(Graphic by Roger Geller, Portland Bureau of Transportation)

Roger Geller, one of the most respected bicycle professionals in North America, was not having a terrific afternoon. His baritone had slid up to a tenor.

“This is beneficial,” he said to the roomful of owners of retail businesses along 28th Avenue near Burnside, gathered at Coalition Brewing Wednesday afternoon. “This is a good thing for your business district.”

Portland’s bicycle coordinator for the last 14 years — a confident and amiable man, but always known more for his groundbreaking analyses and head for numbers than for a silver tongue — was pitching the benefits of replacing auto parking on one side of the street (including a couple blocks in each direction, it’s maybe one-eighth of the district’s auto parking) with a buffered bike lane. Geller made one argument after another as to why there was no reason to think the district would suffer. But for each fact he cited, someone had an immediate rebuttal.

“Those parking spots are dear,” one man at the bar said, to wide agreement. “The very limited parking that remains in this district is really being stressed.”

“Is it the City of Portland’s job to reduce people’s use of their cars?” one woman asked. Geller didn’t answer directly.

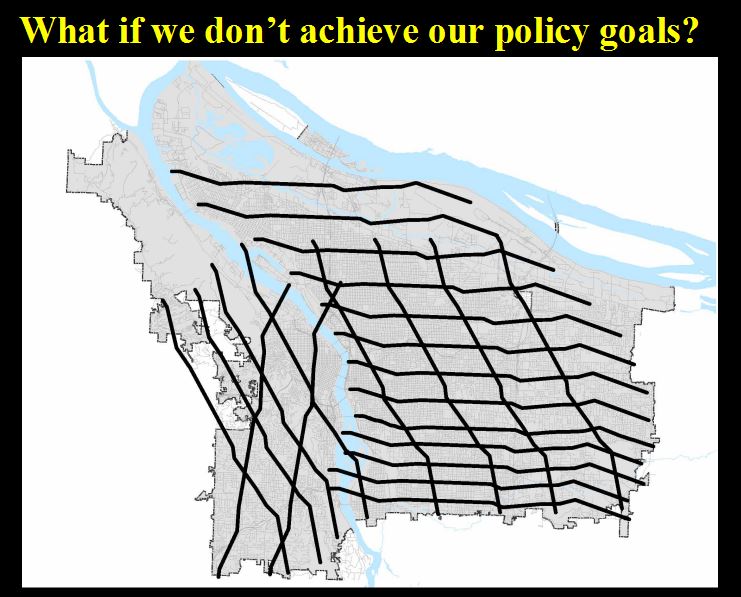

But in response to a different question about future traffic patterns, Geller flipped to a new page in his presentation and showed his audience a map that, for a moment, seemed to leave them quiet.

It was a picture, he explained, capturing what Portland would need to look like if it doesn’t decrease the likelihood that people use cars for their errands and commutes.

“Powell Boulevard carries 45,000 cars each day, more or less,” Geller said. If Portlanders keep driving cars as much as they do now, he noted, and if the Portland’s area’s population grows by the 1 million people that Metro expects it to by 2035, the additional auto capacity needed would be the equivalent of 23 new Powell Boulevards lacing through the city.

Everyone looked at the maps for a second. And everyone seemed to understand exactly what they meant.

The moment of silence didn’t last long. The conversation moved on to other, more easily rebutted details. Geller’s proposal still lost an advisory straw poll of attendees, with two in favor, five undecided and 10 opposed. But of all the arguments Geller made on Wednesday, it seemed clear that this one had hit closest to home.

I’m just a journalist who was covering the event for this site. But the reason this idea had power, it seems to me, is that it was the only one that really forced the people in the room to confront the long-term choices faced by Portland, and by every growing city.

Here’s the thing: we already tried Plan A. Portland’s 40-year experiment with auto dependence, from 1940 to 1980 or so, didn’t work any better than any other American city’s did. It turned the east half of the city into a husk.

In the long run, a growing city can hollow itself out to make room for more and more cars. It can spend tens of millions on three-story parking garages and hundreds of millions on wider streets and freeways. It can build parking lots that push every destination further from the next, further increasing the need for cars. It can deal with the noise, pollution, danger and expense that all those cars and hours behind the wheel create.

Or, alternatively, it can make it desirable for people to more frequently get around in ways other than cars.

And here’s the thing: we already tried Plan A. Portland’s 40-year experiment with auto dependence, from 1940 to 1980 or so, didn’t work any better than any other American city’s did. It turned the east side of the city into a husk. People who could afford to move to suburbs did so.

It’s a time that many longtime Portlanders, including most of its business owners, probably remember. In fact, one of the owners, John Taboada of Navarre restaurant, had alluded to it just a few minutes before Geller had flipped to his map.

“15 years ago, it wasn’t that great,” Taboada said of the 28th Avenue district. “There was a parking lot and a blood transfusion center.”

Taboada, who said his top concern is auto travel speeds, is still undecided about the city’s proposal. But he’s only one of the many people in the 28th Avenue district — entrepreneurs, landlords, residents — whose future depends on its continuing to be a place people want to spend their time, even if the parking is a hassle.

If we don’t keep making bicycle transportation in the city more efficient, safe and simple, will that be possible? That’s the choice Geller’s presentation forces every Portlander to think about.