On Monday, a Multnomah County jury awarded $1.05 million to a Tigard resident who was hit by a bus operator while riding his bicycle on Highway 99.

It’s a victory, but a reminder that bicycle riders and their advocates still face an uphill battle when it comes to establishing a legal right to the road.

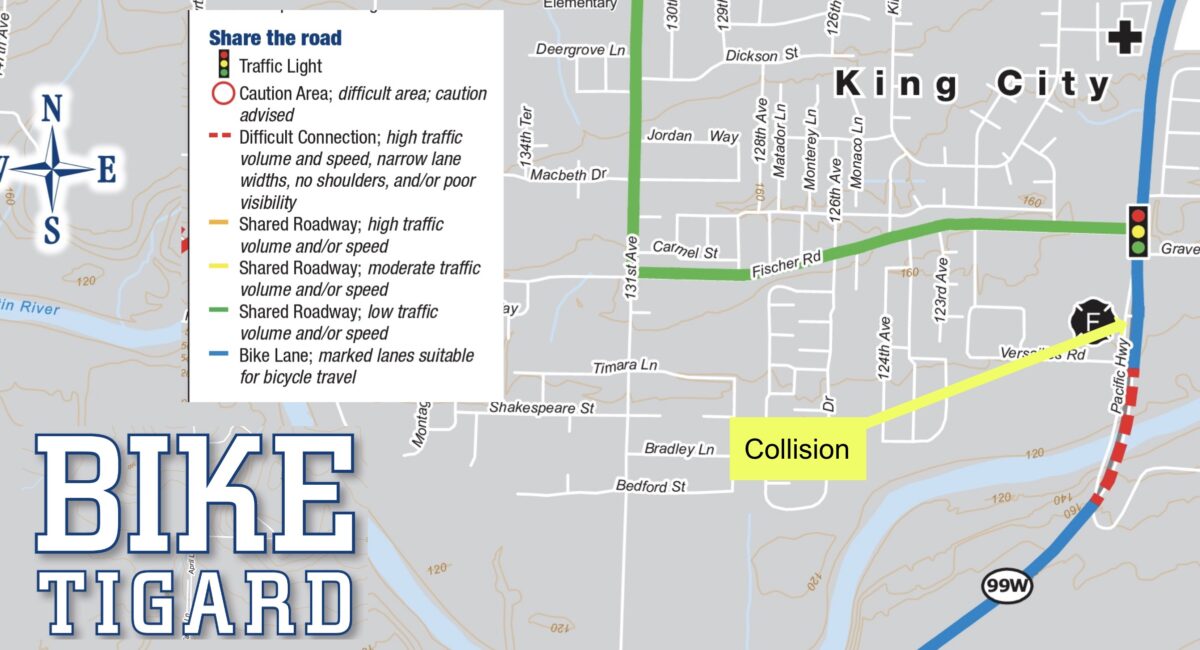

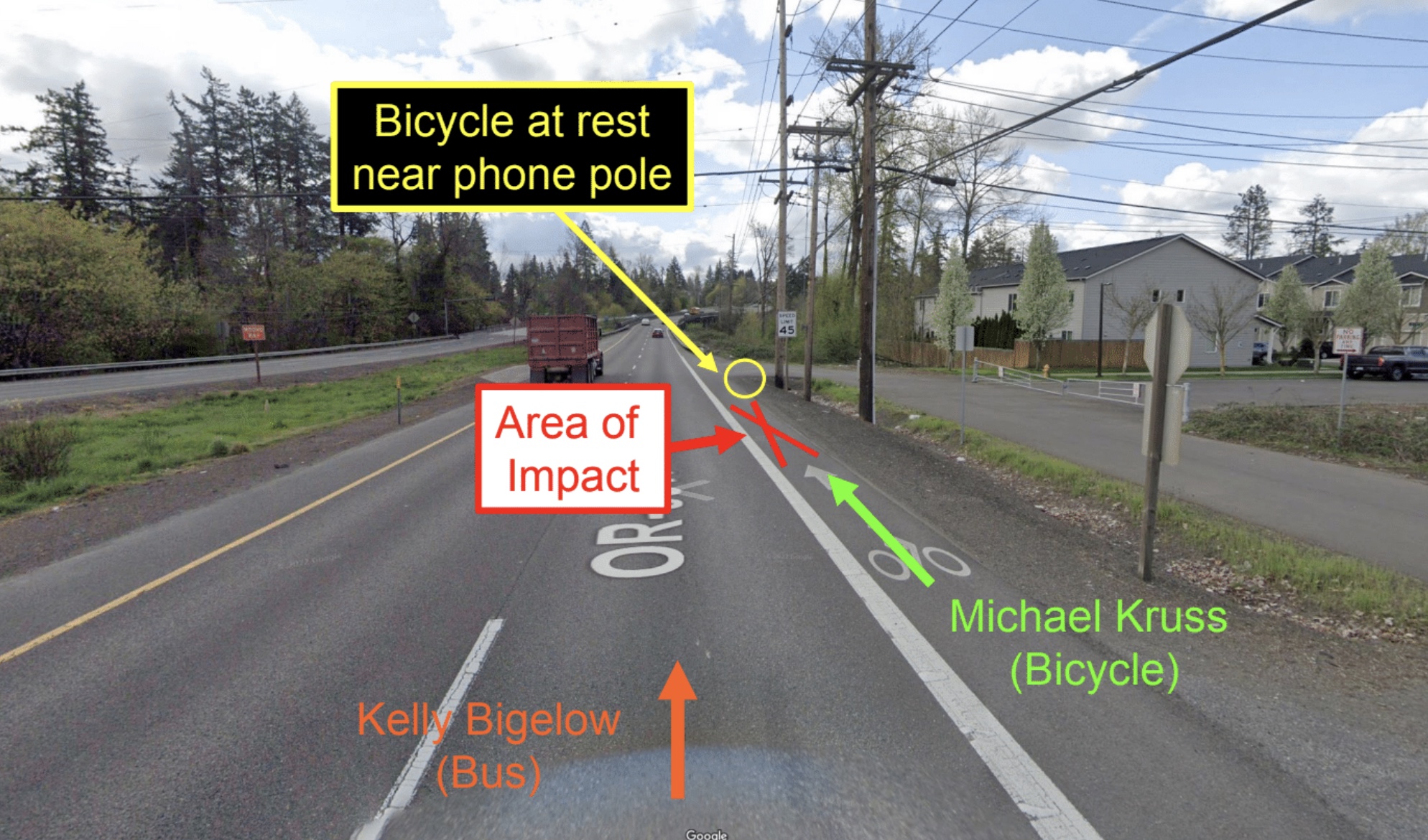

The collision happened on October 7th just before 9:00 am. 62-year-old Tigard resident Michael Kruss was riding his bike southbound in the bike lane of Highway 99. As he passed SW Versailles Road and saw a bridge over the Tualatin River (Google Map) coming up, Kruss had a choice to make — because the bike lane on this State of Oregon-owned facility abruptly ended about 100 feet in front of him.

We all know the feeling: Do you stay in the main roadway and risk being closer to other traffic? Or do you take a gamble on a sidewalk behind the guardrail that is full of debris, vegetation, and who knows what else? In this case, Kruss, a former All-American swimmer, chose to stay in the lane.

While Kruss continued south, the driver of a Yamhill County Transit bus, Kelly Bigelow, drove up behind him. According to a driver statement showed during the six-day trial, Bigelow saw Kruss in the bike lane. But the driver claimed that Kruss was “wobbling” in the bike lane and was riding “on or near” the white stripe of paint that separates the lanes.

“The driver stated he slowed because of the rider’s behaviors,” reads the driver statement recorded by First Transit, the private company that runs Yamhill’s transit system. “[Bigelow] looked up to check traffic in front of him and his distance from the bridge. While his attention was diverted from the bike rider, he heard a thud on the side of the bus.”

That “thud” was Kruss being hit and then slammed to the ground. The impact resulted in major injuries including a broken clavicle and scapula that required immediate surgery. Kruss also suffered a sternal fracture, nine broken ribs, and several serious contusions. He spent 17 days in the hospital, had three surgeries, and racked up over $318,000 in medical bills.

Adding insult to injury was the fact that lawyers for First Transit denied that it even happened and blamed Kruss for the collision. If not for Kruss’s legal team, led by Scott Kocher of Forum Law Group (a BikePortland financial supporter and contributor), we might never know the truth.

Forum Law Group filed suit against Bigelow and First Transit. Their complaint claimed that the driver’s actions led to Kruss’s injuries and that First Transit failed to adequately train and supervise their employee.

