(Photo: Bejan)

The Portland metro area was one of the fastest job creators in the country in 2015, but a familiar neighbor has been neck and neck on that measure: Seattle.

The city to Portland’s north has ridden the success of Amazon and Microsoft, among others, to the country’s third-highest average wages. (Portland ranks 10th.) But all the money has come at a cost: Seattle rents are 20 percent higher than Portland’s, on average.

That isn’t likely to change any time soon. The most walkable and bikeable parts of Seattle remain even further out of reach for poor people than the most walkable and bikeable parts of Portland do today.

But Seattle’s recent real estate news suggests one way to at least stop rents from going even higher.

The trick, according to the Puget Sound Business Journal: give richer people somewhere to move that is not currently occupied by a less rich person.

This is from a Nov. 23 PSBJ article (written, naturally, from the perspective of a landlord or developer who would be horrified by falling rents):

It’s not demand that has Seattle apartment landlords worried. It’s supply. …

There are 22,000 units projected to open this year and next. Combine that with the 7,400 units developers opened last year – the highest level of production seen locally since 1991 – and it’s easy to see why landlords are concerned.

“It’s interesting right now because supply, I think, is definitely having more of an impact and a drag on the market right now more than anything else,” said Pettit during a Bisnow event.

There are some reports that occupancy rates in some newer buildings that have been open for a couple years are as high as 97 percent. Basically, the buildings are almost completely filled. But that’s not what Pillar Properties is finding when checking in with competing landlords. Their teams are telling Pillar’s that occupancy is actually only around 92 to 94 percent.

This means rents won’t increase at the rate that some sources say they will, Pettit said.

The issue of slowing rents is most acute in Seattle neighborhoods that are experiencing an unprecedented amount of development, according to Dupre + Scott Apartment Advisors.

And here’s a follow-up article from last week, drawing on more recent data:

The big warning sign for landlords is what the report says is “price resistance” in the most expensive submarkets: the downtowns of Bellevue and Seattle, including Belltown and South Lake Union, and Sammamish/Issaquah. After increasing during the first three quarters, rents dropped this quarter in all but South Lake Union, with the average decline hitting $59 a month. Further, when all of these submarkets are considered, the average vacancy rate increase was nearly a full percentage point.

Meanwhile, across all markets, more landlords are offering tenants sweeter incentives, such as free rent. The average value of incentives is $15 a month this quarter, which is nearly double what it was last quarter, when 16 percent of landlords were offering incentives. Now 20 percent are.

Advertisement

Portland is adding homes too, but rents have been anything but stable

For Portlanders, this news from Seattle raises a question: with all the building we’ve seen 2014 and 2015, could the same thing be happening here?

Not yet.

“Portland’s multifamily market continues on a tear without any signs of slowing down,” Portland real estate analyst Norris, Beggs and Simpson wrote in their third-quarter report on local multifamily rents. “Though the rate of construction has subsided, capital continues to flood the market.”

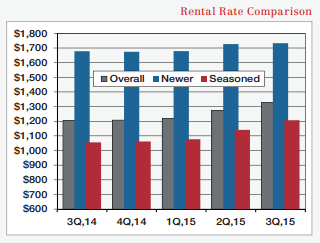

Here’s a chart from NB&S showing how rents have edged up only slightly for new units, while the rents for older units (euphemism: “seasoned”) have leaped more than $150.

The $100 per month rise in the price of the average Portland rental unit has been devastating for lower-income Portlanders. Remember 2014, when the Portland Business Alliance was up in arms about an “incendiary” citywide income tax for transportation that would have topped out at $900 per year for people making more than $333,000?

In the year that followed, the average citywide rent rose $1,200 a year.

Did you notice the Portland Business Alliance (which is the regional chamber of commerce) hitting the panic button about the effect that will have on the business environment?

Yeah, we didn’t, either.

Seattle has been adding people faster than Portland, but adding new homes faster still

If new building seems to be helping Seattle slow its rent increases, why isn’t the same thing happening in Portland?

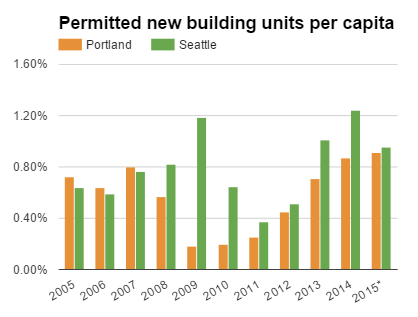

Though it’s a little hard to compare one city’s building rate to another, one way to start is to use Census figures to calculate the number of new homes permitted per resident. Here’s what that looks like for Seattle and Portland over the last 10 years:

Over the 11-year period, Seattle has added 66 percent more new units per capita than Portland. That’s mostly because of the huge surge it saw in 2009 and 2010, when development in Portland slowed to about 1,000 units per year but 1,000 new Portlanders were still arriving every month.

A big reason Seattle has built more, no doubt, is that housing prices there have been higher. In a housing market that’s overwhelmingly funded by the private sector, the best way to create more housing is for the new units to be worth a lot of money. Unless taxpayers are chipping in too, that’s the only way it works, unfortunately.

So this isn’t a sign, sadly, that the current U.S. housing system is ever capable of returning the rent in a growing metro area to the level you might see in a metro area that isn’t growing. (The years of very low Portland rents, from 2005 to 2007 or so, happened mostly because Multnomah County was going through its first population decline in decades, caused by a severe, localized unemployment problem in the early 2000s.)

But this story from Seattle is a sign of the role new building can play in the housing market. Unless there’s an economic crash, building can’t make things better for poorer renters. But it can sometimes stop things from getting worse.

Most growing U.S. cities solve this problem by building their new homes at their outskirts. In the last 25 years, Portland has avoided this fate. Assuming we continue to do that, one of two things is going to happen:

- Housing prices in Portland’s bikeable core are going to keep climbing and climbing, which will change what sort of people live there even more than rising rents already have, or

- The buildings in that core are going to have to change even faster than they have been.

Happy new year, Portland. Pick your poison.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here.