(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

As much as the coronavirus scares me, the long-term implications for transportation frighten me more.

— By Contributor Catie Gould

The last time I took public transit was the last day of my pre-coronavirus life.

On March 10th I took the MAX downtown for a meeting. Afterwards I had a couple beers with friends, and sometime between ten and eleven I re-boarded the MAX to go home. At the platform a man struck up a conversation and talked with me all the way to my stop. He claimed he had recently been in Seattle where he’d been infected by and recovered from Covid-19. He said he felt fine now, but I noticed his cough. I made a beeline for the shower as soon as I got home.

In retelling this story to family and friends, one question kept coming up: What was I doing on public transit in the first place?

As much as the coronavirus scares me, the long-term implications for transportation frighten me more. We have two major issues ahead of us: How do we keep transit operators and passengers safe, and what do we do if most people never come back to transit at all?

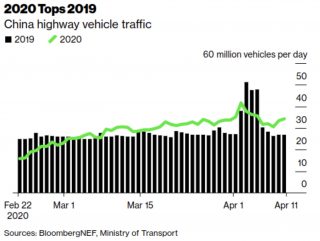

Early indicators from China are not promising

China is way ahead of us in returning to “normal” and as of March, traffic volumes there have rebounded to higher levels than the previous year.

While it appears that people are still not traveling for holidays, on April 11th highways carried 27% more vehicles than the year before.

A study of subway systems in seven Chinese cities published in mid-March reported that of people using the subway and public transportation before the pandemic, only 34% had resumed doing so while 40% switched to motor vehicles (private cars, taxis, and online car bookings) to travel. In Hangzhou, a provincial capital city of 10 Million people, a survey at the end of March found the municipal bus system had recovered 50%-60% of regular ridership.

