“Some of the housing advocates have realized that without the transportation piece, they’re not going to be successful.”

— Amy Stelly, Claiborne Avenue Alliance

For many BikePortlanders, the connection between housing policy and cycling is self-evident: Denser places mean shorter, more bikeable trips, which sets off a cascade of positive impacts that includes everything from saving money and better health, to a cleaner and cooler planet.

What might not be as obvious is the extent to which our systemic infatuation with driving cars has created density’s opposite: sprawl.

One of our main takeaways from day one of the YIMBYtown conference that kicked off at Portland State University this morning is how closely connected the pro-housing movement is to the burgeoning war on cars movement.

Amy Stelly is a freeway fighter who lives near Interstate 10 in New Orleans. At oane panel today she shared how she never planned to become a transportation and housing advocate, but she was pulled into the work as she began to see the way the mere presence of this car-centric infrastructure had on her community. The freeway impacted everything from peoples’ ability to get respect from bankers and politicians, or even to just get to their jobs without a car.

Advertisement

“I think some of the housing advocates have realized that without the transportation piece, they’re not going to be successful,” she said at a lunchtime panel titled, “Housing Abundance Requires Abundant Transportation.”

“If we don’t take that land for the common good as opposed for car infrastructure, then nothing is ever going to change.”

— Alex Contreras, Happy City Coalition

“Folks in New Orleans think now that if you ride the bus, then you’re poor, you’re less than,” Stelly shared. “That isn’t good for people who are forced to ride the bus because they are stigmatized, particularly women of color, who are being pushed out more and more into the suburbs, where the transit between that housing stock and the city is really, really bad.”

A fellow freeway fighter from the Los Angeles-area suburb of Downey, Alex Contreras with Happy City Coalition, knows about these impacts all too well. Asked to share their lightbulb moment as an activist, they said, “If we build nothing but sprawl and there’s nothing but cars and we don’t take that land for the common good as opposed for car infrastructure, then nothing is ever going to change.”

The conference became even more antithetical to the overuse of cars in a later panel. Even though the title was about land use, climate and housing policy, we were pleasantly surprised to hear nearly complete unison that car-centric planning and thinking is the largest culprit to many of the messes we currently find ourselves in.

“It’s very difficult to call yourself an environmentalist if you’re still promoting and supporting auto-centric development patterns and transportation policies.” That’s how Ben Holland with the Rocky Mountain Institute explained what he believes is an overemphasis on electric cars as a solution to our urban issues even among many progressive leaders.

Advertisement

Holland was joined by Portland-based urban economist and City Observatory founder Joe Cortright and Jarred Johnson, the chief operating officer and development director of Transit Matters, who beamed into the panel from Boston.

Cortright’s first slide included just three words: “Cars kill cities.”

