The St. Johns Bridge should have bike lanes. And it could have, if advocates nearly two decades ago chose to sue the Oregon Department of Transportation when the state agency completed a major renovation and failed to seize a golden opportunity to provide adequate bicycling access.

I recently spent time observing traffic on the bridge and came away even more shocked at how unacceptably inaccessible the bridge is for everyone not inside a car or truck. When I first shared images from that day over on Instagram, the response reminded me how many people share my concerns for what this bridge is like today, and my dreams for what it could become in the future.

Before I share some of those responses, let’s recall our history…

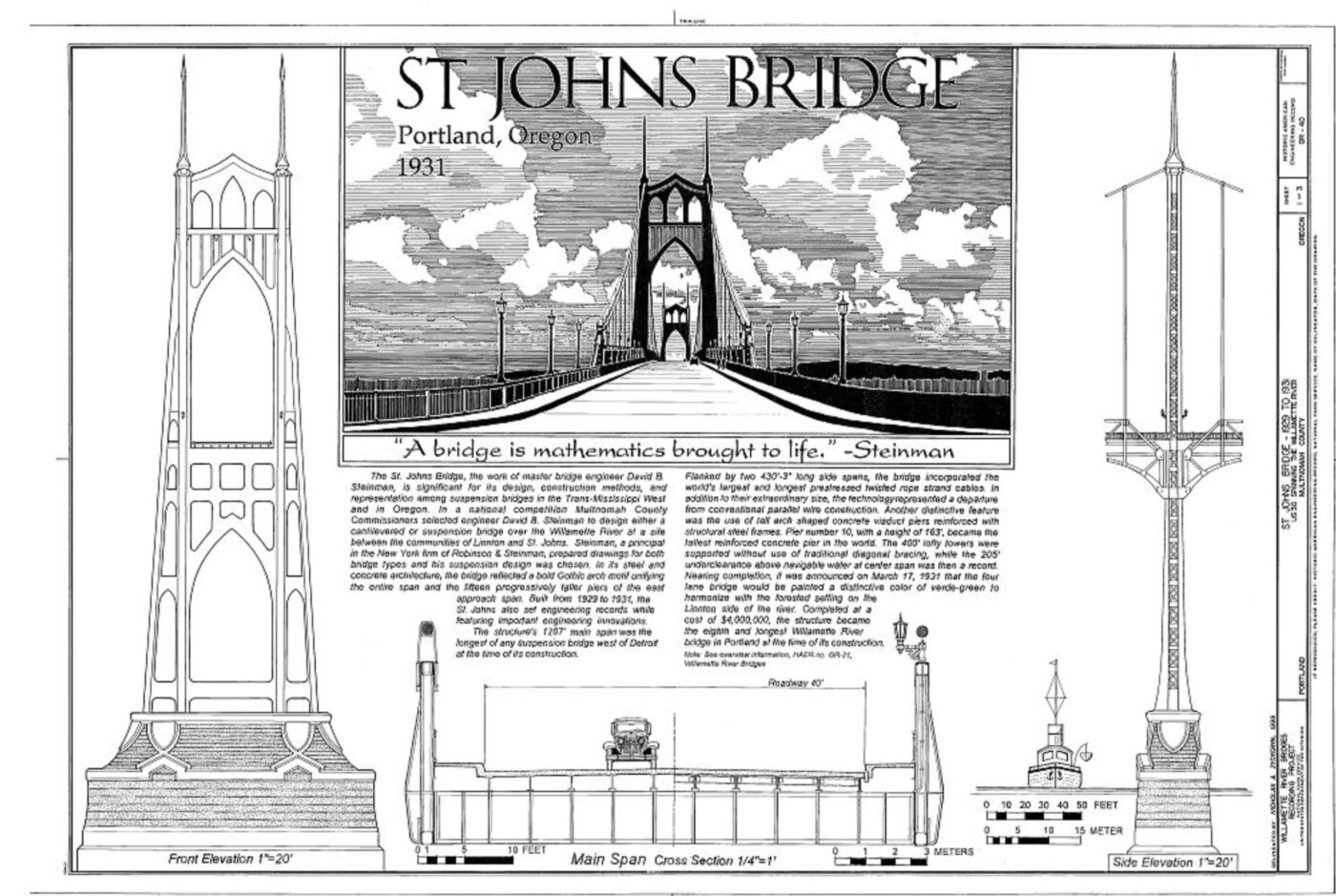

In 2003, ODOT began a major rehabilitation project. They spent $38 million to replace and repave the deck, repaint the towers, upgrade the lights and so on. But before ODOT re-striped the lanes with the same four lane, 40-foot wide cross-section the bridge had when it opened in 1931, they considered an alternative plan. ODOT put together an advisory committee (that included representatives from a bike advocacy group, TriMet, freight business owners, and so on) and commissioned a report from an engineering firm to analyze options and inform the decision.

In 2003, David Evans & Associates published that report. And guess what? They determined there would be, “No capacity constraints or operational flaws on the bridge that would prohibit the implementation of any of the striping options.” Central to this finding was that all roads that lead onto the bridge have just one lane in each direction and are controlled by traffic signals. Their analysis showed that while travel time across the bridge would increase (exact amount I’m not sure of), traffic would only slow and there would be no congestion on the deck.

But despite that study, despite clear concerns about safety and demands for bike lanes that bubbled up during the City of Portland’s 2004 St. Johns/Lombard Plan, and despite grumblings from the nonprofit Bicycle Transportation Alliance (now The Street Trust) and other bike advocates, ODOT caved to pressure from freight advocates and re-striped the deck exactly as it had been for the previous 74 years.

ODOT’s final decision on the striping plan came just one month after I started BikePortland, and I haven’t done the research to fully understand what happened. But I do know how it made me feel. My first post on the subject on May 12th, 2005 was published a few days after I heard the news and you can sense my anger from the get-go.

