There’s a quiet revolution going on in the field of transportation research. A new guard of young students and up-and-coming professionals are infusing new life and ideas into a body of work that has long been dominated by auto-centric research. They’re the people we’re turning to more and more to answer important questions like; Do bike boxes work? How much auto exhaust do people breathe while bicycling? How does our mode of travel impact spending patterns? And so on.

Portland State University’s urban planning school and the Oregon Transportation Research and Education Consortium (which funds much of the research) is at the forefront of this burgeoning field of study.

Many PSU planning students completed their pilgrimage to the annual meeting of the Transportation Research Board (TRB) which wrapped up last week in Washington D.C.. At an event dubbed ‘TRB Aftershock,’ held last night during happy at a brewpub in northwest Portland, members of PSU’s Students in Transportation Engineering and Planning Club presented their TRB papers for those of us who couldn’t make it to D.C.

When I showed up to the event, the first conversation I had was about a debate over whether the standard and accepted walking speed should be calculated at 3.5 feet per second (which is used now) to a lower speed that favors more humane road design and signal timing. I knew I was in for an interesting night.

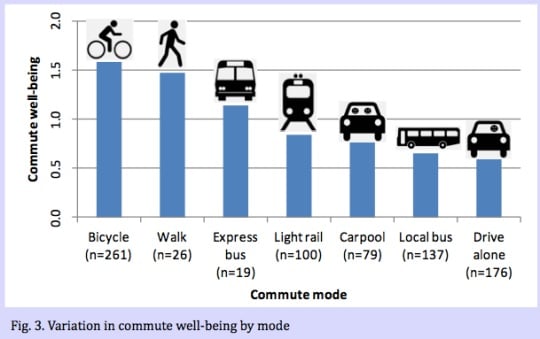

Then I met Oliver Smith, a Ph.D. Candidate in Urban Studies at the Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning at PSU. Smith recently completed a research project titled, Commute Well-being Among Bicycle, Transit, and Car Users in Portland, Oregon (PDF of presentation poster) Based on surveys from 828 people taken during January through February of 2012, he found that commuting to work under your own power “increases commute well-being.” In other words, the happiest commuters are those who walk and bike. Of course I was happy to see that of all modes surveyed, biking made people the happiest (see chart). The lowest measures of commute well-being were recorded by people who drove alone (which is unfortunate because 58% of Portland commuters get to work that way).

Smith’s research also found that people who make over $75,000 per year, and people who are happy with their job and housing situation were more likely to report a high commute well-being. Major factors that dragged down well-being scores included traffic congestion (non-existent for bike riders), crowded transit vehicles, safety concerns (especially for bikers), and travel times longer than 40 minutes (for auto drivers only).

Another bit of research that caught my eye was titled, Modeling Children’s Independent Walk and Bike Travel to Parks and School (PDF of presentation poster) by PSU Ph.D. candidate Joseph Broach and professor Jennifer Dill. The goal was to better understand why fewer kids are walking and biking without their parents these days.

Children aged 6-16 and parents from 323 Portland households were asked questions about travel behavior, perceptions of their neighborhood, perceived social norms, socio-demographics, and so on. Broach and Dill found that, when it comes to kids going it alone in the neighborhood, proximity matters, especially for travel to parks. The average child was nearly three times as likely to walk or bike to a park that is 1/4 mile away from home than one 3/4 a mile away. The practical implication of this, said Broach, is that, “Pocket parks are a big deal.” Pocket parks, like the one created recently on NE Holman Street, are small, neighborhood parks usually built into an existing streetscape.

Gender also played a role in Broach’s research. He found that girls are disciplined with “stay in sight” rules by their parents for an average of 1.5 years longer than boys. Girls were also less likely to travel to parks without their parents (there was no gender difference in school travel rates).

As you might expect, peer pressure also impact biking behaviors among 11-16 year olds. The research found that as children aged, there was a higher probability that wearing a helmet was a barrier to riding. Kids were more likely to bike to school and the park when members of their peer group did so as well.

These papers offer insights that often promote, validate, or refute existing policies. They also influence what types of infrastructure we build. Learn more about transportation research being done here in Portland by visiting OTREC’s website.