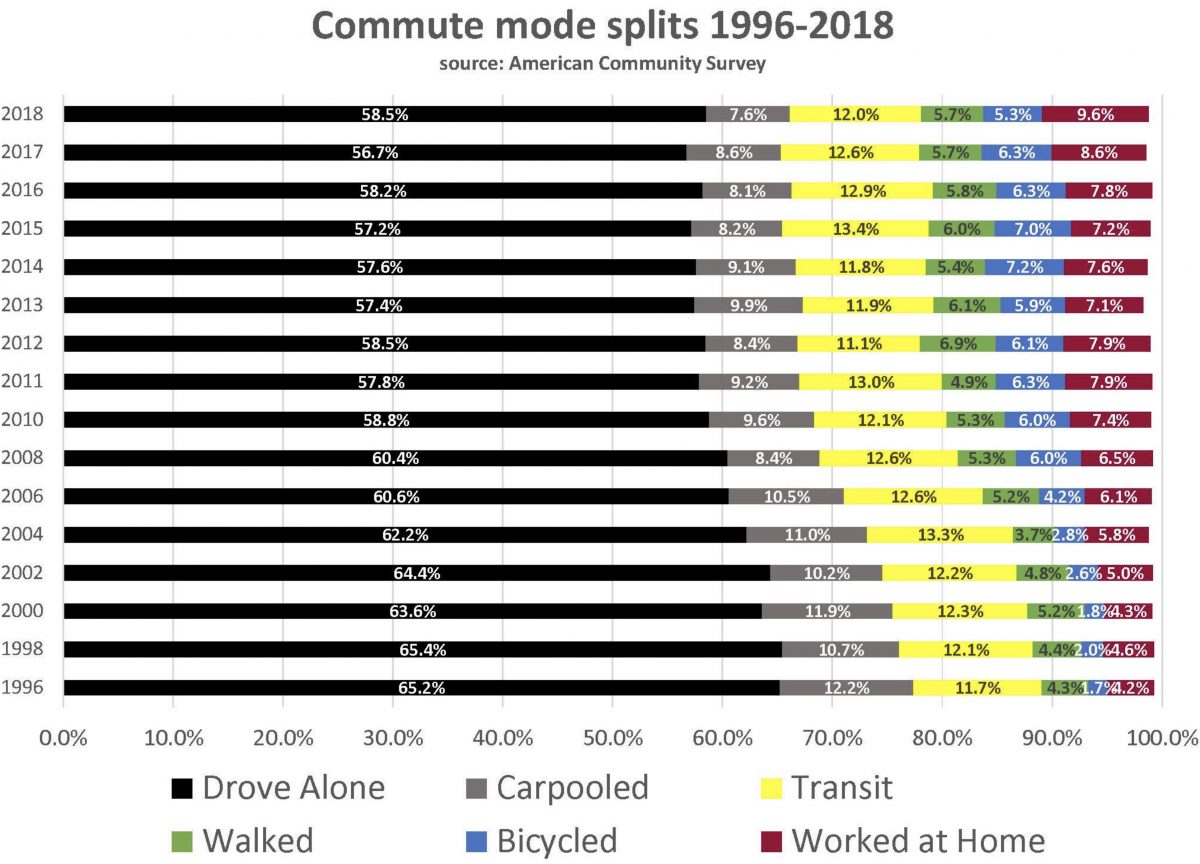

While it’s too early to tell if these trends will be consistent across countries, the implications of a similar mode shift in Portland would be staggering. In 2018 43,800 Portland residents — or about 12% of all commuters — took public transit as their primary mode according to the American Community Survey. If 40% of them switched to taking cars, that would be an increase of 17,520 additional car commutes. That would be the largest one year increase in car commuting since 1990 and 50% higher than the previous record set in 2018. (This is perhaps an optimistic view that everyone will eventually have a workplace to go back to, and the economy quickly rebounds into its pre-pandemic roar.)

Regardless of exactly where we land, the flight from public transit will be significant and we need to plan for it.

Catch the bus, not the virus

Concerns about catching the virus on transit are very real.

In New York City, transit operators have died at higher rates than police and firefighters combined. By May 1st, deaths had tripled to 98 Metropolitan Transit Authority employees. Out of 78,000 employees 2,000 have tested positive and more than 4,000 are quarantined at home. Transit operators, like the passengers they serve, are more likely to be from minority populations who are disproportionately killed by the virus.

Even Jeffrey Tumlin, a hero on transportation twitter and new Director of San Francisco Muni, urged people to stay off public transit. In early April he temporarily suspended 70 bus lines, allowing 40% of the workforce to stay home in early April. Some lines have returned since, but a 30-cent fare hike was also approved to go into effect in July in an effort to balance a sinking budget.

