One of the best things about bikes is how they lead to so much discovery. In urban areas their relatively slow pace and open-air design helps connect people to their surroundings in a much more intimate way than cars do. And when riding on trails, bikes can take you to awe-inspiring places where rocks, water, trees and dirt create mother nature’s murals.

“A bike saddle is the perfect vantage point for viewing landscapes and the geology that forms them because you can’t escape from interacting with them, and the landscapes drive your experience on the bike.”

Just like urban mural paintings have meaning beyond the surface of their colors and images, earth’s natural features tell a much deeper story than meets the eye. Unfortunately most of us don’t have a riding buddy with a Ph.D. in geology to satisfy our innate curiosity about the places we ride and explain why those rocks and dirt look like they do. That’s where Portland resident Lalo Guerrero comes in.

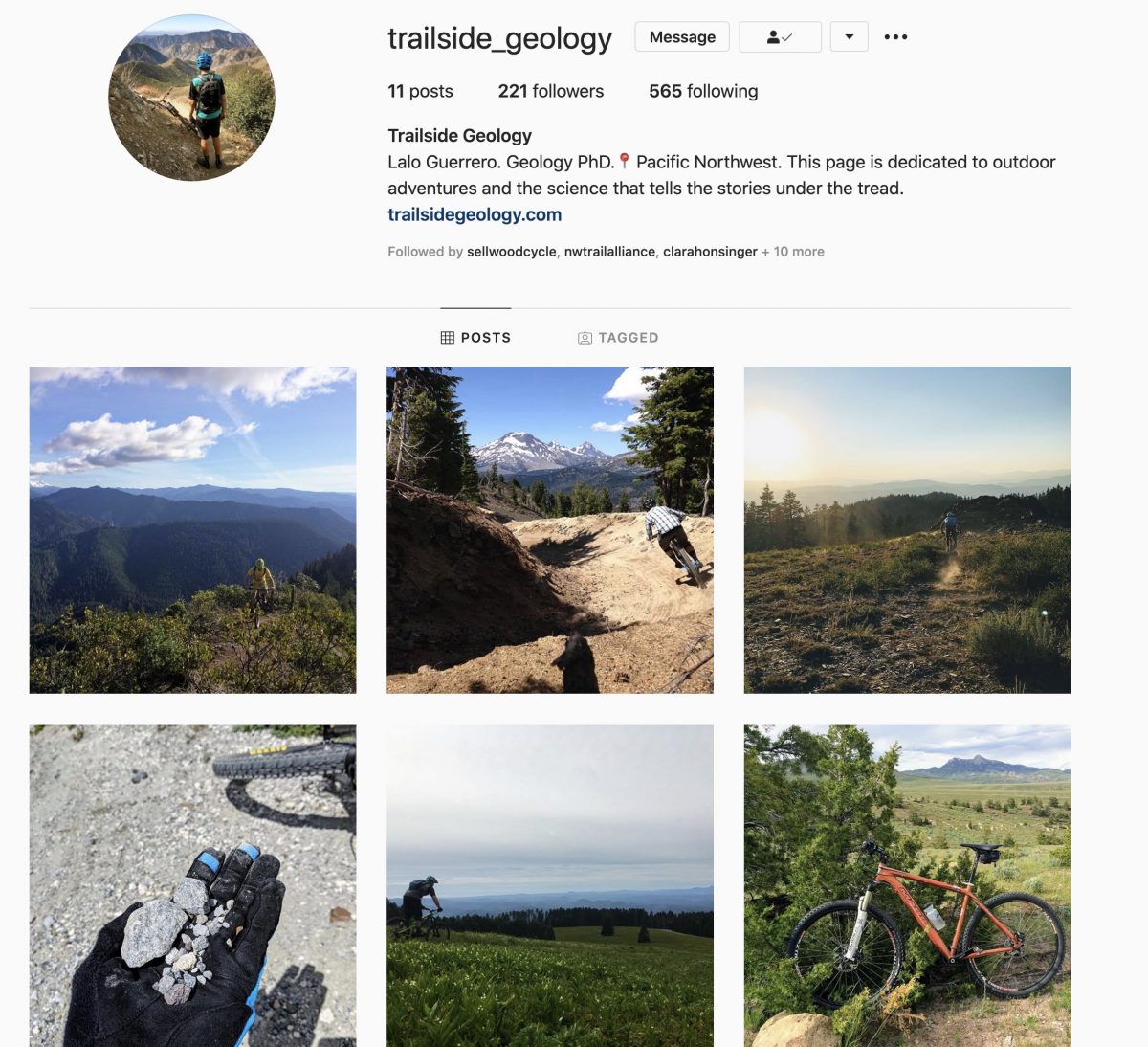

Guerrero has found an eager following for his “Trailside Geology” lessons based on natural features of trails he comes across while riding his mountain bike on popular trails throughout Oregon.

