(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Part of NW Portland Week.

Thurman Street is the last neighborhood north where you can find the sort of stuff that, for a lot of people, make Portland Portland.

One block north of the Food Front Cooperative Grocery and the gluten-free bakery Dessert Labs, you hit the Holiday Inn Express. Then come the railroad tracks, warehouses, gravel distributors, floodplains and eventually just trees to the end of the earth, or at least to Scappoose.

Walking down Thurman Street itself is so rewarding that one of Portland’s most famous residents wrote a whole book about it. They keep a copy behind the reference desk at the branch library on NW 23rd and Thurman: Blue Moon over Thurman Street, published in 1993 by the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin and the photographer Roger Dorband.

Le Guin (who’s now 86 and still lives off Thurman) recruited Dorband (then a Portlander, now based in Astoria) to walk Thurman with her in July 1985 and tell the stories of the street.

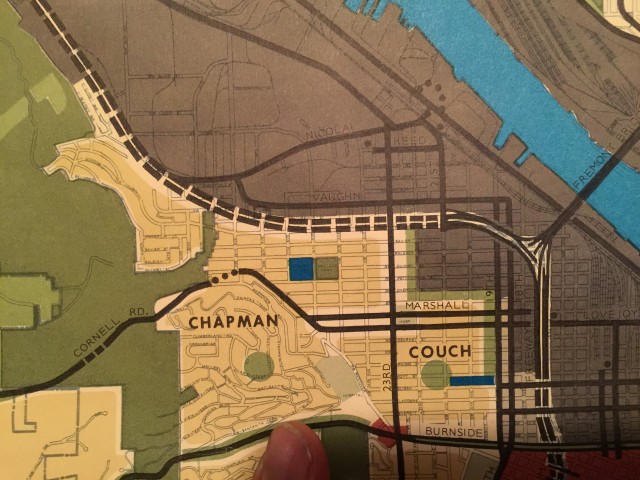

But the book, and Thurman Street itself, is all the more beautiful for a story that isn’t in it: Just like Division and Clinton streets in southeast Portland, it was supposed to be long gone by now. Thurman spent most of the 1970s scheduled to be purchased by the Oregon Department of Transportation and bulldozed to make way for what would have been Interstate 505, a 1.4-mile freeway spur that would have connected I-405 directly to St. Helens Road.

(Image via Kernal Moses)

Why did Thurman survive long enough for Le Guin and Dorband to memorialize it, and for Portlanders to park their bikes in the corral outside the Dragonfly Coffee House today? In part because of the mostly forgotten actions of two women 37 years ago.

One of them was Connie McCready, the last Republican to serve as mayor of Portland. The other was Marjie Lundell, a northwest Portlander working as one of McCready’s assistants when she was a city commissioner in 1979.

Thanks to the defunct website of the late Portland planner and historian Ernie Bonner, which you can still browse on Archive.org, we tracked down Lundell and spoke with her by phone on Thursday. Here’s a lightly edited version of what happened, in Lundell’s words, when the decision to condemn the land along Thurman and Savier streets for Interstate 505 came before Portland City Council.

I think it’s one of the best stories ever in City Hall.

I was living in an apartment in Northwest: 23rd and Glisan. The highway department had been saying for years that they were going to build that freeway. Nobody was doing everything to improve property because everybody knew there was going to be a freeway there. It’s social engineering at its scariest.

Connie was a very interesting person to work with. She was a reporter herself, so fair and balanced reporting was absolutely required. But you could pitch.

The council was split 3-1 in favor of the freeway, and Connie hadn’t announced a position. Lloyd Anderson was on the council; he was an engineer, and he was planning to vote yes. Connie really, really trusted his opinion.

It was the day of the vote, and they were to vote at 2 o’clock. And we would go out to lunch. So I just said, “Let’s take a tour of the Thurman-Vaughn corridor and have a look at the land you’re going to vote on.” So we drove Thurman. and Connie would say, “Oh look at that little Victorian house!” And I would go, “That would be part of the take.” And I had also arranged for lunch at a little Chinese restaurant in the industrial area. Because the idea was that we needed the freeway because it was so hard to get to the industrial area, and I wanted to show how easy it was to get there.

At lunch, I made my pitch the last time. And she said, “You know, everything you said makes sense to me, you may even be right, but Lloyd is going to vote yes.” So that was it.

Then the fortune cookies come, and Connie opens up this fortune cookie. And she looks up at me and says, “Oh my god, you are good.”

And I said, “What?”

She said “Look what it says!”

It said There is still time to choose an alternate path.

I didn’t have a thing to do with it. I just looked up and I said, “I tell you, it’s the right choice.”

When we got back to City Hall, it came in that Lloyd was going to change his vote to “no” on the freeway. She gave him the fortune cookie, and when he was explaining his vote he read it to the council.

It was a cliffhanger and people knew that she was the swing. When she announced her no vote, all the people from Northwest burst into applause.

If you go down to the Thurman-Vaughn corridor today and look east, it looks exactly like the architectural rendering back then said it would: apartment houses and little shops and people walking dogs. I eventually bought a house, and later I learned that the bank that my house sits on would have been the berm for the freeway going off into St. Helens.

But we stopped it.

A lot of the reporting we’ve done on northwest Portland this week has looked at ways the area is trying to reconnect the neighborhoods that were split by one fateful decision: the construction of Interstate 405. If it weren’t for the work of Portlanders like McCready and Lundell, among many others, we’d have a lot more problems to write about today.

Thanks for this post also go to Carl Larson, a longtime fan of NW Thurman who introduced me to Le Guin’s book, and to former Mayor Bud Clark, a northwest Portland resident who remembered part of the fortune cookie story and wrote to Bonner about it. Correction 4/17: An earlier version of this post omitted relevant details about Anderson’s vote, which also changed at the last minute.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today.