Safety Summit that Mayor

Adams has presided over.

(Photos © J. Maus/BikePortland)

Mayor Sam Adams and PBOT held the sixth annual Transportation Safety Summit at Jefferson High School in North Portland last night. The event was created by Adams to accomplish several things: to convene the myriad organizations and agencies that work on safety issues; to glean the best ideas from the brightest advocates and citizen activists; to tout PBOT’s accomplishments; and to validate his belief that safety should be the #1 transportation priority.

Despite what seemed (at least to me) like a smaller and less enthusiastic crowd than last year (many of the 90 or so people in the crowd were agency/City staff and there were only a handful of citizens) — the night was a success on all those accounts.

“No matter which way you slice it, the important work that we are doing together to make our streets safer is having a significant and positive impact for our city.”

— Mayor Adams

This year the summit came at interesting time. Mayor Adams has come under fire from The Oregonian for what they see as his tendency to favor “bike routes” and other expenditures over large-scale paving projects on major streets. After Adams defended his decisions in an op-ed based on his “safety over smoothness” policy, The Oregonian than Politifacted him and found his statements to be only “half-true.”

Undeterred, Adams doubled down on his commitment to safety last night, presenting slide after slide of proof that because of decisions he’s made, fewer people are dying and being seriously injured while moving around Portland. “No matter which way you slice it,” he said, “the important work that we are doing together to make our streets safer is having a significant and positive impact for our city.”

But, while Adams could point to a downward trend in fatalities in the past decade, he acknowledged that 2011 was a “mixed bag.” 19 people died while driving cars in Portland last year — the highest total since 2006. Also, more people died riding bikes (2) and motorcycles (7) last year than in 2010.

One of those two fatal bicycle collisions happened on SE Division, one of the high crash corridors PBOT is currently focusing on. As Adams spoke about it, the family of victim Dustin Finney looked on. Dustin’s mom Kristi, his sister Jenna, and his father Glen sat in the center of the crowd and served as a tragic reminder of why everyone was at the event.

Beyond the human toll, unsafe streets where collisions are common also sap our economy. Adams shared that each year, traffic collisions cost Portland $100 million in health care and productivity losses. Collisions are also the #1 cause of job related deaths, they cause 40% of all congestion in Portland injuries sustained from them “represent the highest claim category of worker’s compensation claims.”

While Portland has a lot to be proud of when it comes to safety, there is indeed a lot more work to do.

A key member of the traffic safety team in Portland is ODOT. They manage many of the roads we travel on every day. Jason Tell, ODOT’s Region 1 (that’s us) manager, spoke after Adams and he detailed some of their recent projects. Much to my surprise, Tell announced that ODOT plans to install their first-ever green-colored bike lane on southbound SW Barbur Blvd prior to the Capitol Highway on-ramp (separate story coming on this later).

Tell also reminded the crowd about AskODOT, their answer to PBOT’s beloved 823-SAFE system. If you see an issue on an ODOT-maintained road, call it in to 1-888-275-6368 or email askodot [at] odot [dot] state [dot] or [dot] us.

After updates from Adams and Tell, the event moved into a format of questions posed to the audience, followed by discussions spurred by citizens and by expert panelists. Each person in the room was given a remote clicker to respond to the questions and then the responses were instantly shared. (When the results of a poll about the ethnic background of the crowd came back as 80% White/Caucasian, there was a collective gasp in the room.)

Much of the discussion centered on PBOT’s High Crash Corridor safety program, a program began with the 82nd Avenue of the Roses project in 2006 and now includes focused efforts on Marine Drive, SE Division and SW Beaverton Hillsdale Highway.

Why focus on high crash corridors? Despite large and busy streets making up only 30% of Portland’s network, they account for 70% of serious injury collisions.

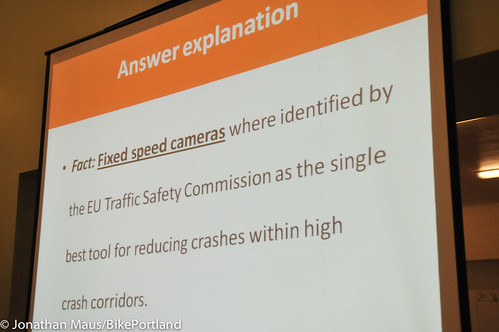

The problem of these big and busy streets is obvious: people drive too fast on them. What’s not clear is how best to curtail that behavior. According to City Traffic Engineer Rob Burchfield, simply adding crosswalks won’t help, neither will signs stating a lower speed limit. Judging from a series of questions asked by PBOT last night, the City seems to be keen on an enforcement mechanism called “fixed speed cameras.”

When people were asked to vote on which strategies the city should pursue to reduce collisions on busy streets, the number one response was, “Improved pedestrian and bicycle facilities.” 66% of respondents chose that option, while 55% said “Road Diets – Reducing Lanes” and 51% voted for “Fixed Speed Cameras.”

Then, seemingly to boost their case, PBOT asked which method was found to be most effective by a recent report from the European Transportation Safety Commission (for some reason, the bike facility option wasn’t an option). The answer? Fixed speed cameras.

And then, taking their case for speed cameras even further, they asked the question: “Should the traffic safety community pursue the authority of local governments to use automated enforcement in urban high crash corridors?” Not surprisingly, a whopping 81% of the people in the room thought they should.

Currently — as described by one of the biggest supporters of these cameras, BTA Executive Director Rob Sadowsky — the City of Portland must have a police officer present when they use speed or red-light enforcement cameras. A law that would allow for the use of “fixed” location cameras would do away with that requirement, thus opening up their use. Many see these cameras as the best tool to get people to slow down and the fact that they would create a new revenue stream to pay for traffic safety projects is sweet icing on the cake.

But funding and legal hurdles aren’t the only barriers for using speed enforcement cameras. They are mired in a public debate about privacy. “We have to overturn the mentality,” said Sadowsky, “that people’s privacy being invaded is more important than the law.”

Stronger enforcement is just one part of a “Vision Zero” concept that is gaining steam locally. The basic idea, says Sadowsky, is to change the culture so that people behave on every street they use as if they themselves live on it. Is it realistic to ever get to zero traffic fatalities? “It wouldn’t be moral if we didn’t think so,” said Sadowsky, “Our society should no longer have a tolerance for a fatality… And that’s what vision zero is all about.”

Those words were very comforting to Kristi Finney. At the end of the event, she stood at the front of audience with a box of her son’s ashes in her hand and spoke:

“At first I thought it was a drunk driving issue… and then when I learned more, to me it kind of became a bicycle because I was very shocked at the number of people who blamed my son just because he was riding a bicycle. Since then, I’ve done a lot of research and I’ve discovered it’s just a people issue; a transportation issue.

I was feeling pretty hopeless in the first half of this discussion because what I was seeing and hearing was a bunch of people here who want to make changes and government officials who want to make changes, and then the majority of people who need to be here listening to this, they’re not here and they’re just complacently going about their lives because a tragedy hasn’t affected them yet.

I was feeling pretty hopeless, because it sounds like we have to force people to do the right thing, and we don’t have the money or resources to do the right thing. But I was very greatly uplifted by Rob [Sadowsky] who said that he can see it happening. So was thinking of myself I’d like a tape of that so I can play it over and over — ‘It can happen, it can happen, it can happen.’ I don’t want anyone else getting that phone call or that knock on the door at five o’ clock in the morning.

So my goal for my son Dustin and the rest of my family is to help people realize that it can happen to them. I don’t want anyone else to have a story like mine.”

[I’ve got more to share from this event, but I’ll leave it here for now.]