presented the new cycle track to

the bike advisory committee

at City Hall last night.

(Photos © J. Maus)

Last month, when Mayor Adams and the Bureau of Transportation announced the new, cycle track pilot project on SW Broadway, many people in the community were excited. The removal of an entire lane of auto traffic on a marquee downtown street just to create more space for bike traffic was cause for celebration in bike circles.

However, it wasn’t all smiles in Bikeville and some people raised concerns about the new facility.

The concerns seemed to be primarily about how folks would negotiate a left turn out of the cycle track (bikes are separated from motor vehicle traffic by parked cars), and how the cycle track (a new facility type not specifically defined in Oregon statutes) would jibe with existing traffic laws that govern bikeways.

Since the plans were announced, I’ve discussed these issues with Adams’ Transportation Policy Director Catherine Ciarlo, local bike lawyer Mark Ginsberg, and City Traffic Engineer Rob Burchfield. Burchfield also presented about the project at the monthly City of Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee meeting last night.

“We need to learn and get a sense of how this functions for people. This left turn issue is a really important question that we need to sort out.”

— Catherine Ciarlo, transportation policy director for Mayor Adams

Left Turns

Since the new cycle track puts bike traffic in its own lane (completely separate from auto traffic) many people wondered how they would make a left turn out of the facility. With the existing bike lane, most people simply signal, leave the bike lane a bit prior to the intersection, and then veer to the left to make the turn.

Catherine Ciarlo in Mayor Adams’ office said things will be different with the cycle track. “The design doesn’t anticipate someone leaving the cycle track,” she said. According to Ciarlo (and Burchfield), there are two main ways folks would make a left turn.

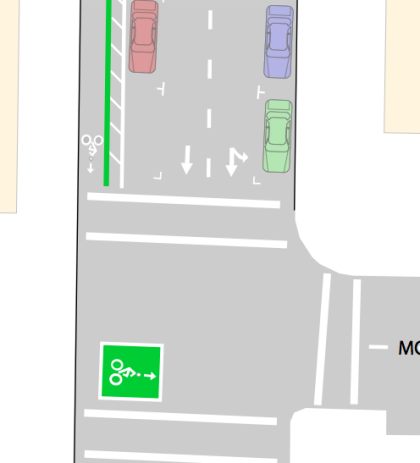

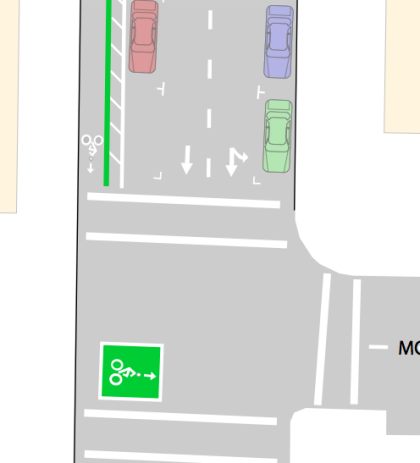

The first is to use a new bike box and perform what bike planners call a “two-stage” left turn. Note the proposed design in the drawing below:

Riders on the cycle track (shown in the upper left above) that want to go left would cross through the intersection, position themselves in the bike box, and then go across when the light is green (there would be a new “No Turn on Red” sign for cars turning from the bottom right corner of this drawing).

City traffic engineer Rob Burchfield, a regular bike rider himself and part of a delegation that went on a bike study tour of Amsterdam and Copenhagen last year, said the bike box will feel very safe for people on bikes, because it will be “in the shadow” of parked cars. In the drawing above, you can see what he means. The car parking is aligned with the edge of the bike box, so this will allow bikes a bit of breathing room, out of the way of moving cars, while they wait to cross.

The other way to make a left turn would be to anticipate your move at least a block prior. So, if you wanted to turn left at SW Montgomery, you should leave the cycle track a block before, at SW Mill, then proceed to take the lane in preparation for your left-hand turn.

Burchfield and Ciarlo both stress that they’re not sure how riders will use the facility, but that’s why this is a pilot project. “We need to learn and get a sense of how this functions for people. This left turn issue is a really important question that we need to sort out,” said Ciarlo.

As for right turns, there happens to be only one on the entire, seven block stretch of this cycle track (that’s one reason PBOT picked this location). Last night, Burchfield said they’re still looking at how best to handle those situations.

Legal Considerations

Since the cycle track design is new in Oregon, there are some grey legal areas that need to be addressed and worked out. One of the big concerns that commenters shared after the plans were announced was whether or not they’d be legally “forced” to use the cycle track facility.

[Note: Lawyer Mark Ginsberg, who has worked many bike-related traffic cases, said it will be important how the city identifies the cycle track. Will it be considered a bike lane or a path? (Those words have very different legal standings.) According to Burchfield, the city will consider the cycle track to be a type of bike lane.]

“If the City believes it is a type of bike lane, they need to clearly communicate that with the enforcement agencies and with the community so that people know how to operate in it.”

— Mark Ginsberg, bike lawyer

The concern over being forced to ride in the cycle track comes from Oregon Revised Statute (ORS) 814.420 that says a person must use a bike lane when one is present. There are exceptions to this statute. You can legally leave a bike lane to safely pass another vehicle, to “prepare to execute” a left turn, or to avoid debris or hazards.

The statute also states that a person is not required to comply with the rule unless the responsible jurisdiction has established, after a public hearing, that the bicycle lane or path is “suitable for safe bicycle use at reasonable rates of speed.”

City engineer Burchfield is meeting today with the City Attorney and the Police about how this part of the bike lane law would work. He said, “We need a decision on whether we maintain flexibility for bikes to operate in the [motor vehicle] travel lane and are not required to use cycle track. We may be able to do that in existing law by holding a hearing and finding that that [leaving the cycle track to make a left turn] is a safe way to operate.”

Ginsberg, well aware that legal cases often revolve around semantics, says his primary concern is that, “If the City believes it is a type of bike lane, they need to clearly communicate that with the enforcement agencies and with the community so that people know how to operate in it.”

On the issue of legal concerns, Catherine Ciarlo in Mayor Adams’ office said this is what comes with being innovative. “If we were to spin out every possible scenario that would happen legally in the future, we wouldn’t be able to innovate,” she said, “So our job is to put something out there that is as safe as we can possibly make it, then to watch carefully and evaluate how it’s used, get feedback from cyclists and others and then make changes, adjustments and additions to the system moving forward based on that.”

Ciarlo sees the cycle track as being directly aligned with the City’s bike-friendly goals. “One of our strong city policies is to dramatically increase the number of people bicycling. The way we can do that is to build facilities that feel safe to less experienced riders. We hear from countless people around the city who don’t ride because they are afraid, and that’s what this is targeted at.”

At the end of his presentation last night, Burchfield stepped back from the wonky details and offered some context about what this cycle track means to the City: “If we’re headed toward a future where more of our mode split is bikes and fewer people are driving cars, then this project is symbolically a big step to take.”

— The City has created an FAQ about cycle tracks. You can read it here.

— Left turns and legal issues aren’t the only things people have had questions about. Other concerns I’ve heard from commenters are are how pedestrians will interact with the cycle track, how the City will handle right turns (a very big issue), and how bus stops figure into the equation. I’ll consider addressing those issues in a future story.