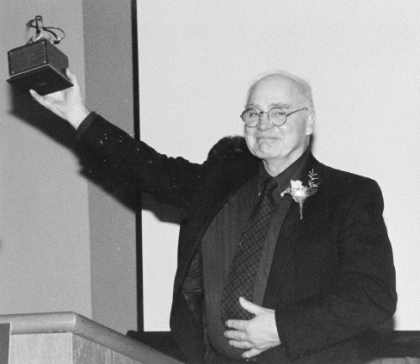

received a Bud Clark Award for lifetime achievement

from the Bicycle Transportation Alliance in 2001.

(Photo courtesy BTA.)

An often-forgotten forefather of Portland’s street-level bike advocacy movement died last week.

Sam Oakland, an English professor, poet and author who rode his bicycle to work at what was then Portland State College, started rallying bicycle riders to attend City Hall hearings in the late 1960s and led citizen actions in support of Oregon’s groundbreaking 1971 Bike Bill.

“There just wasn’t a lot of advocacy going on at that time,” said Karen Frost, who followed in Oakland’s steps 25 years later as the first executive director of the Bicycle Transportation Alliance. “He was really kind of a prime mover.”

He called his volunteer network the “Bicycle Lobby,” and referred to himself only as its “clerk.”

Scott Cohen, a city transportation bureau staffer and student of local transportation history, said his impression is that Oakland’s group was “the Shift of the 1970s.”

Local historian Steven Reed Johnson has this account of a rally organized by Oakland, then 36, in November 1970:

400 bicycle enthusiasts gathered on Swan Island in North Portland to draw attention to a four-point petition that Oakland had written. The petition called upon the city to create bike lanes on major thoroughfares and bridges; bike parking facilities near schools, department stores, supermarkets, restaurants and in city garages; bike racks on city busses; and the consideration of bike lanes and parking facilities in plans for future developments within the city.

Frost, who researched Oakland’s work as part of a 2001 event that marked the 30th anniversary of the bike bill, said Monday that in the days before email databases, Oakland used handwritten posters, word of mouth and bike activism’s longtime secret weapon — bike rides — to make Portland riders a political force in the lead-up to the 1970s bike boom.

“There was a constituency of bicycling at the time, and that grew out of the fact that it was easy to bike,” Frost said. “You know how Southeast Portland is.”

According to Johnson, Oakland calculated in 1971 that 400 people bike-commuted into downtown Portland daily.

The 1971 bike bill, which required bike facilities as part of all major road projects and set aside 1 percent of state transportation spending for bike-specific facilities, was the first of its kind in the country and is widely seen as putting Oregon on its slow path to becoming by far the most bike-friendly state in the union.

In Salem, the bill was championed by the late Don Stathos, a Medford-area Republican who convinced a reluctant Gov. Tom McCall to endorse it. It passed the legislature by one vote.

While Stathos managed the inside game, Oakland activated Portland riders, gathering a reported 15,000 signatures in the bill’s support. The city, meanwhile, appointed him to chair its first citizens’ bike committee.

Oakland pulled back from bike activism during the 70s and 80s, but stayed active in local politics. As the Oregonian reported in an obituary Monday, he ran for office many times, never successfully, and taught or studied in Macedonia and Siberia before retiring from PSU in 1985.

Rex Burkholder, co-founder of the BTA, said Monday that he learned of Oakland and his work when Oakland “showed up in the BTA office in the 90s and introduced himself.” Longtime Oregon biking advocates Michael Ronkin and Karen Swirsky said Monday that they knew of Oakland but had few details of his grassroots work.

“You always feel like you don’t know the history,” Burkholder said. “Because they didn’t put you in the history books.”

When he died last week at age 80, Oakland was preparing for Peace Corps service in Albania.

Prof. Tony Wolk, a colleague of Oakland’s in PSU’s English department, said Monday that when he decided to start riding his bike to work, right around New Year’s Day 1969, it was Oakland who taught him the routes to get to PSU.

“Now, thanks to Sam, I’ve put over 60,000 miles on my original bicycle and I’m still riding it,” said Wolk, 78. “Sam was very helpful in that way, and I think he was key on getting things going in the city of Portland. He was, like, the first one over the hurdle.”