(Photos: M.Andersen and J.Maus/BikePortland)

Do bikes count?

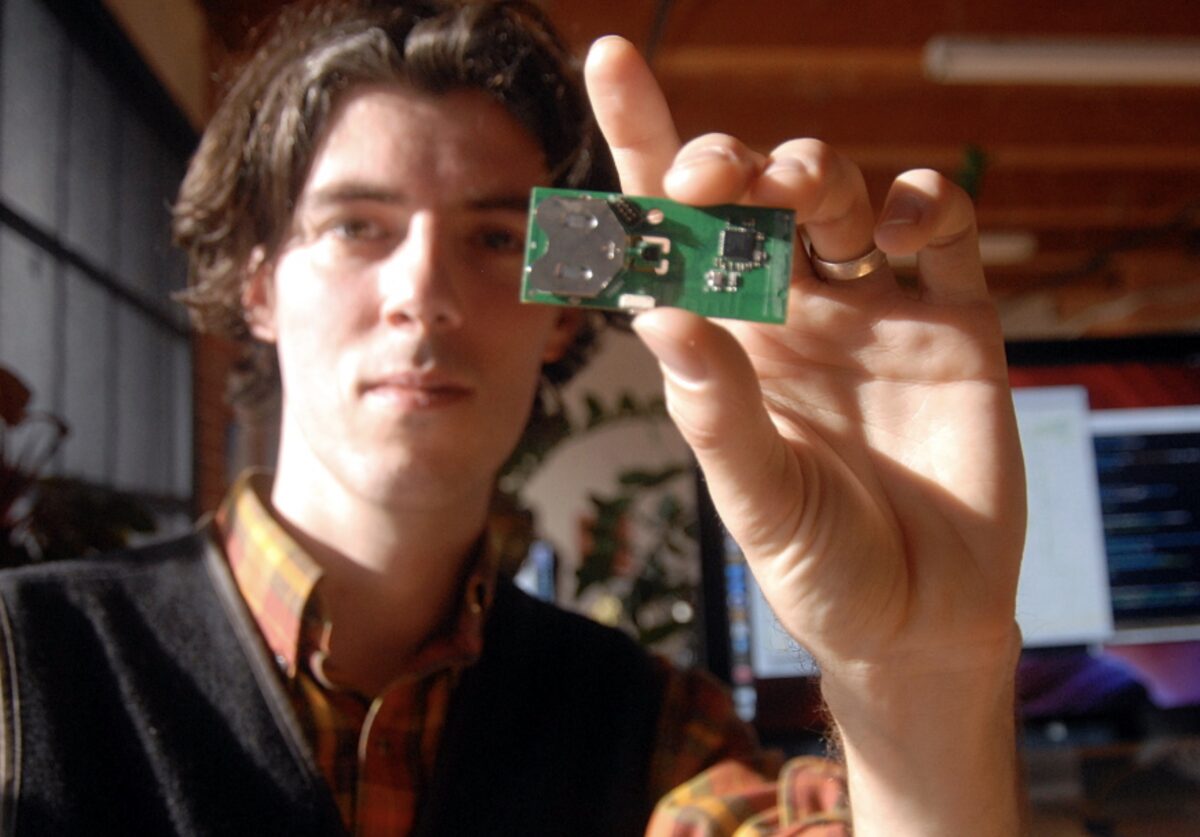

A three-person Portland startup that hit a jackpot with its first mobile app is plowing profits into a new venture: a cheap, tiny device that could reinvent the science of measuring bike traffic — and help see, for the first time, thousands of people that even the bike-friendliest American cities ignore.

Tomorrow, Portland’s city council will consider a proposal to become their first client.

An app-store hit fuels a passion project

When I meet him in his company’s office three floors above Ash Street, William Henderson tells me he doesn’t smile in photos.

“People will think I’m not working,” he says. Then he grins.

Henderson shouldn’t be worried. After graduating from Portland’s Reed College in 2008, he spent two years at Apple before moving to Square, where he worked as lead mobile engineer and then directed the creation of Square Wallet, the ecstatically reviewed but ultimately unsuccessful service that, for a while, let you pay for any Starbucks drink by telling the cashier your name.

Last year, his bootstrapped startup Knock Software created a $4 app that lets you log securely into a Mac by tapping your knuckle twice against your smartphone.