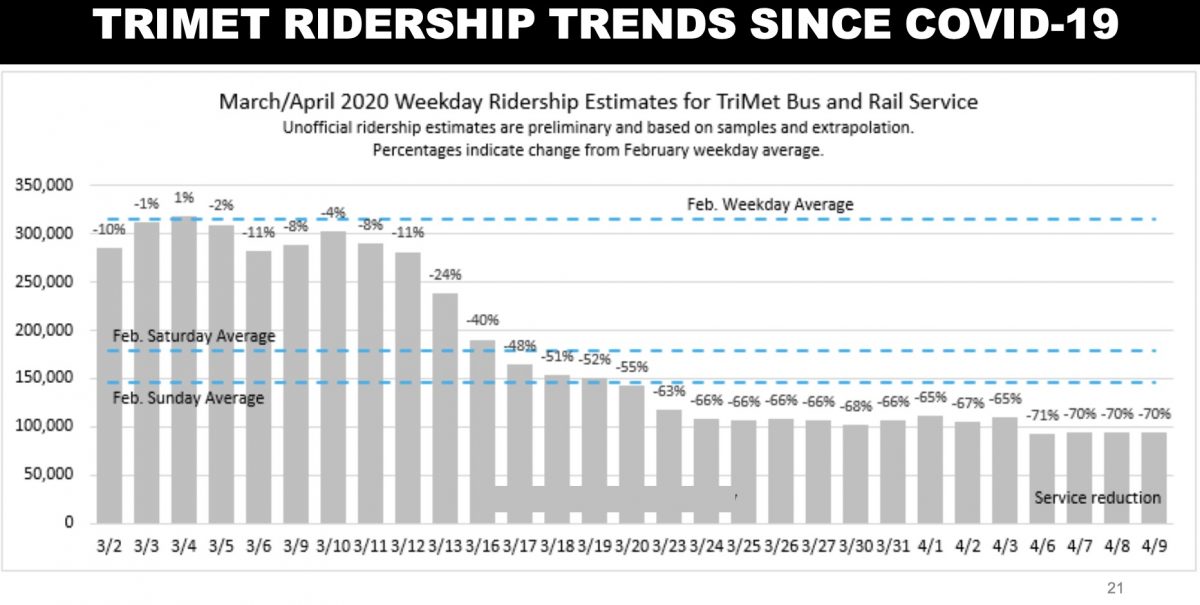

At home in Portland, Trimet has been criticized by its union for its slow speed in distributing protective equipment and adequate sanitizer to drivers. On April 5th they limited buses to a maximum capacity of 10-15 people and cut service on many lines. Boardings have dropped roughly 70% since February.

