(Photo: J.Maus/BikePortland)

Cities can’t exist without cargo. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that cities can exist with fewer big trucks.

Two weeks ago, the day after local man Kirke Johnson was killed in a collision with a right-turning semi-trailer truck that apparently failed to yield as he passed it going straight, urbanist website CityLab published an interesting bit of news.

After years of selling 15-foot cargo vans as delivery vehicles in Europe and Japan, Nissan has found a market for them in the United States, too:

“We did talk to businesses that operate in condensed urban areas,” says Bedrosian. “They were really having a tough time maneuvering within the city. They wanted a vehicle that could easily get into the city and out.”

Michael Bunce, Vice President of Nissan Commercial Vehicles, believes these smaller cargo vans may sell upwards of 75,000 units in the United States this year. “We’re getting to the point where we’re going to be more successful in the U.S. than in Europe,” he says.

Some of this is due to American small-business owners who need something bigger than their family car but don’t need a commercial truck. Either way, it’s a win for safe streets. CityLab adds:

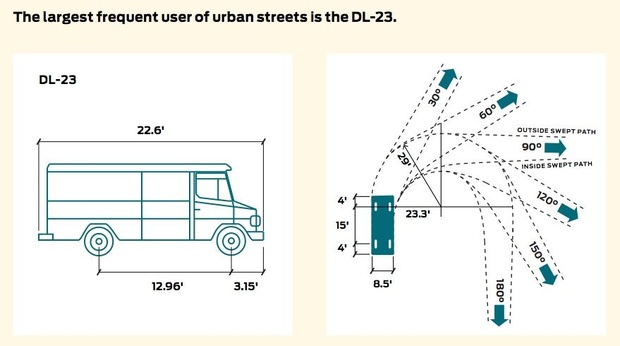

The Federal Highway Administration suggests having traditional 30-foot trucks in mind when designing residential and local city streets and intersections. But in its latest design guide, the National Association of City Transportation Officials recommended preparing for a 23-foot vehicle in such situations. The City of Chicago has followed suit; its latest street guide (with Nelson\Nygaard as lead consultant) also introduced a 23-foot delivery van for neighborhood streets.

There are really a couple different issues here.

Whether articulated tractor-trailers should be in urban areas at all. First, are tractor-trailer rigs like the ones that killed Johnson — and Kathryn Rickson in 2012, and Tracey Sparling in 2007 — compatible with central cities?

Advertisement

In Rickson’s case, the county prosecutor’s office concluded that the truck’s driver couldn’t possibly have seen her in his mirrors as he began to turn. (A civil lawsuit later called that into question.) If drivers of the biggest trucks are physically unable to see whether they’re about to kill someone, should such trucks be legal?

Another alternative, used in parts of Europe, is for big rigs to stop at the urban periphery and transfer their loads to smaller vehicles. But if so, how do we decide what is and isn’t an “urban area”?

is an increasingly popular freight option.

(Photo: Jason Lawrence)

Whether fleet changes could reduce the number of unarticulated 30-foot trucks. These are more common inside U.S. cities than semi rigs, but arguably have a bigger influence on cities because urban streets have been designed around them. You know how many street corners built since the 60s are rounded off, enabling people to whip quickly around them in their cars? The idea of designing a street around the largest vehicle that regularly uses them (30-foot trucks) seems sensible enough. But since the 60s, we’ve learned that doing this changes the natural behavior of the other traffic on the street, too, making it more dangerous 24/7.

This is why a shift toward 23-foot cargo trucks, 15-foot cargo vans, or even pedal and electric-powered trikes — in the cargo market and in urban planning — would make so much difference. Not only would it change the type of vehicles on the street, it could in the way we build streets in the first place.

(Photo: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Here in Portland, the fact that most cargo vehicles are big and dangerous to be around is a subtle influence on almost everything we do with our streets.

Last week, discussing chaotic behavior on North Williams Avenue, city project manager Rich Newlands wrote in an email that although it’d be “better” to run a concrete curb alongside a green-painted bike lane just north of Broadway, that would be impossible because of the “the turning radius of large trucks.”

Two weeks earlier, city staff recommended keeping protected bike lanes off Grand Avenue, citing the city’s policy to separate freight and bike traffic by nudging them onto completely different streets.

Like so many things about our streets, this policy is based on the assumption that in order to survive, any major commercial area requires daily visits from dangerously large trucks. But what if this isn’t actually true?