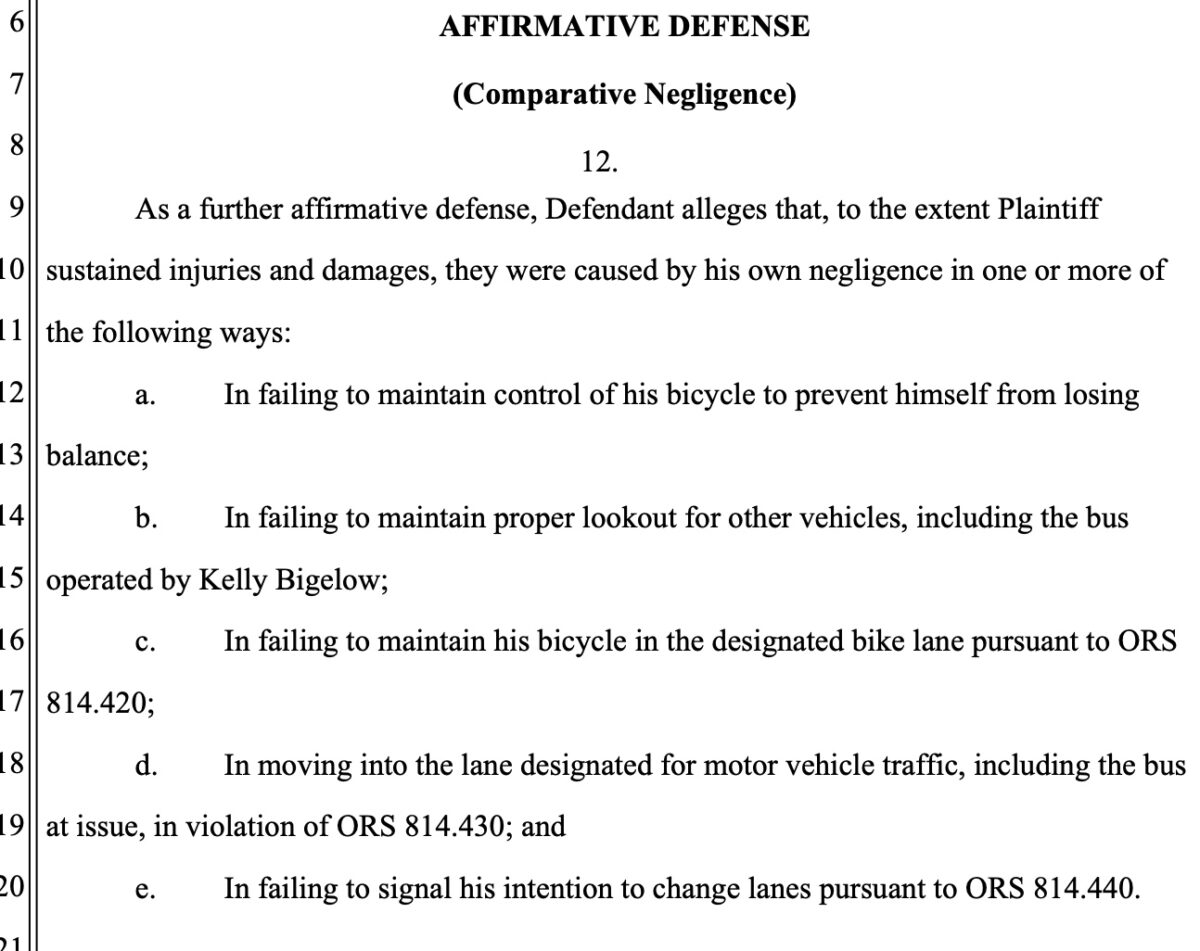

First Transit denied the allegations. The injuries and damages to Kruss, “Were caused by his own negligence,” stated a filing by First Transit’s lawyers, Bullivant Houser Bailey. They claimed it was Kruss who lost balance on his own, failed to see the bus (which was behind him), didn’t stay in the bike lane, and so on.

First Transit hired an expert witness, a retired leader of the Portland Police Bureau traffic crash reconstruction team, to back up their claims that Kruss wasn’t struck by Bigelow’s bus.

A key piece of evidence in the case was a black smear mark on the bus. Even though the mark was consistent with the height and composition of the rubber on Kruss’s handlebar grip, First Transit’s expert witness tried to deny it. It was only from Kocher’s cross-examination of the retired PPB officer that the truth came out.

Kocher and his team were also able to demonstrate to the jury that First Transit’s training requires bus operators give four feet of space to bicycle riders when they pass. Throughout the trial, First Transit acknowledged zero responsibility for what happened.

The design of the roadway was also a factor (the official Tigard Bike Map lists this section of the highway as a “difficult connection”) in the collision. Not only is this a 45 mph speed limit state highway with an unprotected bike lane, but as you can see in the images, the bike lane striping narrows from the standard eight-inch width to just four inches prior to the bridge (the legal width of a shoulder). This is a frustratingly common ODOT treatment that disrespects the rights and safety of bicycle riders and forces them into a precarious position. ODOT also failed to maintain a potential alternate route on the other side of the guardrail.

Even with the clear negligence of ODOT’s infrastructure, Kocher didn’t make them part of this case given the presence of strong “discretionary immunity” laws and other complications. Kocher felt his case was strong enough to win without getting mired in the mud with the State of Oregon.

Kocher felt it was entirely reasonable for Kruss to establish his presence on the white line prior to the bridge because he had made up his mind to share the lane. It was safer for Kruss to begin to move to the left of the shoulder well before the bridge so that he wouldn’t make a last second swerve where the road narrows at the guardrail.

Given the width of the roadway and the requirement of a four-foot passing distance, the safe move for the bus operator would have been to slow and wait behind Kruss until the road widened again after the bridge. But the bus operator (who died from Covid before he could be deposed or participate in the trial), chose to make the unsafe pass.

After hearing the facts of the case and listening to arguments from both sides, the jury sided with Kruss. But while they awarded him $1.295 million for economic damages and $318,000 for medical costs, they also said Kruss shared 35% of the fault. That dropped his award to $1.05 million.

Kruss had a rear taillight and was riding in a legal position on a road in dry, daylight conditions. The fact that he was found to share any fault in this collision is very unfortunate.

“This case proves two things,” Kocher told me. “First, the justice system is not broken. This is a success. Is the system perfect? No, but for everyone that says there’s no justice, that’s not true.”

“And second,” he continued. “Even in 2022 we still have a long way to go to fight for our right to the road.”