It’s been over a year since the Community Cycling Center embarked on an effort to better understand why Portland’s bike riding masses lack racial diversity.

In a story published here back in October, CCC executive director Alison Hill Graves said, “The people riding and making decisions about bicycles is a white, middle class group.”

Yesterday at a brown bag discussion hosted by the City of Portland Bureau of Transportation, Graves presented initial findings from their Understanding Barriers to Bicycling project.

“It’s not a great place to live for everybody. Some people don’t really live in a livable community.”

— Alison Hill Graves, executive director of the Community Cycling Center

On Thursday, Graves pointed out that while Portland is heralded for its livability, not everyone has the same access to it. “It’s not a great place to live for everybody. Some people don’t really live in a livable community.”

As evidence, Graves shared the “Equity Analysis Gap” graphic from the Portland Bicycle Plan for 2030. That analysis (which was done at the behest of Graves and others on the plan’s equity subcommittee) shows a striking correlation: areas with the most ethnic diversity have the most gaps in the bike network.

As Portland adds a million people in the next 20 years, Graves explained that 60% of them will be of hispanic descent. “We often hear, ‘if you build it, they will come,’ but who will come?” Graves says if we don’t do more to connect and engage with communities of color, Portland’s biking future will remain dominated by a white, middle-class demographic (and it will never look like the mural outside the CCC bike shop on NE 17th and Alberta, which Graves said embodies their vision).

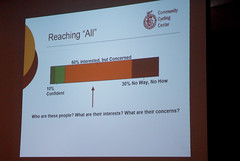

To create relationships and get to know people in these communities, the CCC (with both staff and outside consultants) had 75 meetings, attended neighborhood events, and held five open houses. The CCC focused on two affordable housing developments; New Columbia in North Portland and Hacienda CDC in Northeast.

After speaking one-on-one with over 150 people, Graves says three main themes emerged as barriers to biking: the cost of bikes and their upkeep, concerns about safety, and the logistics of riding (where to do it, what the rules are, and so on).

The bad news, reported Graves, is that many people do not feel safe riding in their neighborhoods. Related to that is fear of bike theft (due to a lack of secure parking areas). She also pointed out that much of the information produced by the City of Portland, Metro, and advocacy groups is not getting through. “Many of them didn’t even know Portland was a bike city, or that bike maps exist”.

There were also very strong cultural perceptions working against bikes. “Only kids rides bikes” and “bikes are for white people” where among the statements the CCC recorded from the interviews. Bikes were also considered symbols of gentrification — a painful subject for many residents of North and Northeast Portland.

In one of the more interesting findings, 43% of Hispanics interviewed said they wouldn’t ride a bike because they were afraid of getting pulled over by police.

Graves says the good news was that there was, “A lot of agreement that biking makes sense to increase and improve individual health.”

From here, the CCC will return to the partner sites for monthly rides, classes, bike clubs for kids, and so on. They’ll also develop “working groups” at each site to “engage leadership, leverage partnerships, and increase ridership”. There will also be a focus to identify and then remove policies that make biking difficult.

Graves is aware that this issue is much too large and complicated to fit nicely into a non-profit group’s program. But she says they’ve approached it with realistic expectations. “We’re only a year in on this project, we have a long way to go.”