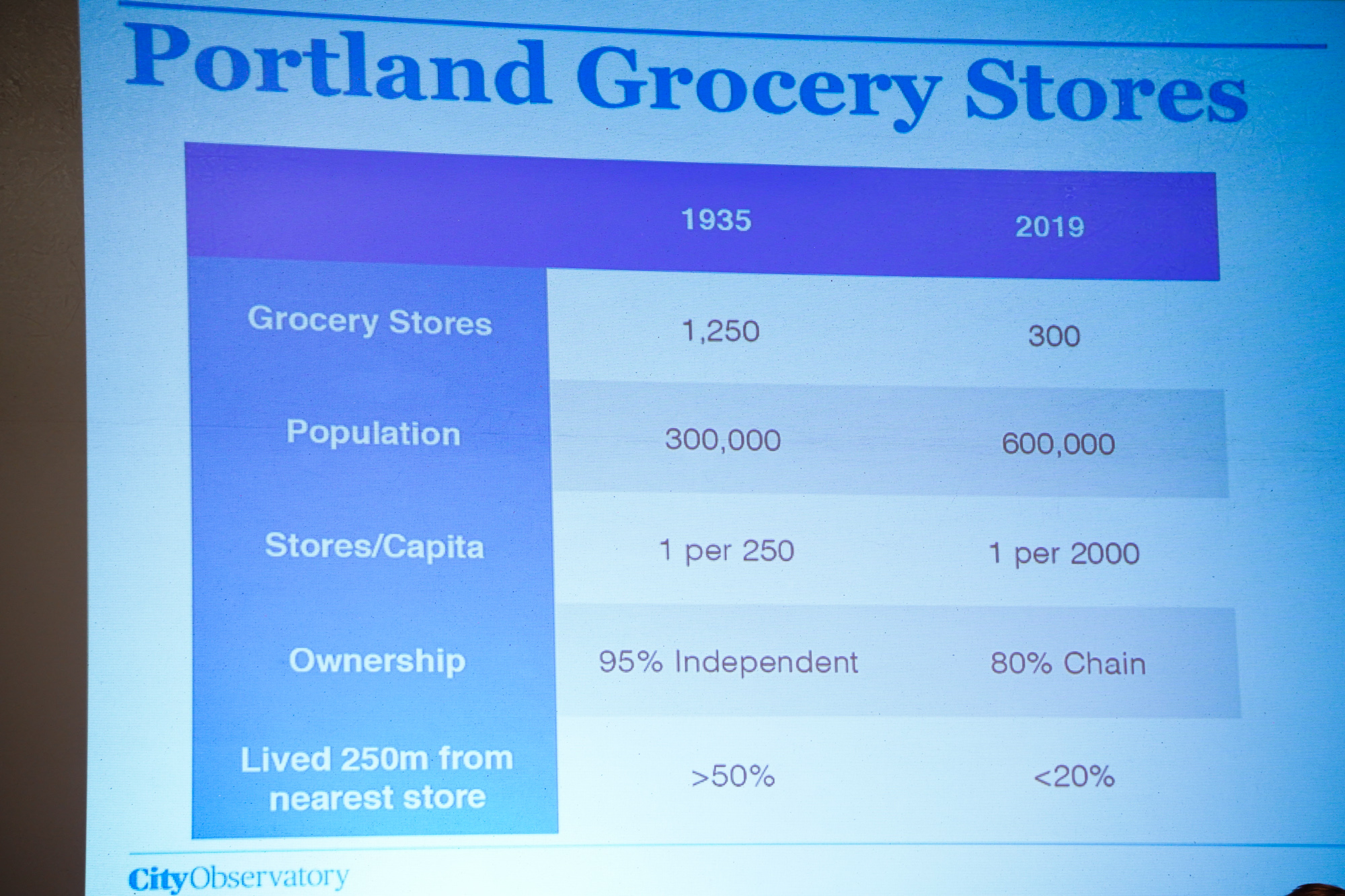

To demonstrate this fact, Cortright presented data that blamed cheap, subsidized cars for a devastating decrease in grocery stores in Portland. Between 1935 and 2019, Portland lost 75% of its food retailers. This in turn led to food deserts, more carbon emissions, and so on. Today, Cortright estimates Americans drive an estimated 120 billion miles to get groceries each year, that’s about 4% of all travel in the country and it emits about 60 million tons of greenhouse gases.

Cortright said the loss of grocery stores within walking distance is a “cautionary tale” about how land use and transportation are intertwined. “Car dominance fundamentally changes the economics of the way we live in ways that preclude us from having the type of urbanism that we’d like to have.”

Advertisement

Despite the negative impacts that driving-centered urban form requires, many leading climate groups and ostensibly progressive policymakers still see cars as the future. They think replacing gasoline with electricity should be our top funding and political priority.

