In the last five weeks, nearly a third of Portland’s neighborhood associations have approved a resolution that calls for Portland to virtually freeze residential development in the central city at its current average density.

The resolution’s supporters, who call themselves United Neighborhoods for Reform, say it’s not actually an anti-density measure but rather a movement to protect historical character and housing affordability by reducing needless demolitions of old houses.

Margaret Davis, a UNR spokeswoman who also serves as a board member for the Beaumont Wilshire Neighborhood Association, said she wants to prevent home demolitions like one she saw recently.

“The new house that rose up was 2.5 times the size and at least 2.5 times the cost,” said Davis, who said she sometimes works as a small-scale infill developer.

UNR developed out of a series of neighborhood association summits this spring, summer and fall.

Another supporter of the proposal, Brandon Spencer-Hartle of historic preservation nonprofit Restore Oregon, said such projects are becoming common in the hot housing market of Portland’s most walkable and bikeable neighborhoods.

“People are buying small houses for $350,000, $400,000,” he said. “They’re scraping the house. They’re building a maximum square footage house. And they’re selling it for $750,000.”

Language blocking density increases is ‘an oversight,’ backers say

(Photo by sciencesque.)

The resolution signed by Davis and 31 of the city’s 95 neighborhood associations calls on the city, in line 2a, to “limit the mass, footprint, setbacks, and height of construction to that of the average of existing homes within a specified distance.”

“The overwhelming feeling is that the urban growth boundary is a good idea. We’re not anti-density.”

— Margaret Davis, Urban Neighborhoods for Reform

If the “specified distance” were more than a couple blocks, of course, the effect of such a rule would be to effectively prevent density increases on anything except empty lots.

In an interview Monday, Spencer-Hartle called that language “an oversight” and said its backers aren’t actually objecting to the new apartment buildings on some of Portland’s commercial corridors.

“They get it that density needs to live somewhere, and I think they get it that density needs to live along our corridors,” Spencer-Hartle said. “I wouldn’t get on board with a 35-foot height limit on all of our corridors.”

Davis agreed, saying she supports low-car life and is glad more Americans have come to favor central-city living.

“The overwhelming feeling is that the urban growth boundary is a good idea,” said Davis. “We’re not anti-density.”

In a blog post last week, Davis referred to Division Street as a “Death Star Trench” and blamed developers of its new four-story apartment buildings for central-city rent hikes.

As we’ve reported, rents in the bike-friendliest areas of Portland have soared since 2005 amid one of the deepest rental housing shortages in the country.

Davis and Spencer-Hartle said UNR is pushing to restrict redevelopment only in parts of Portland dominated by single-family homes. These areas typically begin a block or so away from the city’s commercial corridors.

“We’re not going to have room to add more units to those neighborhoods unless they cease to be neighborhoods,” Spencer-Hartle said.

Advertisement

Opponent: Allow smaller lots, and smaller homes will follow

(Photo: Mark Lakeman)

Critics of UNR’s proposal say it wouldn’t stop the climb of central-city housing prices and might be counterproductive if it makes it harder to divide a big residential lot into smaller ones.

“We have so many properties in Portland that are 5,000-square-foot to 10,000-square-foot minimums,” said Eli Spevak, another small-scale developer who specializes in small residential projects. “These are pretty big lots in wonderful locations. We should be figuring out how to get more people living on these lots so they can support the neighborhoods that they’re in.”

Spevak conceded that he shares the concern of residents like Davis.

“I think it’s a problem that the average house being demo-ed is less than 1,200 square feet and the average home that is being built is twice that,” he said.

But Spevak said a better way to prevent this might be to allow three small or tiny houses to be built on a single lot instead of one house, or to make it easier for houses to be internally remodeled into two units.

“Let’s build things that look and feel like single-family zoning, but the use of it can be more than one group of people.”

— Eli Spevak, Orange Splot

“Let’s build things that look and feel like single-family zoning, but the use of it can be more than one group of people,” Spevak said. “The market for homes in the $200-$250 range is huge. If someone was allowed to build stuff like that at that price point, I think they would be selling them like crazy.”

Spevak said that because land in central Portland has become so expensive — a vacant 7,875-square-foot lot in Montavilla went on sale last week for $412,000, the Portland Chronicle reported — developers tend to finance their land purchases by putting up the largest and most expensive houses possible.

“The thinking is, if you’re going to pay that much money for the lot, you might as well build a big house,” Spevak said.

25 demolitions in Portland enabled 9 percent of metro area’s 2013 apartment supply

As UNR prepares to head to City Hall next week — the city council has invited them to present their proposal on Dec. 17 — one of their core arguments is that reducing demolitions wouldn’t block future density.

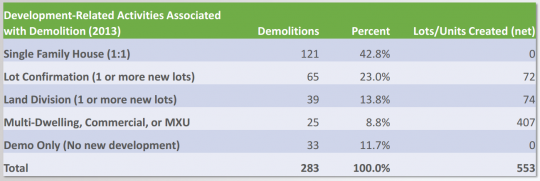

“The vast majority of demolitions that are going out at this point are one-to-one demolitions, so we’re not getting any density increase,” said Davis, the UNR spokeswoman.

City figures, however, show that demolitions have been a significant factor behind Portland’s increasing density.

Davis is right that 121 single-family homes were demolished last year to make way for new single-family homes, while only 25 were demolished to make way for apartments or other multi-family homes.

However, it only took a few demolitions to have a big impact on the central city’s supply of new housing. Those 25 homes were replaced by 432 new apartments — enough to account for 9 percent of the new multifamily housing supply in the entire four-county Portland metro area last year.

As of 2013, 47 percent of occupied Portland housing units are rentals. That’s up from 44 percent in 2000.

Homeowners ask for ‘a place at the table’

Spencer-Hartle noted that the city isn’t allowed to restrict demolitions on commercial property, only on residential. Most apartment construction in the last few years has been on commercial and mixed-use rather than residential property.

Davis said the group’s primary request is to include neighborhood associations on equal footing in the city’s policymaking about demolitions.

“It’s saying, ‘Hi, we want a place at the table,'” she said. “Right now they’re only listening to developers on this demolition issue.”

Davis said United Neighborhoods for Reform’s steering committee of 12 to 15 people consists of an eclectic group of Portlanders, all of them homeowners.

“We want it to be this process that equitably reflects the early investors,” Davis said. “And that’s us.”

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. This sponsorship has opened up and we’re looking for our next partner. If interested, please call Jonathan at (503) 706-8804.