Transit’s white flight

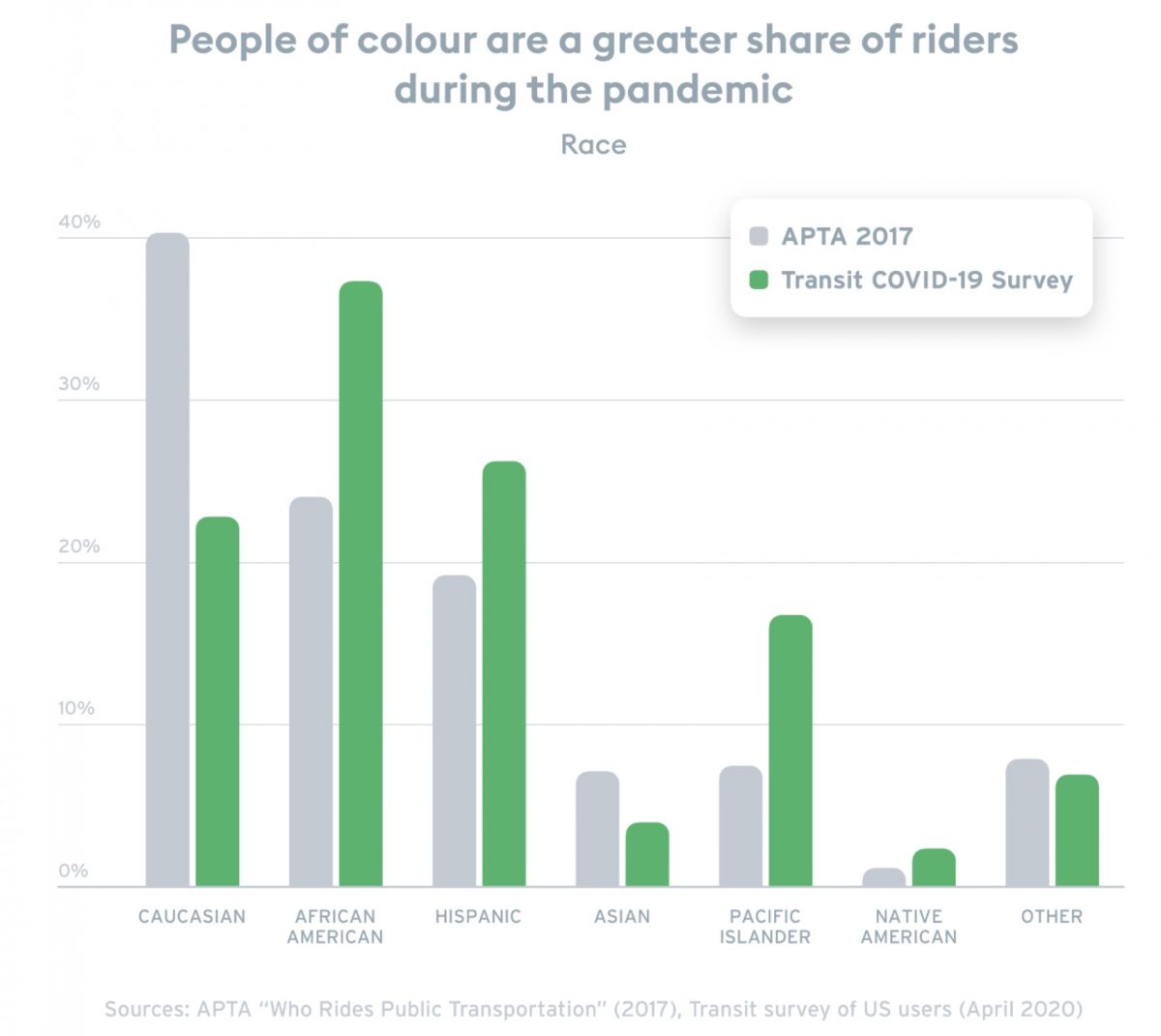

A survey by Transit App, shows that in the US the flight from public transit has been disproportionately white, male, and affluent. Of those left riding transit 92% are essential workers, 70% make less than $50,000 per year, and 85% do not have a car at home and do not have access to one.

Here’s how Transit App summarized the survey:

“… the amount of ‘white flight’ risks making public transit more marginalized than it already is. When things settle down, and when more people begin to return to public transit, we’re all going to have to ask ourselves some tough questions about how our transportation dollars are allocated. Our society’s dependence on good public transit has never been so obvious.”

Fighting the car culture war

“Many… are buying cars to reduce their use of public transit or shared transportation to avoid the chance of contracting the virus.”

— AutoNation CEO in the New York Times

While transit agencies make painful cuts and struggle with infection control, automakers are likely hard at work developing ad campaigns that cling onto some peoples’ feeling that cars are the safest way to travel. According to a recent survey by Cars.com, 20% of people searching for a car said they don’t own one and had been using public transit or ride hailing.

To combat the marketing onslaught, people will need good and safe options. TriMet will need to invest heavily and publicly in infection control like accelerating installation of protective barriers for drivers, reprogramming rear doors to open for boarding, and eliminating fare inspections. New strategies like temperature checks or voluntary location tracing apps to aid contact tracers might become necessary to prevent a new surge of cases as some industries head back to work this summer.

One thing is clear; as car users return, they’ll bring a trail of destruction in their wake, further affecting public health with their toxic emissions, violent crashes and other negative externalities we’ve enjoyed a slight reprieve from.

Even if people get back on transit, challenges remain

Even if Portlanders do flock back to transit, there might not be room for them. Buses that could previously carry up to sixty passengers are now capped at fifteen. According to TriMet spokesperson Roberta Altstadt, unless the Oregon Health Authority changes its physical distancing guidelines, those restrictions are here to stay. TriMet is planning for multiple re-opening scenarios, but adding capacity back to the system through schedule changes alone will be difficult.

New and improved bike lanes and the impending rollout of dockless e-bikes this summer could fill the transportation gap, provided that the Portland Bureau of Transportation can work one step ahead of a large-scale re-opening. The Slow Streets Safe Streets initiative is one small step in that direction.

As local leaders move mountains of funding into economic recovery, preventing gridlock and a flight from transit could be a uniting goal. To be successful, decision makers must center the needs of transit dependent workers and prioritize active transportation with an urgency, vision and tenacity we have yet to see. Time will tell if we moved fast and far enough.

Further reading: The Rebound — How Covid-19 could lead to worse traffic by Will Barbour on Medium (4/29/20)

— Catie Gould, @Citizen_Cate on Twitter

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.