Bike parking was the focus of our coverage Tuesday about the Portland City Council work session on housing production. But to me, the bigger transportation issue is how we pay for public infrastructure, things like bike lanes, sidewalks and sewers.

Commissioner Mingus Mapps initiated an exchange on this topic at the work session that deserves attention because it touches upon important issues Portland currently faces: how to pay for upgrading the backlog of inadequate transportation infrastructure in neighborhoods across the city — and how to stop adding to it.

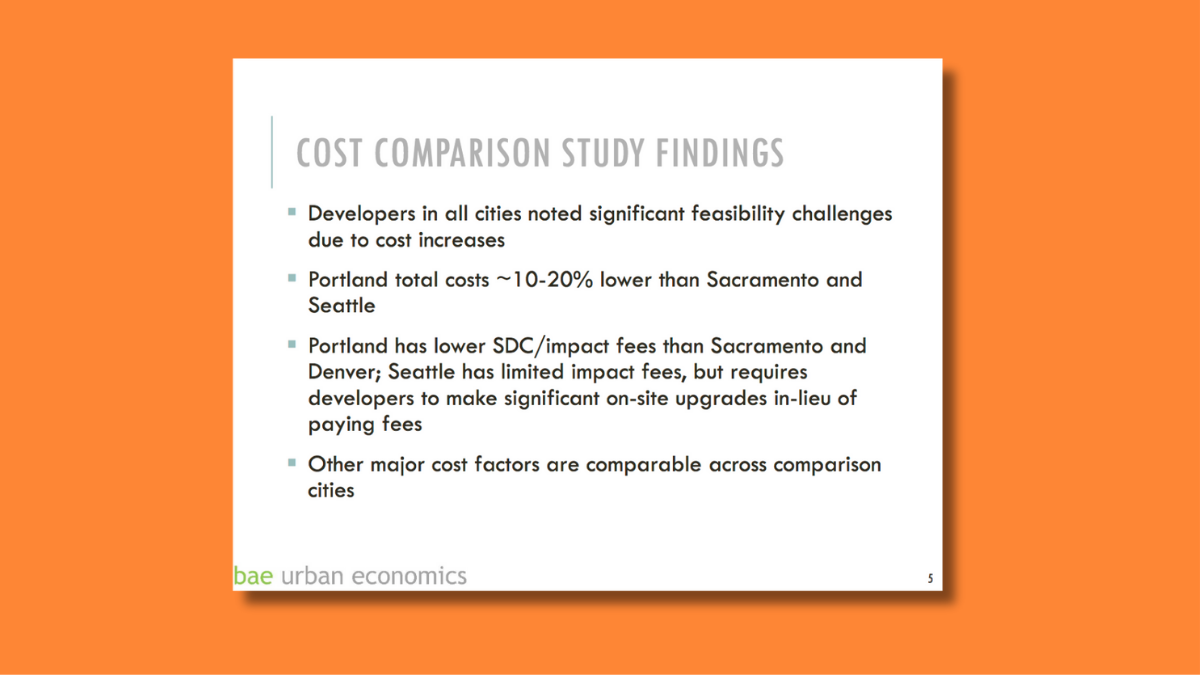

Mapps began by asking about city incentives for building affordable housing. In response, consultant Matt Fairris from BAE Urban Economics brought up allowing more exemptions from System Development Charges (SDC) as one incentive to build.

Mapps responded:

I’m your infrastructure guy on council, so I build water, sewer, roads, sidewalks, which we largely fund with SDCs. So there is this kind of puzzle, we can build a house but if that house doesn’t have a toilet that’s gonna be a problem. But I did notice in your data that Seattle didn’t have SDCs, although it was more expensive to build there.

Can you tell us how Seattle pays for roads, sidewalks and sewers?

Fairris replied:

The way that Seattle does SDCs and impact fees is they, instead of just charging the development community [a fee] … The City of Seattle pegs it to the development community and says, “we need a new street light, you have to build a new street light, developer.” We need new sewer infrastructure on this road, you developer have to do this as part of your cost … The cost to build, the “hard costs” are higher … because you are having to do some of this other infrastructure that, in the City of Portland, we charge SDCs and have the city tackle that.

And then Christina Ghan, who is the Policy Director on Commissioner Rubio’s staff and was facilitating the work session, stepped into the conversation:

Can I add one extra fine point on that—I came down to Portland from Seattle. Those improvements that Matt spoke to are all directly adjacent to the site, they are not located in the general vicinity, or elsewhere across town. They are hyper-localized costs that the developer pays for.

Mapps followed up:

Do they have an equity strategy? One of the things we try to do in Portland—historically Portland let’s say east of 82nd has been neglected in terms of investments of infrastructure, although it’s become much less true today. But one of the reasons it is much less true is that we use some of our SDC fees to build in underdeveloped parts of the city. Does Seattle have a strategy …

Ghan responded that Seattle relies on other financing tools.

Ghan’s point that Seattle’s developer improvements are adjacent to the site — i.e. “hyperlocal”— touches upon what has long been a sore point in Portland for both neighbors and developers.

Portland’s Transportation SDCs (TSDCs) do not have to be spent near the development. PBOT uses them as a revenue stream for projects across the city. This leads to a typical southwest Portland interaction in which a neighborhood association demands a sidewalk; the developer responds that they have paid tens of thousands of dollars in SDCs, and PBOT’s development review desk tells neighbors that the road doesn’t have the stormwater capacity needed to support a sidewalk — so pedestrian facilities go unbuilt.

A truism among southwest transportation advocates is that all SDC monies flow east. I have never repeated that in my three years at BikePortland, I’m not a forensic accountant and would never be able to verify it. But it was noteworthy that a city commissioner publicly mentioned SDC distribution. The rub is that southwest also has a stack of unmet infrastructure needs, in particular an absence of stormwater facilities and the resulting lack of sidewalks and sparse bicycle network.

[UPDATE 7/27/2023 – 11:15 AM: A reader brought to our attention the 2021 TSDC Annual Report which contains information about TSDC revenues and expenditures, and segregates the money flow by district. It appears that the inner east districts have the biggest gap between TSDC collected and spent, as of 2020-21 for the current cycle beginning in 2017.]

The exchange between Mapps, Fairris and Ghan suggests that there might be a more efficient way of meeting equity and transportation goals. The uncertainties, conflict and suspicions created with project-by-project charges might cost the city more than it realizes.

The comparable cities analysis between Portland, Denver, Seattle and Sacramento can be found in the study BAE Urban Economics did for the City of Portland.

Video of the work session is here.

Reports referenced in the session are available at Commissioner Rubio’s website.