(Image: LiveMove)

When we explored four reasons college towns tend to be bike-friendly last month, we left one off: they produce lots of technical experts who are passionate about improving their communities.

It looks as if a group of Eugene students is likely to do exactly that. After nine months of volunteer planning, the University of Oregon group LiveMove has unveiled a plan for their city’s second two-way bike facility, and the city government is officially considering it.

The plan is for 13th Avenue, a one-mile one-way corridor between the UO campus and Olive Street in downtown Eugene. The east-west route has a bike lane, a bus line and various commercial storefronts.

“We were biking down 13th every day and we were sort of noticing that there seemed to be a lot of people biking the wrong way or skateboarding the wrong way,” said Alex Page, a spokesman for LiveMove who gets to campus on a bike himself. “The corridor between the campus and downtown doesn’t work for most people, whether or not they’re driving, whether or not they’re riding transit or biking. People find it unsafe and not direct.”

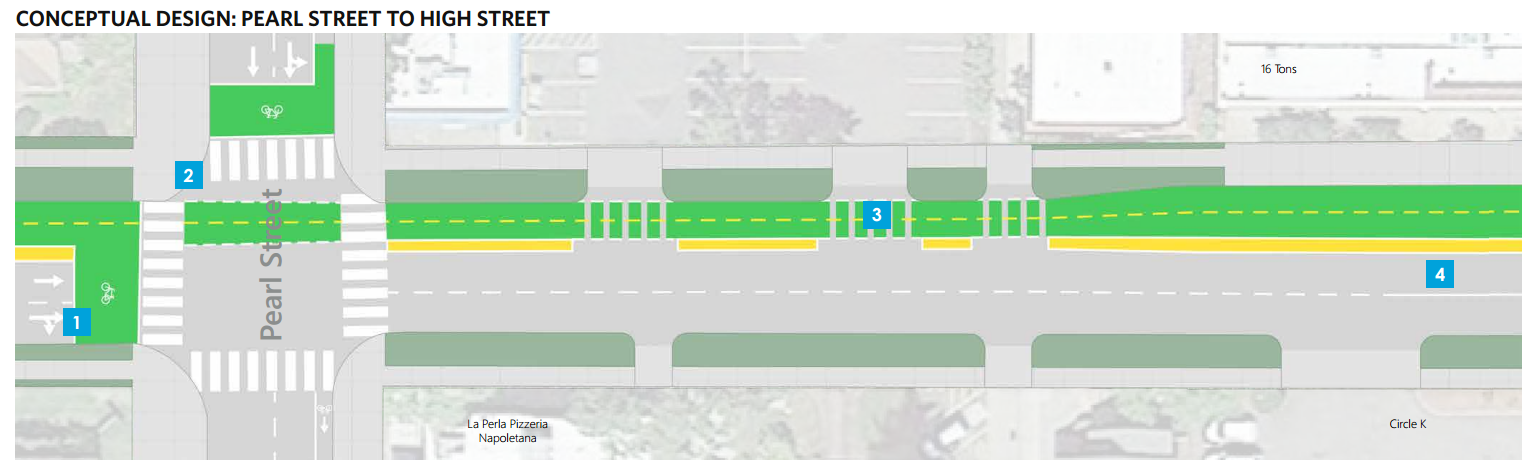

LiveMove’s alternative concept would use solid green paint with stripes or green bike boxes at intersections, plus a yellow-painted buffer zone to separate bike and car traffic.

The proposal got a boost over the summer when Susan and John Miner, whose son David was killed in 2008 while riding his bike at 13th and Willamette, offered to put up $150,000 to support the project.

“On their own, they approached the mayor and said, ‘You should look at this,'” Page said.

LiveMove was funded several years ago by the same federal grant that created OTREC at Portland State University. It’s organized by a multidisciplinary group of interested planning students who Page said focus on “alternative modes of transportation, more livable communities, however you want to define that, and just leading people off of automobile dependency.”

Page said the group tweaked its design by observing which parking spaces on 13th were actually being used heavily and which were not. They took steps to preserve the most popular ones.

“For us, it’s not about bikes. For us it’s about a sensible use of public space.”

— Alex Page, LiveMove spokesman

“Each year we tend to do a few small programs or projects around campus or around the community,” said Page, 29, a community and regional planning graduate student. “For us, it’s not about bikes. For us it’s about a sensible use of public space. … There’s a balance that we can strike where we use the roadways equally and fairly. Part of that comes from, I would say, our philosophy as planning students saying that this is a public space. It should be for everyone.”

The 13th Avenue bikeway would have a dedicated bike signal phase at its downtown end, and would meet the campus (and the similar, perpendicular two-way buffered bike lane) at Alder Street.

On its website, LiveMove explains that their design “is not only for the current bicycle commuters who feel the roadway does not work for them, but for those “would-be” cyclists who have legitimate fears about bike commuting.”

We’ve seen similar efforts here in Portland such as the Swift Planning Group, a team of PSU students who early this year came up with a plan for redesigning North Lombard Street, but I’m not aware of any plans of this scale that have been successfully adopted by a government here in Portland. The City of Eugene plans to return to the public with a proposal in February.

In one way, this effort highlights one of the biggest barriers to better bike infrastructure in the United States: it takes work. Custom-designing 10 intersections to be safe for separated bike and car traffic required nine months of part-time unpaid labor from a team of near-professionals. Though seasoned traffic engineers could do this work far more efficiently, a bikeway like this isn’t something a planner can dash off in a day or a week. If bike projects like these are going to become common, we won’t be able to count on talented volunteers to provide the labor. We’ll need to be willing, as a society, to pay for the work required, which of course is far cheaper than a car project that would move a similar number of people.

Page said he thinks cities can prioritize projects like these if they choose to.

“It took a lot of our collective effort,” he said. “But it’s not like they’ve never been done before.”

In any case, let’s congratulate LiveMove on their success so far and hope it adds up to an idea that turns out to be right for Eugene and its increasingly public streets.