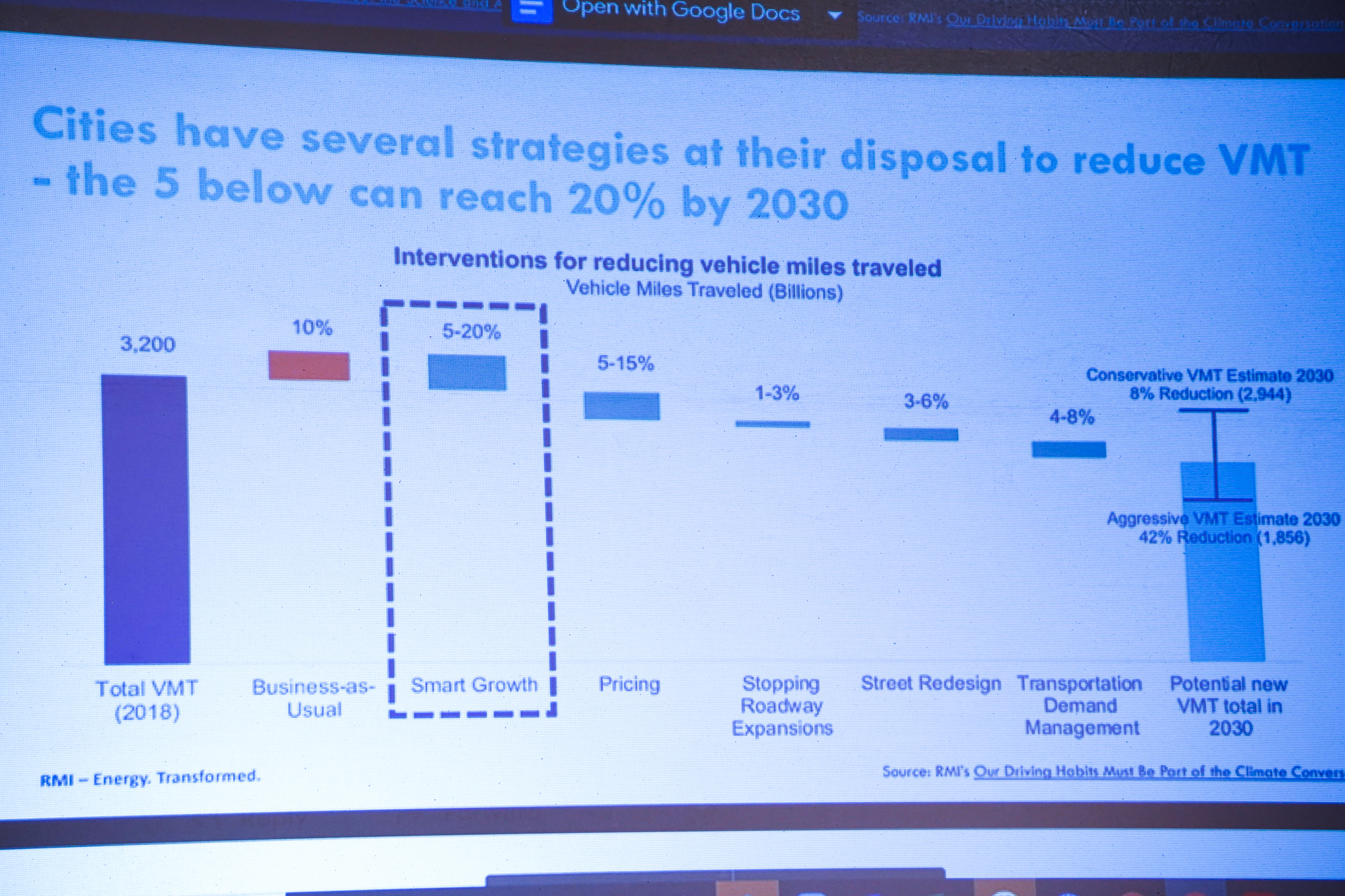

As a baseline for their research, Holland said they assumed for the U.S. to reach its climate goals we need to reduce transportation emissions by 45%, a figure that would require 70 million electric cars to be on the road by 2030. That’s a tall order since we have just 2 million on the road today. And even if we reached that many e-cars by 2030, VMT would need to be reduced by 20% per capita.

“I think e-bikes have potential to be a game changer. That’s the electric vehicle I’m really excited about.”

