Our city hamstrings itself by putting city commissioners — who possibly have no management experience, background or interest in a bureau — in charge of running them.

Portland took another step toward good governance with the recent Charter Commission vote to advance their reforms to the November ballot. This City Council appointed, 20-member group of volunteers has been grappling for a year and a half with how to improve the way we run our city, this vote was a milestone in their efforts.

With their recommended changes to Portland’s charter more formalized, I decided it was time to become better informed about the issue.

With an open but skeptical mind, I plunged into the Commission’s materials. It only took a few hours for me to realize that I wasn’t bringing a very big pole to this pond.

How to design fair elections is a well-studied field and there is a lot of expertise involved, much of it technical. Probably the most useful thing I can do for the BikePortland reader is to summarize and link to the sources that most helped me become “informed enough” about charter reform.

So on that note, what follows is a link-rich synopsis of my path to charter enlightenment.

The Big Picture

Portland has had a “commission” form of government for over a century. It is an antiquated system in which each commissioner, in addition to their roles of passing ordinances and responding to constituents, oversees a portfolio of bureaus. In other words, commissioners have both policy and executive roles. This type of governance was long ago abandoned by other major US cities, with Portland being the last hold-out.

Currently, we elect four “at-large” commissioners and a mayor using a winner-take-all system. Voters get to choose candidates in all four races and are not restricted by having to live in a particular district. The candidate who receives the majority of the vote wins the seat, although this may take two rounds of voting, a primary and a run-off.

Oregon Public Broadcasting published a helpful article by Rebecca Ellis which describes our current system and the proposed changes.

What the Charter Commission is proposing

The Commission has proposed three changes to the way we elect our Commissioners and run the city:

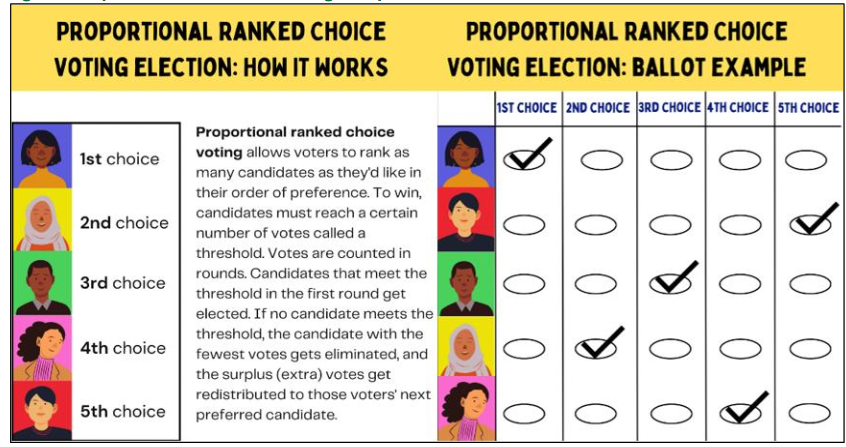

• Allowing voters to rank candidates in order of their preference, using ranked choice voting

• Four new geographic districts with three members elected to represent each district, expanding the city council to a total of 12 members

• A city council that focuses on setting policy and a mayor elected citywide to run the city’s day-to-day operations, with the help of a professional city administrator

They write that “it is the Commission’s belief and desire that this proposal will make Portland’s government more accountable, transparent, efficient and effective, responsive, and representative of every area of the city.”

The Charter Commission Progress Report #5 discusses the proposed changes in detail beginning on page 23. UPDATE (6/29/2022): Soon after our original preparation for this story, the Charter Commission released Progress Report #6 which is a summary designed “to give a high-level view of the approach and work of the Charter Commission at this stage in the process.”

How did they come up with that?

There are two main parts to the proposed changes: 1) moving management of the bureaus away from the commissioners and to the mayor/city manager and 2) changing the way Portlanders elect the City Council.

Concerning jettisoning the commission structure, the Charter Commission conducted discussions with bureau directors and elected officials, as well as 106 sessions with community groups and the public. There does not seem to be significant opposition to dropping the commission system from any quarter. On the contrary, the idea appears to have a lot of support. One vocal supporter, City Commissioner Mingus Mapps, said of the commission system, “It’s a crazy way to run a city, and it’s one of the reasons Portland underperforms on everything from homelessness to permits, time after time.”

The Progress Report summarized what Portlanders believe are the main weaknesses of our current way of doing things including: lack of accountability, failure to move forward on complicated issues, lack of coordination, silos, inconsistent and unqualified management, micromanaging, et cetera. It is a long list.

Portland’s homelessness crisis serves as a good example of this government dysfunction. Last week’s BikePortland Monday Roundup included an article about Houston’s success in addressing homelessness and their use of a “Housing First” model. They credited getting everyone “to row in unison”—the city and the non-profits—with their success.

But Portland’s more fundamental problem is getting the city bureaus to row in unison. As Mapps told KOIN 6 in March,

One of our challenges right now is to get different city bureaus to work together. I know Portlanders are furious with the state of houselessness out there, but one of the reasons why we struggle is that we have about five different bureaus that play a role in solving houselessness. It’s not just a matter of providing housing, houselessness is often a mental health issue, and a public safety issue. And if you’re camping in a park, it becomes a Parks issue, if you are camping on a sidewalk it becomes a PBOT issue.