“This spot is brought to you by an igneous intrusion of Diorite, which means that these rocks were part of a volcano’s plumbing system,” Guerrero shared on his Instagram account during a ride on a popular trail at Sandy Ridge Trail System. “When the magma began to cool underground, the mineral ingredients have time to develop their crystal structure, which in turn makes them more resistant to weathering and erosion, leaving behind these proud boulders where we challenge ourselves.”

Born in Mexico, Guerrero moved to Portland in 2017 after he earned a Ph.D. in Geology from Oregon State University. He’s currently on the Earth Sciences faculty at Portland Community College’s Cascade Campus and lives in outer northeast Portland.

I asked Guerrero to share a bit more about himself and his love of rocks…

What came first? Interest in geology or MTB?

“It’s hard to say. The summer I learned to ride a BMX bike in the early 90’s was also the summer I first visited Lassen Volcanic National Park for the first time and both of those events changed my world and set me on the path that I’m now on. It took me a couple of years after finishing my undergraduate degree in Geology to get a new bike. I started riding and road racing in Northern California but ended up buying a mountain bike in 2009 because we adopted a german shepherd who needed A LOT of exercise. That’s when I fell in love with mountain biking. Racing cross-country when we moved to Oregon led me to start exploring a lot of the state, and I found myself constantly geeking out with my buddies about the rocks and the landscapes we were seeing, so I thought that it’d be cool to combine two of my biggest passions!”

Advertisement

Why do geology and mountain biking go together?

“I feel that a bike saddle is the perfect vantage point for viewing landscapes and the geology that forms them because you can’t escape from interacting with them, and the landscapes drive your experience on the bike. I still love riding on the road, however, I love MTB because you don’t run the risk of getting hit by a car if you stop to check out a rock outcrop somewhere along a trail.

Geology and geological processes are what make landscapes unique, so the features and the trail designs that you experience on the bike are limited by geology. This includes everything from the slope, trail tread, trailside exposure, technical features, switchbacks, etc.

I think that folks who ride MTB are typically painted with the same brush of being ‘adrenaline junkies’ who just ‘like to go fast’, and my aim with Trailside Geology is to highlight the fact that recreating on bikes can coexist with learning and caring about the places that we ride, which is more reflective of my experiences within the community.”

Have you ridden MTB in other regions? How does the Pacific Northwest compare from a geology perspective?

“The diversity of the trails that we have access to in Oregon is in large part thanks to the Cascadia subduction zone, which forms the Cascade volcanoes due to melting associated with downgoing Juan de Fuca plate. Subduction and melting of the crust has produced a huge variety of rock types that provide tremendous diversity for material and their associated landscapes. Subduction also led to the development of the Oregon Coast Range, which has uplifted marine sedimentary deposits like sandstones, mudstones, and siltstones, each of which weathers differently and provides different drainage qualities, which ends up determining whether you’re riding through well drained sandy soils or get stuck in a bog during winter.

It’s going to sound like a cop-out, but my favorite trail is always the last one I rode on. I’ve had wonderful experiences riding in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Arizona, California, and Washington. Geology is unique in each one of those spots, and I’ve had memorable rides in each state because of the geology and the efforts of the trail building communities in those states.”

Advertisement

Any local geological facts/wonders that might surprise someone who’s not a geology expert?

“There are a few that come to mind. The Portland Hills are covered by fine-grained silt, which is silt which was deposited during the last ice age either as wind-transported material or sediment carried by the Missoula floods. The material weathers very easily, and contributes to the occurrence of all of the landslides and road closures that folks who live and ride in the area might have experienced.

Most everyone who’s ridden on Mt. Tabor might have heard that it is an extinct volcano, which is true. What might not be common knowledge is the fact that Mt. Tabor, Rocky Butte, Powell Butte, and most of the hills in East Portland, all the way to Larch Mountain are all related to each other. They are part of the Boring Volcanic Field which was actively erupting between 2.5 million years and 50,000 years ago.”

How much does geology play a role when you consider what ride to do? Do you ever think, “Nah, I don’t want to ride there, the geology is too boring.”?

“The really nice thing about planning a trail ride around the geology is that most trail systems tend to be confined to specific and unique landscapes that are formed by the same geologic processes. There are a few exceptions (like McKenzie River Trail), but by-and-large on any given day, you’ll see different expressions of the same geologic materials and processes. I love long trailside descents like the MRT because you get to experience a wide range of geologic processes.

To get at your second question, I’d go back to something I said earlier – it’s really tough to have a bad trail ride when you’re learning about the place you’re riding, it all becomes about discovery and seeing areas in a new light. I’d say that my only really complaint when it comes to riding in a new area would be if the trail system just ignores the landscape, and fortunately, trail builders in Oregon do a really good job of respecting the natural landscape and building some amazing trails.”

If these pandemic group-riding restrictions ever ease, Guerrero wants to offer guided road, gravel, and trail rides. He also wanted me to mention one of his inspirations, Ian Madin from the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. Madin is Cycle Oregon’s official geology expert and his nightly lectures are a highlight of the ride.

And yes, Guerrero takes requests! If you’re curious about something you’ve seen while riding, email him at info@trailsidegeology(dot)com. Or connect with him via Instagram or Facebook.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.