It’s been a hit. So Henderson, a daily bike commuter here in Portland, decided that his next product would try to improve something he cared about: transportation.

“We got lucky and made a product that did pretty well,” he said. “So we have this awesome luxury, which is money coming in the door for a business, and we can work on something we care about. … Of course we want it to eventually be profitable, but the wolf is away from the door for a little bit.”

Clipboard bike counts: Flawed measurements

Portland’s decade-thick database of two-hour bike counts conducted once a year by people holding clipboards at 200 locations is the envy of cities around the world.

But it’s also, in important ways, awful. Because bikes are counted mostly from 4 to 6 p.m., the city count ignores people who don’t work 9 to 5 and barely measures non-work trips, which account for 80 percent of the places we go. Because it’s done by humans, it requires 560 hours of staff time plus hundreds more volunteer hours. And because Portland’s counts usually cover just one day a year, they can very wildly with weather and special events.

The result: even in Portland, our understanding of bike traffic is far weaker than our understanding of car or transit traffic, and therefore harder to make smart investments in.

Does a neighborhood greenway increase or decrease biking on nearby commercial streets? Do certain designs appeal more to midday travelers than to rush-hour travelers? How do seasons or construction zones affect people’s route or mode choices? As rents in central Portland have spiraled out of reach for people like restaurant workers — 3 percent of the national labor force but 14 percent of bike commuters, according to the Census Bureau — have East Portland streets seen spikes in midday and late-night bike trips?

The answer to every question: we don’t know.

Advertisement

Currently existing bike counters, like the one on the Hawthorne Bridge or the detection loops used at some intersections, are more sensitive but far more expensive. A typical bike counter, Henderson said, requires not only the hardware required to detect the bike and a computer to store the information but on-board cellular equipment with its own data plan. They sell for about $5,000, he said.

According to the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s grant proposal, it’s looking to buy 200 of Henderson’s matchbox-sized portable bike counters for $10,000 — $50 apiece.

How Knock’s bike counter works

Here’s the secret behind Knock Software’s dirt-cheap bike counter: It doesn’t connect to the Internet.

Instead, it detects every passer-by — with or without a smartphone — and keeps a count in its simple, tiny onboard computer. Then it waits.

Knock’s tools for detecting bikes aren’t new. A magnetic panel the size of a grain of rice detects the distortion a bike creates in a magnetic field as it passes. An infrared camera measures the heat pattern of a human. The new bike counting device combines those observations and uses a speed calculation to guess whether the passer-by is in a car, on a bike or on foot.

What’s new, Henderson says, is what happens when someone who’s installed a special smartphone app passes within 20 or 30 feet of his device. Every time that happens, the device uses a low-energy Bluetooth signal to pass the information to that person’s smartphone, which then uses its own Internet connection to pass the stockpiled bike counts anonymously into the cloud.

The passer-by with the special app might be a city employee or volunteer. Or it could be someone who’s installed Knock’s related product: a new mobile bike route-planning app called Ride.

Ride, which entered private beta testing last week, is the other half of Henderson’s big plan. He wants it to be the app you install to get turn-by-turn bike directions customized to your personal comfort level.

But that’s in the future. For now, he’s focused on finding a “core group of people who are using it just because they’re advocates.” Using data voluntarily gathered via those advocates, Henderson hopes to gradually build features that will appeal to the public at large — and to finance the whole thing by selling the bike count devices to cities like Portland.

For Portland, a $40,000 experiment

Portland Active Transportation Manager Margi Bradway said Monday that the city’s proposed relationship with Henderson’s company is an experiment. It’d be funded by $5,000 from her discretionary budget and a $35,000 grant from Mayor Charlie Hales’ $1 million-a-year “Innovation Program.”

Bradway said the Knock devices wouldn’t replace Portland’s annual clipboard counts unless they work. But if they do, “it would free up a ton of staff time and spreadsheet time.”

“If the cost goes down, then we can put them in places that we’re not counting as much right now,” Bradway said. “We aspire to have a lot richer bike infrastructure in East Portland. … This is a way for us to glean a lot more data from those areas.”

Eventually, Henderson said, the features that’ll be offered by the Ride app would let the city measure not just the quantity of bike trips but their quality.

“What I would love is if in three years, we were able to develop what I call an ’emotional level of service’ … how an intersection makes you feel,” he said. “You could give hard data to the city that they could use to evaluate their success.”