(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

This is crossposted from the Sightline Institute. Michael Andersen is a former BikePortland news editor.

The proposal going before Portland City Council at 2 pm today would be the city’s most important biking infrastructure investment in 20 years, and its most important bus infrastructure investment in 40.

Just as importantly, it’d also make our streets work better, permanently.

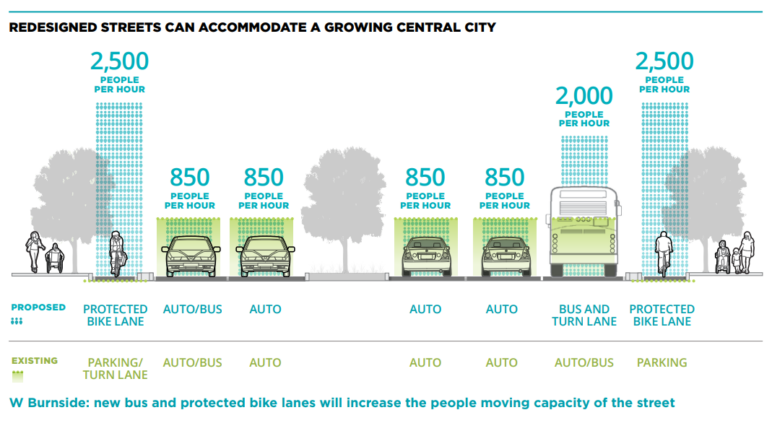

The Central City in Motion plan avoids the false promise of bigger roads: 39 percent of the central city is already dedicated to street space, it notes. So, as Jonathan reported last month, it’s planning to dedicate an additional 1 percent of those central streets to bike lanes and another 1 percent to bus lanes.

That little shift in urban space, which would take the form of 18 street projects over the next 10 years, would boost the people-moving capacity of the affected streets by an average of 60 percent.

That’s based on calculations from the National Association of City Transportation Officials. Need more proof? Ask TriMet, who just revealed that relatively tiny lane tweaks led to a significant decrease in delays on several lines.

Price tag: $72 million, or about the cost of a single mile of urban freeway.

“Just like a road network or a computer network, low-stress bikeways have little value to anyone until they’re connected to other low-stress bikeways.”

It’s worth noting that boosting the potential capacity of a street isn’t the same as getting people to use that potential by riding a bike or getting on a bus. And one potential risk of Portland’s current plan is that a big part of it—a connected lattice of low-stress bike lanes on Burnside, SW Broadway, SW 4th, NE/SE 7th, SW Madison, NW 14th, NW Everett, SW Salmon, SW Taylor, SE Hawthorne, NE Multnomah, NE Lloyd, Naito Parkway, NE Broadway, and NE Weidler —might not pay off much until the entire network is finished.

Just like a road network or a computer network, low-stress bikeways have little value to anyone until they’re connected to other low-stress bikeways.

Some cities—Vancouver, BC; Calgary, Alberta; Sevilla, Spain—have recently shown the power of installing a simple protected bike lane network all at once, with relatively cheap and adjustable materials, so transportation habits can shift quickly and everyone—voters, nearby businesses, politicians themselves—can see the payoff. It’s not clear whether or not Portland is planning to learn from that example as it builds its own network.

That said, the only way a city can truly fight traffic is to better use the street space that already exists. If Portland moves this plan forward, it’ll become the latest city to show the rest of the world how to fight congestion right, and allow more people to enjoy the blessings of the city.

— Michael Andersen, Sightline Institute

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.