The Street Trust also objected to ODOT’s decision, saying in an op-ed published to their website that, “Under pressure from special interests, ODOT simply ignored the facts at hand. The result, if it is allowed to go forward, is a bridge that will continue to be unsafe for the quarter of the area’s residents who cannot drive.”

As made clear in my interview with former ODOT Director Matt Garrett in 2012 the agency “could have re-striped it,” were it not for the “force of the freight industry” that acted as a “cross-pressure” on their decision.

Portlanders tried to object. Letters were written to the Oregon Transportation Commission, there was even a naked bike ride protest, but ODOT ignored it all. They claimed a minor widening of the existing sidewalk and larger alcoves were “bike safety improvements,” but the truth was then — and remains today — that the sidewalk is not even technically wide enough for bicycle riders to share with walkers and riding a bike on the bridge is a harrowing experience.

ODOT installed sharrows seven years later. While I appreciate having my legal right to the road reinforced, those tiny patches of paint don’t do much for my blood pressure when drivers are bearing down on me at 35-plus mph.

When Mitch York was killed by Joel Schrantz in 2016, ODOT was asked to justify the lack of bike facilities on the bridge. An ODOT spokesperson had the audacity to claim in an interview with a local media outlet that they couldn’t install bike lanes because state guidelines require 19-foot wide lanes for freight trucks. That’s an outright lie used to justify a decision ODOT knows wasn’t based in fact or engineering best practices.

As made clear in my interview with former ODOT Director Matt Garrett in 2012 the agency “could have re-striped it,” were it not for the “force of the freight industry” that acted as a “cross-pressure” on their decision.

Garrett’s contrition validated for me why many of us felt The Street Trust should have sued ODOT for failure to comply with the Oregon Bicycle Bill that requires the agency to build adequate bike facilities whenever a road is reconstructed. I never learned exactly why they didn’t file that lawsuit, but I recall hearing there was some concern they might lose on a technicality and the precedent would end up weakening the Bike Bill in the future.

I can’t change the past, but I’ll never forget ODOT’s role in making us so unsafe on this bridge that I love and hate with equal passion.

