(Photo: J.Maus/BikePortland)

Sometime in the 1920s, the American auto industry worked very hard and very consciously to achieve a great victory: they successfully associated their product with freedom.

A machine that had been developed to power farm implements and long-distance travel became a way for the wealthy, and gradually for the less wealthy, to zoom and roar right through the middle of cities.

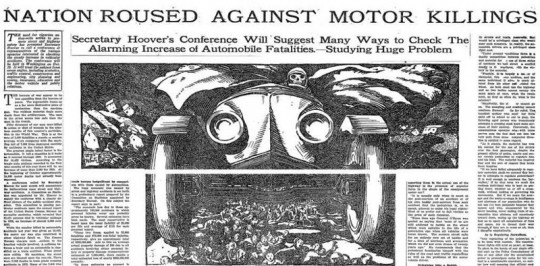

As documented by history professor Peter Norton’s 2008 book Fighting Traffic (and many links over the years in BikePortland’s Monday Roundup), many Americans — maybe most of them — didn’t see this as a blow in favor of freedom; just the opposite. They saw it as a takeover of city streets. Even in a world where many more people died of disease and violence than they do today, the public was shocked by the notion that a person’s freedom to zoom down a street could be more important than a child’s freedom to play in it.

“Children must play,” St. Louis resident C.C. White warned in a letter to the St. Louis Star in 1918. Five years later, a cartoon in that newspaper depicted a car as “The Modern Moloch,” a reference to an Ammonite god who supposedly required the sacrifice of children.

Here in Portland, the mayor, The Oregonian and the police department eventually teamed up to lead a nationally recognized campaign called “Let’s Quit Killing” that treated lethal driving as a private choice but a public problem. Similar movements had already been active in cities across the country.

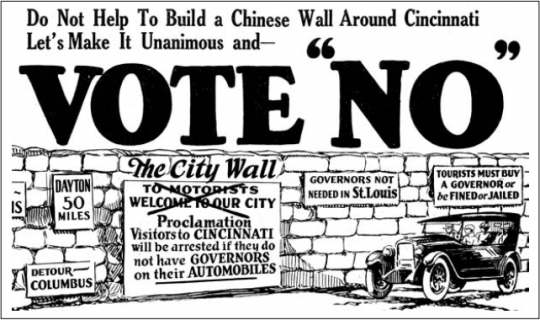

In Cincinnati in 1923, the American movement against the automotive takeover of cities reached its high-water mark: 10 percent of the city’s population signed a ballot initiative that would have required “speed governors” in every car, devices that mechanically limited traffic speeds to a nonlethal 25 mph within city limits.

The auto industry, rightly realizing that without their big speed advantage cars would never be able to compete with streetcars and bicycles as popular ways to get around a city, poured money into lobbying the public for a “no” vote, referring over and over again to the idea that the law would build a “Chinese wall” around Cincinnati. By the time the campaign was over, fewer people voted for the law than had signed the petition.

It’s enough to make somebody wonder about the country that might have been.

Can you imagine what US cities would be like today if safety advocates of 1920s had successfully capped urban auto speeds to 25 mph?

— Michael Andersen (@andersem) June 16, 2015

In the years that followed, advocates of “motordom,” as they referred to themselves, pulled off their most famous trick: they used a derogatory American term for a country bumpkin, a “jay,” to coin a new word, “jaywalking.”

People using the street casually weren’t exercising freedom, the word implied. They were betraying ignorance and unsophistication. They didn’t belong in U.S. cities; cars did.

All of which hopefully explains why I was so intrigued, a few weeks ago, to notice this tweet:

Crossing the street is putting your life at risk at rush hour. Slow down, jaydrivers! https://t.co/jDcAmbsbOm

— Mark (@markecarter) June 17, 2015

And then this one:

#Jaydriver didn't "see" a TriMet bus? No ticket…Why not you ask? Nothing illegal about #jaydriving apparently. https://t.co/CFE6GzBCRy

— Mitchell Austin (@msaplanner) June 11, 2015

And also this:

Just witnessed two people #jaydriving on Clinton almost kill a person biking and walking. Help, @NovickOR ! We need a #SaferClinton!

— Bike Loud PDX (@bikeloudpdx) February 11, 2015

Have you had the prickling sense, lately, that the United States is in a new moment? That the Vision Zero movement and those like it are reviving some of the sense of outrage about the lost freedom of urban movement that almost no one still alive remembers?

Advertisement

Here’s when I felt the prickle: When I noticed that local activist Dan Kaufman had used an image from the Dutch Stop de Kindermoord movement on his Facebook event for May’s traffic safety demonstration on Southeast Powell Boulevard outside Cleveland High School.

The need for the demonstration made me feel sad. But the response to Kaufman’s quick organizing — and the hugely successful two months that Portland livable streets advocates have had since — have made me feel something else: patriotic.

I started to think that even though (unlike in the 1970s Netherlands) almost no one still alive remembers the streets of the 1920s, something big could be happening here in U.S. cities. And that this might be what it looks like.

So when I saw those “jaydriving” tweets, I scrolled through Twitter until I could figure out the people who seemed to be responsible for spreading the term. Then I emailed them to ask why they use the word. Here’s one of them: Mitchell Austin, the Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator for the City of Punta Gorda, Florida:

My first encounter with it was April of 2014 when @PedestrianError … used it in a Tweet. … I just started using it from then on as the situation seemed to cry out for it.

Unfortunately the need to use the term seems to occur all too frequently. The social disconnect that autocentric life causes combined with the distraction of all these little screens seems to have enhanced our propensity to do dumb things behind the wheel. The narcissism of blocking a crosswalk…because 5 feet further in my BMW is more important than your life…or the stress-anger stew car commuters sit in for hours a day…to earn a buck to pay for the car?!?!? It all just seems to be going off the rails for so many people.

I say all this not as some militant anti-car guy. I drive, heck I own two cars in a single driver household. However, there is no reason someone should have to buy, fuel, insure, and maintain a 4,000 lbs hunk of steel, rubber & glass in order to get around & earn a living.

And here’s the pseudonymous woman behind the the account @PedestrianError:

I can’t even remember all the folks who’ve used it. … I don’t think I’d use it on someone who was operating a motor vehicle in a city without breaking any laws or at least standard safety practices (like talking on a hand-held phone in a state that hasn’t yet outlawed it) and it’s certainly possible to jaydrive even in an area where a car might be the most efficient way to get around thanks to limited transit, dispersed land uses and/or lousy biking conditions. I see it more as reckless and/or incompetent driving, which is amplified in an area where no driving is really reasonable. I think use of the term has been waxing and waning for a while, probably slowly but unevenly gaining more traction. … I don’t think I picked it up from someone else but I definitely wouldn’t claim to be the first. It just makes sense.

The birth or rebirth of this little word on a social media platform is a small thing. Even the big idea behind the word — that thoughtless driving, not thoughtless walking, is out of place on city streets — isn’t enough to restore the independence Americans lost when we gradually handed city streets over to traffic and began to build our cities around our machines, not fully realizing the costs until it was too late.

But from a gradually spreading grassroots hashtag to a Portland dad worried about his children’s safety to residents mobilizing for a voice on their neighborhood association to one of America’s great cities announcing that despite our country’s choices in the 1920s, we no longer find traffic deaths to be an acceptable price to pay for speeed, the national movement for better streets that’s being built right now is showing signs of a very American attitude. It’s actually the same attitude that advocates of “motordom” had when they gradually wrested control of city streets, supposedly in the name of freedom, 90 years ago.

Independence isn’t something you receive.

Independence is something you declare.