies and looking at low-cost, high-value ways to build our economic vitality while improving our environmental footprint. This is an opportunity to revisit our values in a more meaningful way, rather than continuing with the status quo of transit planning based on what has been done in the past.”

Beyond commuters, Frog Ferry’s three other target markets are: first responders and “citizens in distress” during an emergency, locals running errands or meeting friends, and tourists.

Advertisement

Bladholm said she’s comfortable being in the role of pushing for something new that gets dismissed by some people. Back in 1987 when she was 22 and fresh out of college, Bladholm took a job working with Oregon’s first-ever state tourism director. Her first assignment was to look into a new thing called Cycle Oregon that her boss had read about in the newspaper. Bladholm dove head-first into the job and traveled to Iowa to learn about large group rides first-hand at the legendary RAGBRAI event. When Cycle Oregon launched in 1988 Bladholm was its first ride director and she served in that role for three years.

“Pre Cycle Oregon we had no cycling culture here, let alone no infrastructure,” Bladholm shared with me last week. “So this is so reminiscent of it, it’s just that I’ve got the benefit of being 32 years older.” “We’ve been backed into that corner so many times and told, ‘You’ve got to do this, you got to do that. Oh, here are three more things you’ve got to do’. Well we’ve done them now,” she added, confidently.

Bladholm will need this confidence to take the major steps that remain before any boats get on the water.

Frog Ferry needs to find a public agency sponsor to help them get in line for major federal funding. So far no one has stepped up. An operational model they’re looking to is something similar to Portland Streetcar Inc., whose director Dan Bower sits on the Frog Ferry board (he also used to be head of active transportation at Portland Bureau of Transportation). The other to-do item atop Bladholm’s list is to plan and fund a pilot project that would begin in 2022.

If all goes according to plan Frog Ferry will be in region-wide operation by summer 2024.

(Below is the Frog Ferry promo video released today.)

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.