— Jarred Johnson, Transit Matters

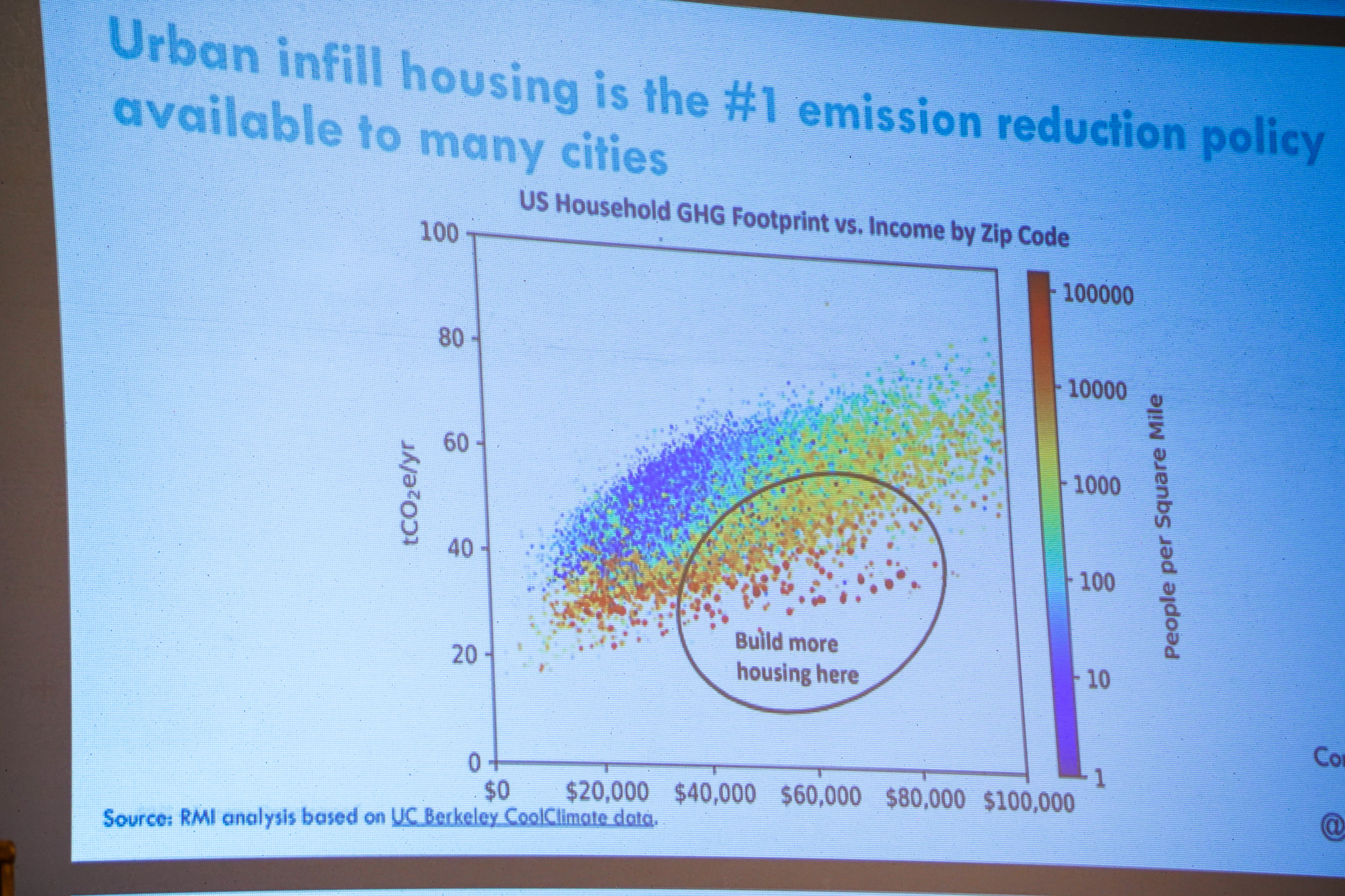

RMI then aligned all their research around what it would take to reach that level of VMT reduction. They found infill housing centered around non-car-centric smart growth policies (an umbrella term that includes congestion pricing, cycling and walking infrastructure, street design, transit, etc.).

Holland said a big reason many of the major players in the climate policy and environmental philanthropy world have mostly ignored these “non-electrification” strategies because they lack numbers or data to back them up. “So what you see is a classic situation where we’re falling back on assuming some level of adoption of electric vehicles to achieve these [greenhouse gas reduction] goals.”

For Johnson, there’s one type of EV he’s “really excited about.” Electric bicycles. He feels e-cars will play a key role in climate adaption, but, “A car is still a car and it still has some of those major drawbacks when it comes to housing… And we really have to look at the impact of a policy that leans far too heavily on that.”

“I think e-bikes have potential to be a game changer,” Johnson continued. “That’s the electric vehicle I’m really excited about.”

(YIMBYtown continues Tuesday with a full slate of panels and workshops. Learn more at the conference website.)