and pleasant for humans in part because

it was developed as a streetcar suburb in the 1910s.

(Photo: M. Andersen/BikePortland)

One of the big annoyances of getting around Portland’s inner east side by bike is the shortage of good ways to get north or south. A project that could become Portland’s best such link (and might thereby improve the route for driving, too) is about to kick off.

The project won’t reach its full design for a year, but it already has a few detractors, and there are a few significant hurdles on the horizon. After a reader tipped us off about neighbors who are concerned about how the project will impact parking and auto access, we figured it was time to check in and bring you up to speed.

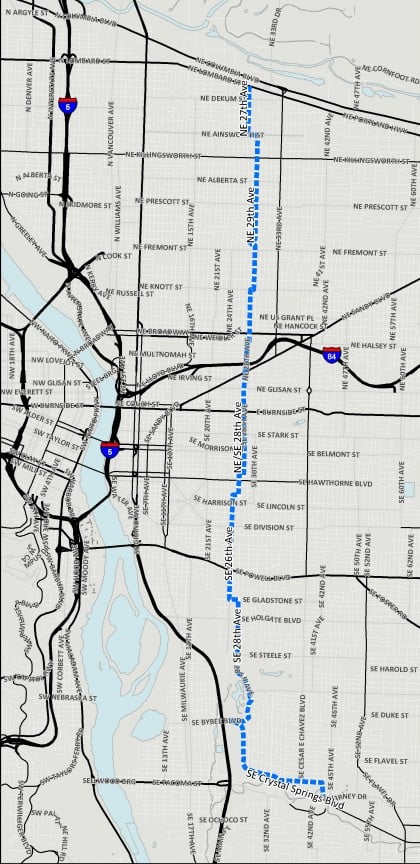

The 9.1-mile 20s Bikeway Project is one of the centerpieces of the Bicycle Master Plan passed in 2009. Right now, it’s mostly just a line on a map, a federal grant for $2.5 million, and a target completion date of 2015.

The route connects Northeast Lombard Street to the north and the Springwater Corridor to the south, running directly through many of Portland’s fastest-growing neighborhoods, plus Reed College, Concordia University, Grant and Cleveland High Schools and two major grocery stores. It’s already a very popular bike route due to the lack of alternatives, but it’s not much fun for most people to use that way:

it lacks dedicated space for cycling and is uncomfortable for less confident riders.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

City Project Manager Rich Newlands said Tuesday that the route might be tweaked, but that the bikeway is too important to do without. He’s halfway through collecting traffic counts on the corridor.

“Clearly, for it to be a high-quality bikeway, we’re going to need to make improvements to enhance safety for cyclists,” Newlands said.

The grant will improve the bike crossings of Interstate 84 at both 28th and 21st Avenues, which are arguably the best two such crossings in the city. But the main 20s route, Newlands said, will run over the 28th Avenue bridge.

Just north of that bridge and south of Broadway, there’s a particularly difficult corner — a blind turn for northbound traffic that can hide a person on a bike from someone in a car:

Further south, between Sandy Boulevard and Stark Street, is one of the east side’s liveliest commercial districts, with crowded, city-sponsored auto parking on both sides of the street and two lanes of shared traffic that often back up along 28th Avenue.

Between Southeast Division and Taggert, there’s another popular commercial district, and another notable lack of bike lanes:

More sticking points might emerge. At the southern end of the route, some people from the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association (notably the group’s president Robert McCullough, who sat on the committee behind the City Club of Portland’s recent report endorsing Portland biking and was one of two members to endorse the “minority report” calling for bike licensing) are worried about traffic safety and loss of publicly provided auto parking.

In a post on the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association Facebook page, McCullough wrote that his neighborhood’s representation on the project’s advisory committee should not be considered a “fait accompli” in terms of their support. “Although Eastmoreland residents have bicycles,” wrote McCullough, “the average age is above 50 and increasing four months each year. This makes the area car rather than bicycle centric (bicyclists tend to be you white males in their 20s). Obviously, “calming” access to the west would make many residents unhappy. It might also slow police and fire response coming from the west.”

Newlands said he expects the solutions to all these problems are likely to include a combination of striped bike lanes, neighborhood greenway style sharrows and speed bumps on low-traffic streets, and possibly separated cycle tracks on the busiest stretches.

Newlands says he’s currently recruiting stakeholders to join a committee that will meet for four to six months starting in October, aiming to finish next year with a plan endorsed by neighborhood and business associations. This would let the bikeway be completed by 2015.

“I’m mildly confident that it’ll be a sufficient amount of money that we’ll be able to do what we need to do,” Newlands said. “But, again, it all depends on what kind of issues we find during the plan process.”