One of the things we have failed to do over and over again is to get these different bureaus to work together to solve problems like getting people off the streets to safe, supportive housing. You see the results of what the status quo does. If we move toward a coordinated system run by professionals, I believe we would do much better.

To sum up, our city hamstrings itself by putting city commissioners — who possibly have no management experience, background or interest in a bureau — in charge of running them.

The problem with Portland voting

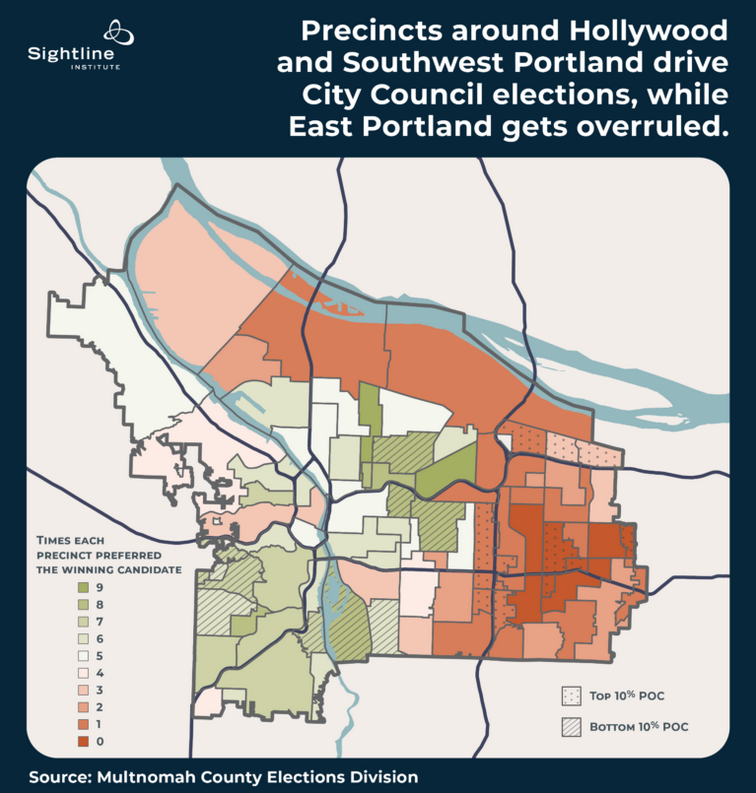

I didn’t realize we had a big problem until I read a series of outstanding articles by Kristin Eberhard for The Sightline Institute. If you only have time to read one piece I’ve linked to in this post, I recommend Want to Give Portlanders of Color a Voice on City Council? Districts Won’t Help.

Eberhard makes a strong case for proportional ranked-choice voting and brings to life the analysis that the MGGG Redistricting Lab at Tufts University did of Portland voting.

It is the MGGG (Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group) mathematical models of how various voting schema would play out in Portland that informed the Charter Commission’s recommendation of ranked choice voting for multi-member districts. And although MGGG used race as their model for underrepresented voters, Eberhard points out that “the results apply to Portlanders who are in the minority for any number of reasons: small business owners, people who are dependent on transit, those who get around by bike, youth, or parents of school-age children.”

The Charter Commission concluded that four multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting will bring fairer and fuller representation to city government, could improve participation, and also promote more issue-oriented, civil campaigns with less negative campaigning.

But it wasn’t a unanimous vote. One of the three commissioners who voted against the reforms was recent city council candidate Vadim Mozyrsky. Similarly, City Commissioner Mingus Mapps has not taken a strong public position in support or in opposition to the whole package, although in an April interview with the Rose City Reform substack he expressed doubts about some aspects of it. So there are dissenting voices, but it is probably too early to detect an organized opposition. The Charter Commission work sessions were taped, and around 1:18:00 of the June 6th meeting, you can listen to the comments of two dissenting commissioners, as well as an impassioned rebuttal by the committee co-chair.

The takeaway

The four-district, multi-member proposal combines elements of both geographical representation and of fairer representation of non-geographically defined minority concerns. The tension between geography (with neighborhood associations often being the stand-in representative) and minority interests (such as better bicycle infrastructure) underlies many of Portland’s political skirmishes. The changes the Charter Commission recommends could result in a more productive political dynamic with more non-majority concerns achieving a voice on the city council.

UPDATE (6/29/2022): Yesterday the Willamette Week reported that two newly-forming PACs (political action committees) will be taking opposing sides on charter reform. Vadim Mozyrsky has recruited Chuck Duffy and Steve Moskowitz (two former Bud Clark aides) to his yet-to-be-named PAC which will oppose the package of reforms advanced by the Charter Commission, and Building Power for Communities of Color is starting a PAC to support the reforms. Mingus Mapps’s existing Ulysses PAC will most likely be hosting “educational forums” about the reforms, as a softer way of pushing back against the bundled changes. Mapps and Mozyrski favor adopting a mayor-manager system but are against aspects of the other commission-proposed reforms.