This is a guest opinion piece by A.J. Zelada, a longtime biking and walking advocate who chaired the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee from 2011 to 2013.

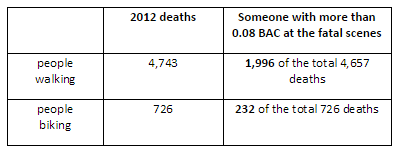

Intoxicating amounts of alcohol are at the death scene of 36 percent of walking fatalities and 32 percent of biking deaths.

So why does today’s street safety movement seem to trivialize it?

Last year, I listened to Oregon’s Safe Routes to School manager proclaim new safety issues to protect pedestrians. The ideas were great, but one was missing: She did not mention alcohol at death scenes. Vision Zero is being considered by many cities, including Portland and New York City, as a backbone policy for reducing road deaths. New York City’s new Vision Zero policy has one paragraph about alcohol.

Last year, the US Department of Transportation reported alcohol blood level was 0.08 grams per deciliter or greater:

- in the blood of 14 percent of the drivers involved in walking fatalities

- in the blood of 36 percent of people who died while walking, including more than 45 percent of people aged 21 to 54

- in the blood of 24 percent of people who died while biking

I don’t want to blame victims here. The circumstances of these deaths were all complicated. But alcohol was part of far too many of those circumstances.

What we spend ‘safety’ money on

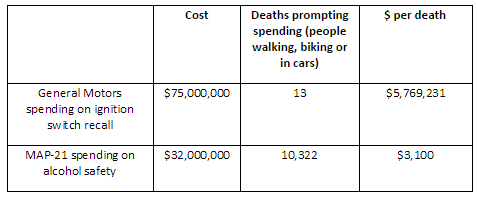

The last comprehensive federal transportation budget, known as MAP-21, included $32 million for safety programs that address intoxicated driving, young drivers, use of safety belts and child safety. It also included $5.4 million to research in-vehicle technology to prevent alcohol-impaired operation of the vehicle.

Meanwhile, General Motors has spent $75 million in their recall of 2.6 million cars associated with 13 deaths due to faulty ignition switches. A year ago, I would have applauded this and felt smugly that they deserved it. Now, I look at these numbers and I’m not so sure.

Consider this: If Alcohol, Inc., were a publicly traded corporation and associated with more than 10,000 deaths in 2012 (about a quarter of them among people biking and walking) why would money not be thrown that direction?

Why is there no public outrage? Why is there no greater accountability expected, as we have with GM?

Advertisement

External problems vs. internal problems

I divide alcohol-related deaths into two camps: external and internal. We in this society are always looking for external reasons to fix things: recall the cars; blame the drivers; blame the road conditions. And yet we only provide $32 million for 10,000 alcohol-related deaths.

There are external issues here: Late, dark-night deaths are often low-income workers at the end of restaurant shifts. Deadly environments may have poor lighting or no sidewalks. There may be an absence of public transportation. Our own Barbur Boulevard is known as “Alcohol Alley” by some Portland police.

But even eliminating the 14 out of 100 drivers who are drunk in fatal walking crashes would not eliminate the problem of alcohol. For every 100 people killed while walking, 36 would still have been drunk themselves. Let’s analyze the reasons.

When 36 percent of people who die while walking have high levels of blood alcohol, it means that internal choices and issues of self-responsibility are not being addressed. Again, this is not victim-bashing. And it’s not anti-alcohol, either. But internal issues need a very different approach than redesigning the landscape, having special driver-key ignition systems in place, etc.

The heart of the issue: how do we teach self-responsibility? We need a cooperative blend of professionals from health, sociology, educators, philosophers, humanists. Perhaps we should adopt a stance similar to cigarette taxes, which are used for chronic obstructive lung disease costs. Consider a percent of alcohol taxation that would go to invest in safety solutions that are about behavior, not about landscape. We need more than a feel-good “let’s get the bad apples off the road.”

If Portland or Oregon adopts Vision Zero, I hope it will include a Vision 0.08 paragraph: one that includes a serious analysis of alcohol. We need real mechanisms to measure and analyze data from our alcohol-related deaths, which would include direct programs on external issues like road design, but a major focus on the internal factors behind more than a third of vulnerable road users’ deaths.

Earlier this month, A.J. Zelada wrote for us that Portland needs to invoke the “lifeboat rule” when it comes to bikeway design.