And judging by responses to my photos on Instagram, that same ambivalence resides within many of you.

“Even with good skills and being comfortable at speed in traffic,” wrote Portlander Ira Ryan in an Instgram comment. “I still feel like each trip over the bridge could be my last… It only takes one glance at a phone by a driver to kill a human on a bike. Terrifying.”

Another commenter who walks across the bridge four times per week said, “I have long wished for a protected bike/ped lane on each side… I wait for a truck mirror to hit my head.”

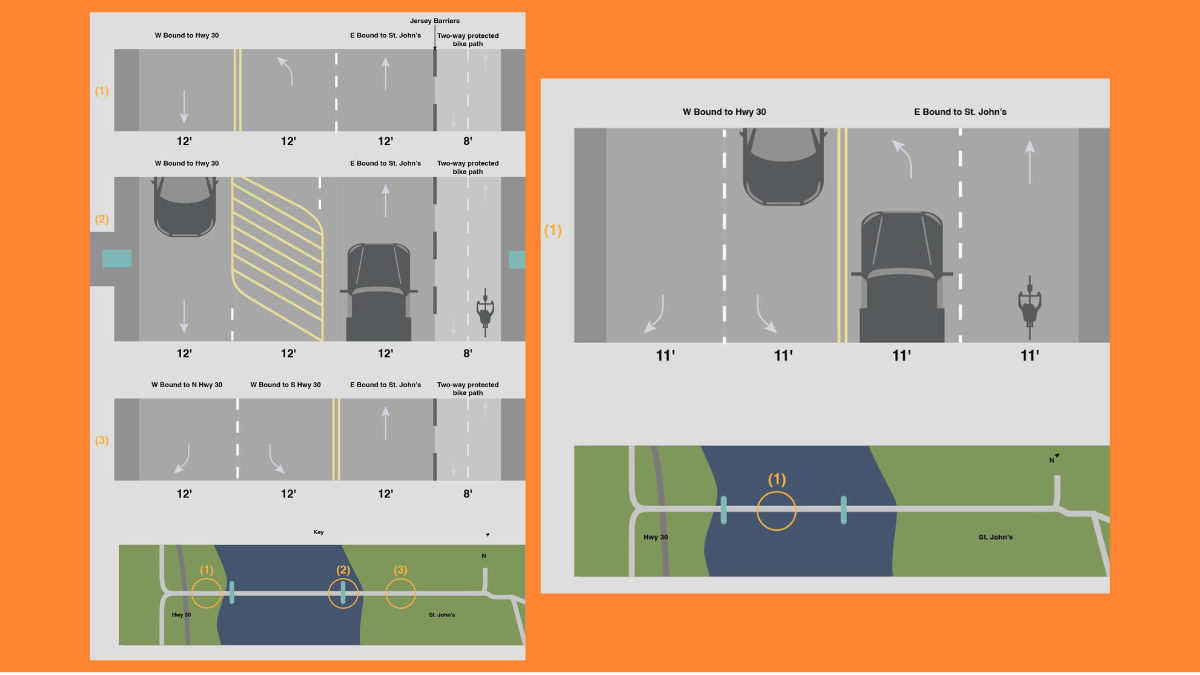

One reader, Ben Guernsey, even created a conceptual design of how he’d change the lane configuration to be safer for everyone.

While I think Ben’s idea should be given serious consideration, the ultimate solution is to get freight traffic off the bridge entirely. These large, loud, fume-laden trucks should have a bridge of their own so they aren’t routed through downtown St. Johns and dense residential areas. And that’s exactly what is recommended in ODOT’s Westside Multimodal Improvements Study that wrapped up late last year.

Whatever steps we take next can’t come soon enough. As these photos show, there’s clear demand by non-drivers to use our beautiful, iconic bridge without fearing for their lives, shouting to hear companions over the traffic noise, or breathing toxic exhaust. Surely we can re-imagine this bridge before the its centennial celebration in 2031.